Running battles in the East End between communities, developers and the local authority, what do they have in common? Can the demands articulated by campaigners in regard to the Whitechapel Bell Foundry and Brick Lane be put into a concrete practical program of Community Wealth Building?

In his book ‘Rebel Cities’, David Harvey places the city first and foremost in terms of its position as a generator of capital accumulation instead of, say, the factory. This is justified by an economic argument around the importance of capitalism of land, rent and speculation rather than production. The battle being who has a say over the surplus generated, the forces of capital or the ‘urban proletariat’. Linked to this, is the struggle as to who defines and controls the cultural surplus of a city, its heritage.

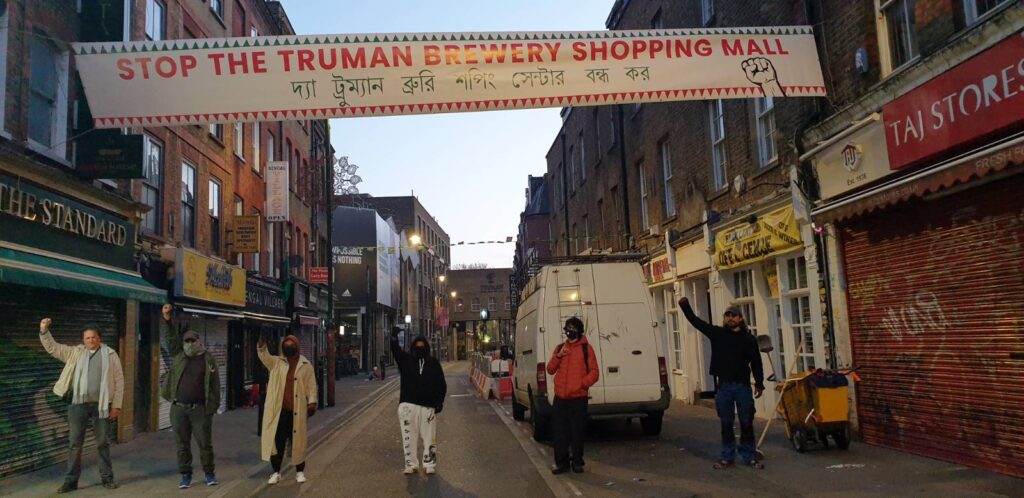

In East London, after a decade of austerity and development policy resulting in social cleansing. Working-class communities have made alliances with the traditional heritage lobby to take on the forces of developers and the unrestrained forces of capital. A physical manifestation is the battle lines being drawn in and around the traditional East End of London, along an invisible line dividing the financial centre of the City of London and traditional working class neighbourhoods. At one end, there is the battle over the Boundary Estate, then a walking distance south is the battle over the historic Truman Brewery. Both are landmarks in the area, signifiers of the struggle of working class communities in the past, fighting for a better future.

The Boundary Estate was the first purpose built social housing estate in England, inspired in design by the philosophy of William Morris. There residents are engaged in a prolong battle with the local authority over its plans to implement a Low Traffic Neighbourhood. The point of contention is the fact that the local authority chose to ignore a traffic management plan drawn up by residents, in favour of the one drawn up by its traffic consultant. At one point, residents stood in front of bulldozers to stop workmen from damaging the fabric of the estate.

Then walking distance to the south, there is the Truman’s Brewery, which in the 70 and 80s was the front line for the local Bangladeshi community in organising to stop the National Front from marching down the now iconic Brick Lane. Today the descendents of those anti-fascist have organised online to generate thousands of letters of objection, preventing the owner, in transforming the site into an extension of the City of London, with no provisions for housing in an area with a chronic housing shortage. Activists and community groups are drawing up their own community plan, with provisions for housing as an alternative to the one proposed by the developer.

Around the corner from Bricklane is the Whitechapel Bell Foundry. Here you have the forces of global capital represented by American developers proposing a boutique hotel, with a sop to kitsch cultural homage to the history of bell making in the area. Aided and abetted by the local council planning authority, whose function it appears is to aid such forces. Opposed by an unlikely alliance of heritage enthusiasts, the local mosque and the local working-class communities. This ‘rebel’ alliance has put together an alternative proposal to keep the site as a working foundry, generating over 25,000 letters in support. The matter has now gone to a planning enquiry with both competing proposals, being argued out in front of the planning inspector. On trial in effect are the two competing visions of the East End, one that serves the interest of Capital and optimal land values versus an East End that serves the working-class communities that live there. Soon the Secretary of State, Robert Jenrick, will publish his adjudication on the matter as to which vision of the East End will triumph in a post-Covid urban London.

In each of the campaigns, there is a collective community effort for the common good. In order to keep the value produced under the control of residents who produced it. What David Harvey calls the ‘right to the city’. A double-pronged political attack, forcing public institutions to supply more in the way of public goods, for public purposes, along with the self-organization of whole populations to use and supplement those goods. The goal is not some theoretical exercise, but actual implementation of policies that have been tried and tested, known as Community Wealth Building.

Community wealth building is a local economic development strategy focused on building collaborative, inclusive, sustainable, and democratically controlled local economies. We have community wealth cities in the United States such as Richmond, Boston and Cleveland. In New York, there is the Bedford-Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation is often considered the first community development corporation, founded in 1967 with encouragement from Robert Kennedy. Since its establishment in 1967, it has helped attract more than $500 million in investment, placed over 20,000 youth and adults in jobs, and helped construct or renovate 2,200 units of housing. In the United Kingdom, we have the ‘Preston Model’, brought over to here by Matthew Brown the current leader of Preston Council.

One of the policy tools deployed in Community Wealth Building is that of the Community Land Trust (CLT). CLTs are non-profit, community-based organizations designed to ensure community stewardship of land. An alternative, inclusive model of land ownership and capital, that can de used to protect cultural and human capital in traditional working class communities.

The above battles in the East End are set in a backdrop of a divided capital along the lines of wealth with ever-growing inequalities. A growing gap and struggles, not just witnessed here in London but in global cities throughout the world, from Bombay to Barcelona. Problems of poverty and deprivation, as a local councillor, I deal with on a daily basis via the phone, face to face through my twice-weekly surgery and home visits in the weekend. In those many conversations, a common theme that occurs again and again, lessons from the rich history of the area, act as a reference point in discussing possible solutions. A collective memory, reinforced by physical landmarks, of resilience, action and hope and not just one of grinding poverty. Muhammad Yunus, the founder of the Grameen Bank in Bangladesh, defined poverty, as a mental state of hopelessness. For my working-class residents’ history is not some academic exercise, but a source of inspiration and hope. A ‘People’s History’ that brings in its wake, localised conflicts about whose collective memory, whose aesthetics and whose benefits are to be prioritised.

Reflecting and looking back, five years ago, I helped launched a political education program, the People’s PPE. The first event a People’s History of Politics was held in the East London Mosque, across the road from the Whitechapel Bell Foundry. The event was headlined by the Guardian journalist Owen Jones, the then Politics editor of the Daily Mail, Peter Oborne, with historian and local resident Dr Layli Uddin. Five years on, together with the local community, we are now involved in the struggle to defend that history in a post-Covid-19 world.

#RightToTheCity #ForTheMantNotTheFew

Recent Comments