Once upon a time in Covid Times during #Lockdown…

Lockdown and isolation, like a lot of men, have forced me to grow my hair and beard long. It was kind of novelty and amusement pursuing the caveman look, going back to nature. The comments at work were mixed. From the regular shouty comment from my manager, “Oi, get a hair cut!” to “Is everything OK at home?” Then as the hair and beard grew the comments changed, especially from female co-workers, “Hello!” “You look different”, “Have you got a new girlfriend?” One person stopped in the middle of the office, looked at me, outstretched her arm, pointing at me and announced “Puru…, you are with it”, and then walked off. Leaving me and others to ponder as to what she actually meant.

One early evening, running into the local corner shop without my customary hat, the shopkeeper said, “Are you into baul music (Bengali folk music)? You remind me of Tagore”. As I walked home, I realised that the shopkeeper shed more light than a shadow in a moment of light-hearted humour. He identified the mighty tradition of Bengali radicalism and placed my face within it.

Bengal Radicalism and its many streams of consciousness

Modern-day Bangladesh is a country made up of the delta created by the two mighty rivers of the Indian subcontinent, the Ganges and the Brahmaputra. Just like these mighty rivers and their tributaries leave a rich alluvial soil to make it fertile agricultural land, so the many cultural streams that flow within make Bangladesh and the wider Bengal the intellectually rich multicultural heartland of South Asia.

Modernity and global capitalism came to Bengal in 1757 at the barrel of a musket, with the corporate sponsorship of the East India Company. At the same time capital was organising Labour in Britain to be the grist to the mill of industrialisation, it was organising labour in Bengal through a process of deindustrialisation, similar to Ireland, to be a cash crop producer to fund the Industrialisation.

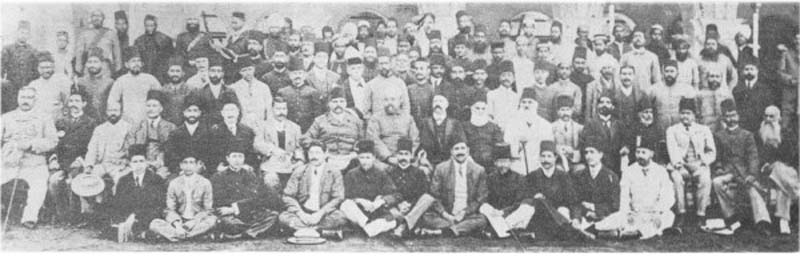

On the ground, it meant huge disruption and disenfranchisement, leading to famine in the 1770s, Warren Hastings report confirmed a third of the population was killed. The Impact of which is still seen today, with the high incidences of diabetes due to the genetic adaptation of going through constant famines. But with this assault on the population came resistance, armed, intellectual and political. Like the rivers that feed into Bangladesh, many intellectual streams have fed into this hotbed of Bengali intellectual radicalism, resulting amongst other things the formation of the independence movement, Congress in Calcutta and the Muslim League in Dhaka.

Rabindranath Tagore, The ‘Grand Babu’ of the Bengal Renaissance

The Ganges starts at the foothills of the Himalayas in Kashmir, winds it way through the north Indian plain and deposits its self into the Bay of Bengal. On the eastern edge of the Ganges Delta is the Hooghly River, where the twin cities of Calcutta and Howrah are situated. It is in the city of Calcutta, that Rabindranath Tagore was born, the epicentre of the Bengal Renaissance.

The Bengal Renaissance was the outburst of Bengali literature, following the 1857 armed uprising against the rule of the East India Company. With intellectuals from both religious communities of Bengal. Hindu writers such as Ram Mohan Roy (before 1857) and Iswar Chandra Vidyasagar as well as Muslim writers such as Syed Amir Ali, Mosharraf Hussain and the ‘rebel poet’ Kazi Nazrul Islam.

Tagore and his family were at the centre of the Renaissance. Tagore although an anti-imperialist was not an ardent nationalist, he was a cosmopolitan. He does not indulge in mirrored reactions; that is to denigrate the Western culture in return for their denigration of the non-Western. In contrast, Tagore attempts to draw an overarching bridge between the East and the West. He engages in an attempt to find harmony and unity in its true essence, a call to be one with “the infinite”, world civilisation. We can observe this in his novel The Home and the World. His conception of this world civilisation is located in the interactions between colonial and postcolonial, East and West, tradition and modernity. A cosmopolitan, fluid and dynamic relationship. His artistic contribution was recognised globally, when he received the Nobel Prize for literature in 1913.

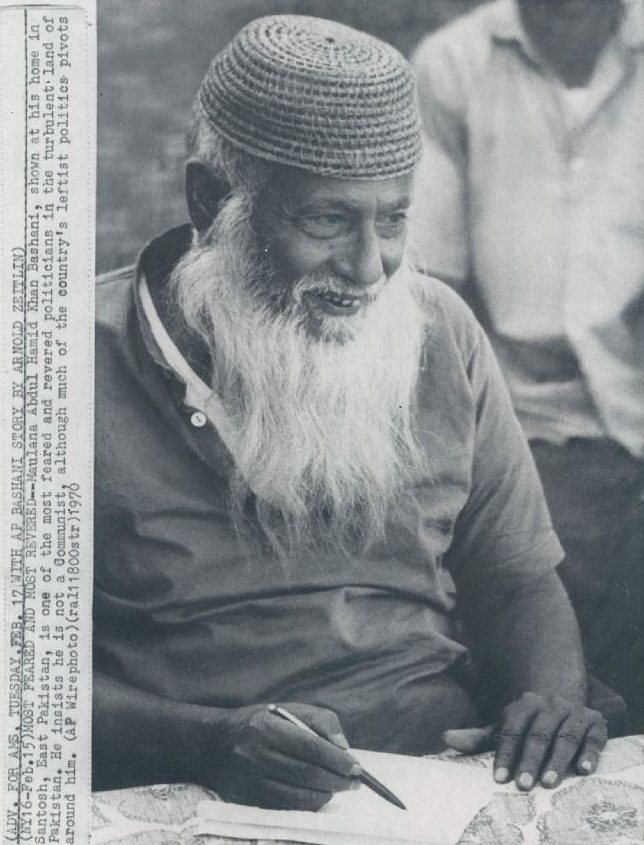

Moulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani: The Red ‘Mao-lana’

Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani is the other pillar of Bengali radicalism. A grassroots organiser, he mixed the Sufi religious tradition with Marxism, to formulate a Liberation theology. Born on the banks of the mighty Brahmaputra river, in now modern-day Assam. His life followed the course of the river, which starts in the glaciers of Tibet and winds itself through the Himalayas eventually joining up with the Ganges in Bangladesh, being buried in Tangail near a tributary of the Brahmaputra.

Bhashani was sufi, and self-avowed Maoist, founder of the Awami League and a seminal figure in the Bangladesh Independence movement. Bhashani’s story begins at an encounter with a Sufi from Baghdad. Guided by the mystic, he enrols at the anti-imperialist seminary of Deoband. After completing his study at the hands of the 1857 resistance fighter and theologian Mahmudul Hassan, he returns to Assam to take up a teaching position. There he saw first hand the exploitation of Muslim tenant farmers faced from the xenophobic Line System.

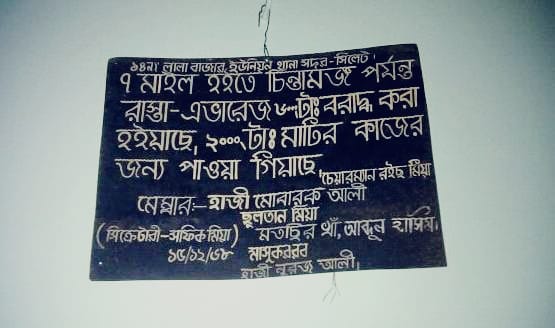

This spurred the Moulana on his long political journey to emancipate his people; to economic liberation from the feudal system, to political liberation from the British Raj in 1947, political freedoms from the Sandhurst educated Rawalpindi generals of United Pakistan, and hunger from the ravages of the 1974 Bangladesh famine. Spanning three nationhoods, his last great public act was against India’s hydro hegemonic erection, The Long March of the Farakka Dam in 1976, which is arguably the last time a Bangladeshi politician was taken seriously in the Indian Parliament, the Lok Sabha.

Bangladesh and the making of a multi-racial Working Class in the East End

“The working class did not rise like the sun at an appointed time. It was present at its own making.” – E.P. Thompson ‘The Making of the English Working Class’

“There is not a thought that is being thought in the West or the East that is not active in some Indian mind” – E.P Thompson

The radical historical roots of Bangladesh have had an impact on working-class politics in the East End. Tower Hamlets has one of the oldest continuous and largest Bangladeshi communities in Western Europe. Bengalis have been coming to the East End of London for nearly 400 years, starting with the commercial activities of the East India Company. The oldest literary record is that of the Bengali Muslim I’tisam-ud-Din, who arrived in Britain in 1766 and published his experience in 1785 as Shigurf Namah i Vilayat (“The Wonders of Europe”). However, by the mid-1970s and with increased racialised restrictions on Commonwealth migration, these migrant workers had begun to bring their families over, worried that they might be permanently separated if they did not act.

Building on the collective memory of the rich political tradition of civil disobedience in Bengal and Bangladesh, the Bangladeshi diaspora in the East End have had countless radical engagements and political mobilisations. From collectively standing up against institutional racism in the Brick Lane strikes against the police, to protesting against illegal deportations of Afia Begum, this spirit and tradition lives on.

Recently, researcher Shabana Begum has chronicled the actions of the Bangladeshi community in the East End who formed the Bengali Housing Action Group (BHAG) 45 years ago. She is currently working together with local Bengali film maker Fahim Alam in a new upcoming documentary on this topic. Their work looks at hundreds of Bengali families confronting an institutionally racist housing system and the ferocious rise of National Front violence, organised into a formal squatters organisation and began to challenge the local Tower Hamlets council and the GLC, for fairer housing options for the community. This tradition still goes on today with groups like Nijjor Manush rallying the youth to save the iconic Brick Lane from destruction by developers.

Man in the Mirror: Bangladesh and me

My connection with the radical political traditions of Bengal begins with my year-long interaction with my uncle in Bangladesh, during an extended family holiday. My uncle started his political career as a student leader, taking part in the 1968 strike to bring down the US backed, World Bank-funded military dictatorship of General Ayyub Khan. He then proceeded to be a Maoist guerilla fighter in the 1971 War of Independence, then after independence got involved in local municipal politics as a local district Mayor or as known in Bangladesh, the Chairman of the Union. Both of us being the inheritor of the political tradition bestowed to us by my great-grandfather, a successful 19th-century tenant farmers leader.

There was always tension between my uncle and me, whenever we spoke, conversations were always short and succinct. We both shared a common enemy, the forces of capital, but disagreed over the methods to tackle it. He was a practical man, a proponent of historical materialism, he saw my Sufism suspiciously as a manifestation, I think of 1960s hippie idealism. As an octogenarian, he recently ran for election and lost. He can now be found in quiet retirement, at the local market, reading his broadsheet newspapers and settling the occasional local disputes. The last I heard from him, he just survived another political assassination attempt, recovering from a minor wound. An occupational hazard of doing politics in today’s Bangladesh. Or in his words a casualty in a struggle against the forces of capital.

Here in Tower Hamlets, as a Labour Councillor, I am observing the ravages of rising inequalities at the hand of the unfetterd power of capital. A working-class community under attack through the twin forces of gentrification and social cleansing. The radical tradition of Bengal and Bangladesh adds to the existing rich tradition of resistance in the East End. A source of strength for all in the face of insurmountable odds. For there is no beginning, there is no end, the struggle is permanent.

“I’m starting with the man in the mirror

I’m asking him to change his ways

And no message could have been any clearer

If you want to make the world a better place

Take a look at yourself, and then make a change”

– Michael Jackson ‘Man in the Mirror’

Really informative article on many fronts. Most of all my ignorance of recent Bengali history. Tagore though was taught, well some of his poetry, in my east end white school in the 60’s.

My father, the late Indian poet and novelist Tarapada Ray, studied under Moulana Bhasani for two years before he left Tangail in 1951 .

to start college in India. As a small child I myself met Maulana Bhasani and visited his home just north of Tangail. My father told many funny stories about Moulana Bhasani , including his sensitivity about his old age. He was never offended. Bhasani was very fond of my father. I would love to restore his seminary in Tangail.

Dr. Ray I am from Bangladesh, very much interested to listen from you concerning Bhasani. Would you please provide me your e-mail or whats app/ imo/ viber no through which i can connect you.

Here is my email add. mnmillatmafi@gmail.com