On the significance and meanings of Tower Hamlet Council recognising Cockney as a Community Language, as well as supporting the promotion of Cockney History and Culture.

Tower Hamlets Council Recognises Cockney English as the Vernacular of the East End

In a groundbreaking decision, Tower Hamlets Council has agreed in principle to recognise Cockney English as the vernacular of the East End. Why has it taken so long and what does it mean?

Can the working classes speak?

“There’s a world outside of the manor and I want you to see it

Dizzie Rascal – ‘World Outside’

I can see it [x3]

Can you see it?”

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s 1988 essay, “Can the Subaltern Speak?”, posed a fundamental question about the possibility of the marginalized to be heard. The essay was a significant contribution to the Subaltern Studies Group (SSG) and its lineage can be traced back to historians of the English Working Class, such as Eric Hobsbawm, E.P. Thomson, Rodney Hilton, and Christopher Hill.

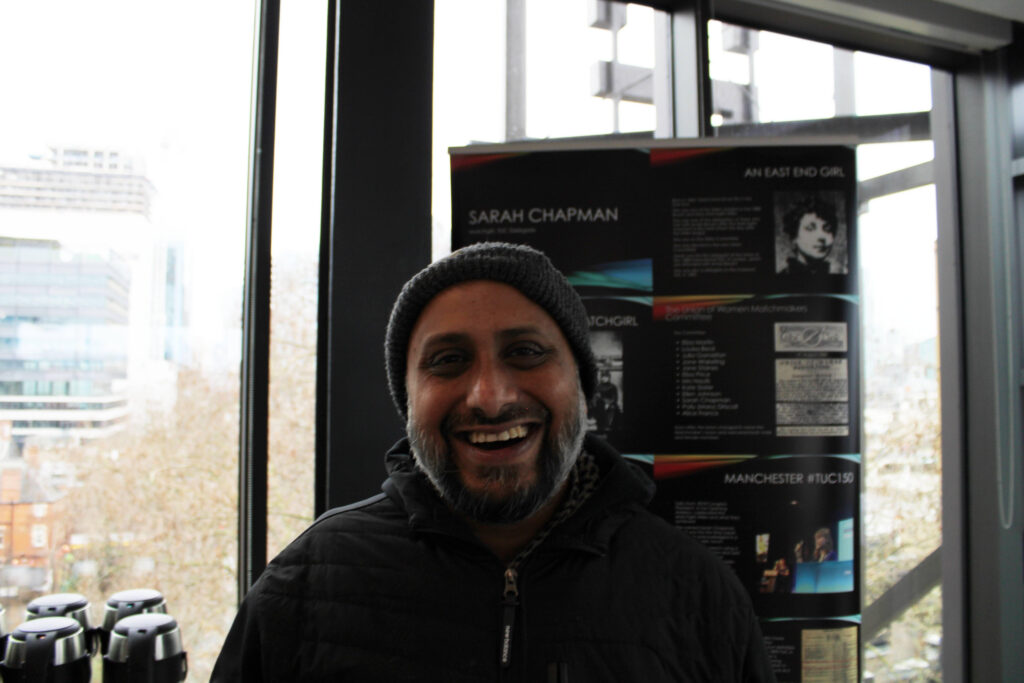

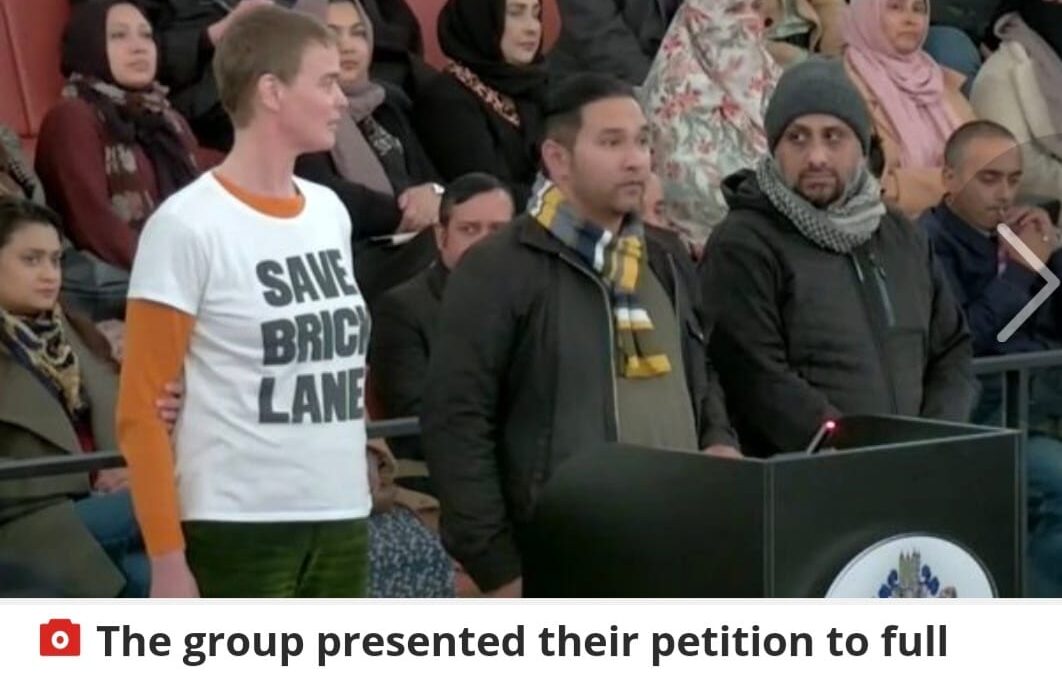

Fast-forward to March 2023, and the Tower Hamlets Council’s recent decisions have brought the debate full circle. On the 1st of March, the Community Language Service was reinstated. Then on the 15th of March in principle recognized Cockney as a Community Language. The council agreeing in principle for provisions of Cockney to be taught and for the promotion of Cockney history and culture.

A decision that has an impact beyond Tower Hamlets. For, since the early 20th century, the Cockney community expanded out from its traditional heartland of inner and East London. For example, pie’n’mash shops, regarded as a staple of Cockney tastes, can now be found as far afield as Bishop’s Stortford in Hertfordshire, Southend in Essex, and Rochester in Kent.

This has led campaigners who brought the petition to recognise that ‘Bow Bells’ is heard through the heart’ where Cockney identity can be marked as an emotional attachment, an affinity with the ‘common Londoner’.

The council’s decisions are part of an ongoing historic struggle in the East End and London in general for the marginalized to be heard and associated movements. As Spivak’s essay suggested, whether the subaltern can speak has been central to the fight for representation and recognition. The council’s recognition of Cockney as a Community Language is a significant step in this ongoing struggle.

So what is this history?

Cockney: A common people’s history of resistance against silencing

“You ain’t gotta gas I’m gas fam” (Don’t gas me)”

Dizzie Rascal – “Don’t Gas Me”

“You ain’t gotta gas I’m gas fam” (Don’t gas me)”

For centuries, the unique dialect of Cockney English has shaped the identity and culture of the working-class community in the East End of London. Its distinct vowel sounds, glottal stops, and rhyming slang have earned it recognition as a dialect in its own right, spoken by generations of Londoners.

The origins of the term “cockney” can be traced back to the Middle Ages, when it was used to describe a small, misshapen egg. Later, the mythical land of Cockaigne became humorously associated with London and by 1600, the term was particularly associated with the Bow Bells area. However, Cockney vernacular and culture have long been resisted by those in power, resulting in creative responses by the Cockney community to their attempted silencing.

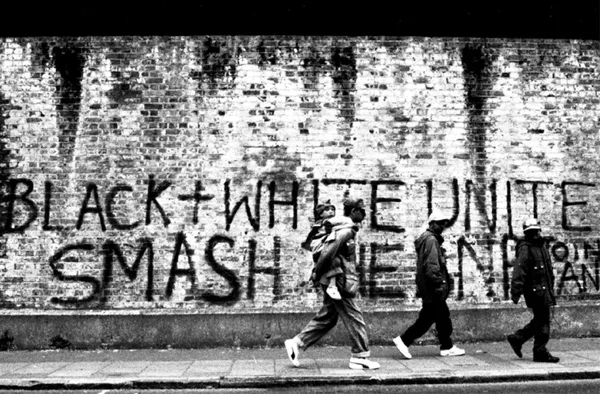

A long-standing feature of London’s cultural fabric, the Cockney dialect and its associated traditions have faced a litany of obstructions at the hands of those in positions of authority. Throughout history, however, Cockneys have displayed a remarkable resilience in the face of these efforts to silence their voices.

One such example occurred when the Fabian Society launched a scathing critique of the work practices at Bryant and May. The company’s management, stung by the criticism, demanded that their employees sign a paper disavowing the allegations made by the Fabians. In a bold act of defiance, the workers refused to comply, resulting in the dismissal of one employee on a spurious pretext. This act of aggression served as the spark for a strike that saw 1,400 women and girls refuse to work by the end of the first day. The strikers, undeterred, marched on the Fabian Society’s offices, forcing the Society’s Annie Bessent to offer her support for their cause. Through this act of collective resistance, the Cockney community demonstrated their tenacity in the face of injustice and their determination to safeguard their voices.

Throughout history, there have been repeated attempts to silence Cockney culture and vernacular, such as the resistance to the Cockney Poets of the 19th century and the criminalisation of Grime and Drill music of the modern East End. These attempts can be seen as an attack on the class background of the authors and their aspirations for the highest level of the art scene.

Cockney culture and vernacular have been dynamic and multicultural, reflecting the migrant history of London and its status as a global city. Loan words have been incorporated with ease, and the vernacular has evolved over time, for example, the phrase ‘shufti with the mufti’. While linguists argue that Multicultural London English (MLE) should not be seen as a competitor to Cockney, but rather an evolving iteration.

In light of the passing of the Equalities Act in 2010, which protects marginalized socio-economic groups, it is perplexing that public bodies continue to ignore Cockney vernacular, culture, and history. The silencing of Cockney identity is an indication of a continuation of the historic prejudice against common Londoners, infantilizing them and expecting them to fulfill their roles of being seen but not heard. It is time to recognize the patchwork quilt of London’s diverse vernaculars and embrace the dynamic and multicultural nature of the city’s identity.

So what is the source of this resistance?

Deconstruction of the hierarchy of public space, institutions, and discourse in London

“I’m G.H.E.T.T.O please don’t act like you don’t know

Dizzie Rascal – “G.H.E.T.T.O.”

I stay called up when I roll,”

Upon conducting a cursory search of the various Cultural Policies introduced by the Mayors of London, it quickly becomes apparent that there is not a single reference to Cockney culture, history, or vernacular. This omission serves as a stark reminder of the longstanding prejudice that continues to be directed towards the common people of London. They are expected to occupy a subservient position, to be seen but not heard, and to remain pigeonholed into mutually exclusive and neat categories of identity. Such a taxonomy, reminiscent of a ‘Human Zoo’, is woefully out of step with the realities of the mixing and evolution of a common London identity and vernacular – what we might term Modern Cockney Culture.

The policing of set roles is a phenomenon that is strictly enforced, as sociologist Erving Goffman astutely observed in his seminal work, ‘The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life’. Whenever common Londoners come together and refuse to conform to their prescribed roles, they are swiftly shut down. This was evident in the debate around Low Traffic Neighbourhoods, and also in the withdrawal of art funding that was meted out to filmmaker Rowdy Sharman.

The historical marginalisation of Cockney culture and vernacular is a cause for concern, particularly when one considers the diversity and richness of the East End’s linguistic heritage. It is imperative that public bodies recognise the importance of supporting and promoting Modern Cockney Culture as a vital component of London’s cultural identity. Failure to do so risks perpetuating the infantilisation of common Londoners and reinforcing the outdated and restrictive stereotypes that have plagued the East End for far too long.

What is the lasting effect of such attitudes?

Would you, Adam and Eve It!: The fantasy vs the reality of modern cockney culture

“You people gonna respect me

Dizzie Rascal – “Respect Me”

Better make you respect me [x4]”

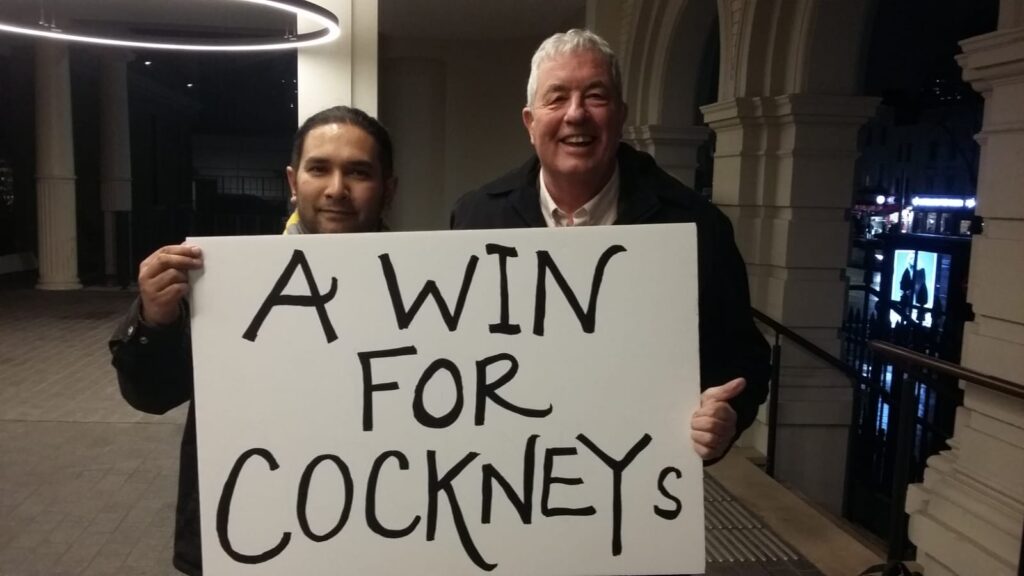

The disconnection from reality in relation to London’s working-class population was brought into sharp relief on the night when the petition was presented. A hostile Labour councillor subjected us to questioning that effectively denied the existence of a common vernacular and culture among ordinary Londoners.

After the presentation of the petition, we repaired to a nearby curry house to celebrate with a hearty meal. Whilst helping myself to a second helping from the sumptuous buffet, I was approached by a group of Bangladeshi diners who identified themselves as Aspire activists, all of whom were first-generation Bangladeshi immigrants. They took the opportunity to express their gratitude for the petition and to emphasise the fact that the Cockney language and culture were an integral part of their community culture. They went on to make a telling political point by stating that, despite my former status as a Labour councillor, they supported the petition because it was of benefit to the community.

The decision by Tower Hamlets Council to recognise Cockney English as the vernacular of the East End represents a momentous occasion that should be applauded by all those who value linguistic diversity and cultural heritage. It acknowledges the pivotal role that language plays in shaping our identities and communities and demonstrates the respect and appreciation that should be accorded to the rich linguistic heritage of the East End.

This example serves to underscore the reality on the ground, where ordinary Londoners have once again come together to create a common vernacular and culture of inclusivity. Against the backdrop of the current political climate, with the political consensus adopting a rhetoric that demonises refugees (whether they are stopped on boats or small boats is immaterial). It is more important than ever for public bodies to promote and sustain the modern Cockney culture and vernacular. As Danny Dyer might say, it’s high time for our politics to embrace a new lingo!

Further Information on the Modern Cockney Festival 2023

Recent Comments