A non-theological reflection on the movement to establish a local lunar visibility calendar in the UK, and its place in history and the future in a post-Gaza world.

A Spring Evening at Wanstead Flats: Searching for the New Crescent Moon

On Sunday, 30th March, while my neighbours in Tower Hamlets celebrated Eid, I set out for Wanstead Flats in search of the new crescent moon. The event was organised by the New Crescent Society, founded by my friend Imad Ahmed, who researches lunar visibility calendars at the University of Cambridge. The society’s goal is to establish a UK-wide local lunar visibility calendar.

Muslims follow both solar and lunar calendars—the solar for daily prayers and the lunar for religious festivals. A practice also present in Christianity such as determining Easter, and the Jewish traditions. This year was different, as I decided to be a participant in the debate the Muslim community has this time of the year.

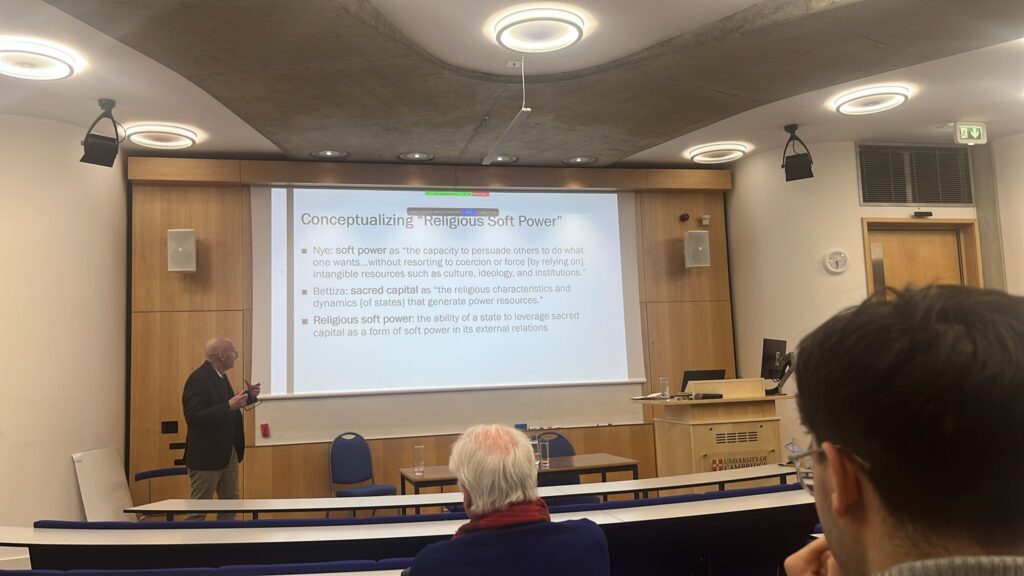

For years, I observed the so-called ‘moon wars’ from the sidelines—the annual debate in the Muslim community in the UK, over when Ramadan should begin and end. In the UK, some follow Saudi Arabia’s moon sighting (mainly in London and the South), while others rely on local sightings (mostly in the North). This division persists, reinforced by Saudi soft power, which uses petrodollars to fund individuals and institutions, aiming to impose a unified calendar under its control—bypassing a millennium of traditional practice.

Western governments, including our own, have largely ignored this Saudi state influence and interference, sometimes even facilitating it. For example, recent declassified US National Archives documents reveal that during the Cold War, the CIA officers in Saudi Arabia wrote literature for Muslims, published and distributed by the Saudi Government to counter socialist influence in the Muslim world and ferment sectarian divisions for geostrategic interests.

This year, I followed a UK-based lunar visibility calendar, beginning my fast a day later than my extended family and neighbours. Out of politeness, I kept it to myself, making this Ramadan a more solitary experience. As it ended, I joined Imad at Wanstead Flats to sight the crescent moon and celebrate Eid. Expecting a small gathering, I was surprised to find over 300 people—families sharing food, prayers, and an open-air celebration.

The BBC World Service was there, recording the event. Their journalist was struck not only by the turnout but also by the festive spirit—proof that Muslims could agree to disagree and celebrate on different days in harmony.

Yet, this is nothing new in the Muslim world, or what some academics call the Islamicate.

The Islamicate: A Culture of Ambiguity, Resistance, and the Ongoing Struggle for Agency

The historian Marshall Hodgson introduced the term “Islamicate” to create an inclusive framework to analyse this history of contributions and interactions in Muslim societies. This framework encompasses not only Muslim actors but also non-Muslims who contributed to the broader civilisation. Therefore acknowledging that the development of what is termed ‘Muslim civilisation’ was shaped by individuals of various faiths.

Examples from Al-Kindi’s contributions to science, to the rich cultural influences of Hindus, as outlined by Richard Eaton in India in the Persianate Age, it is evident that intellectual and artistic advancements were not the exclusive domain of Muslims. And vice versa, Muslim influence on other civilisations, as exemplified by the theological works of the Andalusian Jewish theologian, Maimonides, or the Hindu Bhakti movement in Mughal India.

A recurring theme in this history of the Islamicate is the concept of a ‘culture of ambiguity,’ a term introduced by Thomas Bauer. A zone of ambiguity incorporating agency and autonomy, created by the semantic field of applying the agreed core tenets of the Muslim faith. He challenges the perception of Islam as inherently dogmatic, advocating for a revival of its historical openness.

In A Culture of Ambiguity: An Alternative History of Islam, Bauer explores how classical Islamic civilisation embraced complexity, pluralism, and interpretative openness across theology, law, and literature. He argues that precolonial Muslim societies valued intellectual diversity, allowing for a multiplicity of perspectives. However, modernity, shaped by Western epistemology and colonialism, contributed to a decline in this tolerance for ambiguity, fostering rigid and literalist interpretations.

The ‘culture of ambiguity’ is further explored and defended within Muslim societies and communities by Wael Hallaq, a Palestinian academic at Columbia University, in works such as Shariah, Restating Orientalism, and The Impossible State. I had the privilege of spending a weekend with Hallaq, where he summarised his key arguments and invited rigorous debate from the audience, where he advocated a reconstruction of this culture of ambiguity and agency.

This ‘culture of ambiguity’ is evident in discussions surrounding the lunar visibility calendar in medieval Muslim texts. For instance, the theologian Al-Ghazali noted the common practice of different cities within the same political entity observing Ramadan and Eid on separate days based on local lunar visibility. Demonstrating a long history of decentralised agency within the Muslim world, through a local lunar visibility calendar.

This ambiguity and decentralisation have increasingly come under attack during the era of colonialism, with the introduction of calculations and almanacs authorised by colonial administrators and their successor, the post-colonial nation state. This controlling tendency continues, with a push by the Saudi state and its supporters, through a global unified calendar under their control. Reaching a high tide, before the events after the 7th October.

It appears now there has been a pushback both in the United Kingdom and elsewhere, in a post-Gaza world, against such a unified Saudi-led global calendar

Ramadan In a Post-Gaza World

In 2025, the Indian essayist Pankaj Mishra published his latest work, The World After Gaza, in which he defines the era we live in as the Post-Gaza world. Mishra’s book examines the Israel-Palestine conflict through the lens of colonial history, racial power structures, and Western complicity. He argues that the West has upheld a global racial order that enables Israel’s actions and perpetuates Palestinian suffering. Furthermore, he suggests that the Holocaust was an extension of colonial violence and that its memory has been manipulated to justify Israeli policies.

Ramadan in a Post-Gaza world has been as difficult as the last, with images of Palestinians still subjected to continuous violence—violence that international courts have classified as genocide. In addition, this Ramadan, the United States and the United Kingdom have launched a new bombing campaign in Yemen against the Houthis. A response to the Yemeni blockade against Israel, in response to their genocide in Gaza.

These recent air strikes are part of a decade-long bombing campaign, blockade, and famine, facilitated by the US and UK, resulting in hundreds of thousands of civilian deaths. This, in turn, is part of a century-long war of sustained violence across the region. The origins of this forever war in the Middle East have been documented by the historian David Fromkin in his seminal work, A Peace to End All Peace.

Waged by our government and its US ally to ensure the continued flow of oil at the right price, with the profits directed to Western banks and military-industrial interests. The existence and continuation of this policy were recently acknowledged by the former Chief of Staff to the US Secretary of State, now anti-war advocate, Colonel Lawrence Wilkinson.

However it seems this forever war might be in its final stages, with the rise of a multi-polar world.

A Multipolar Moon for a Multipolar World: An Axis of Resistance

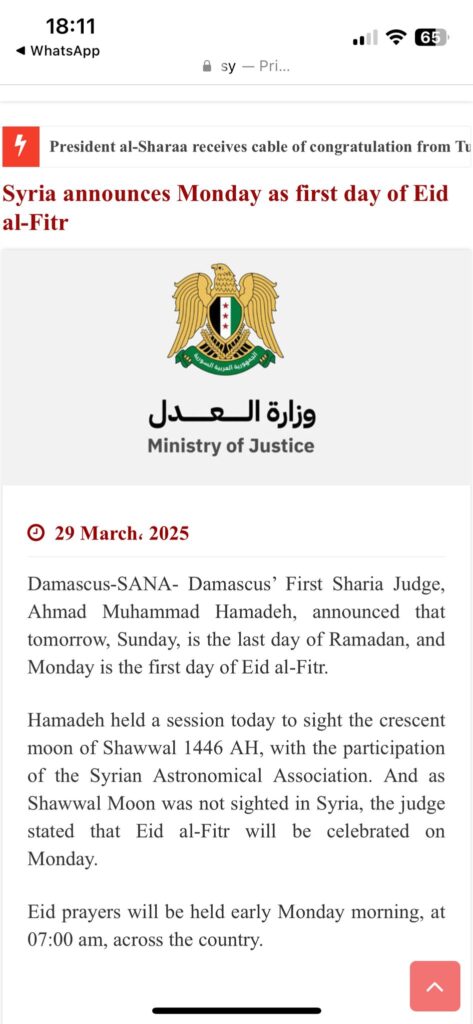

Just as many British Muslims have been asserting their agency by following a local lunar visibility calendar. This sentiment was echoed by three Arab governments bordering Israel, Jordan, Syria and Egypt. Possibly under pressure from their populations, they diverged from Saudi policy and chose to follow local lunar visibility calendars, celebrating Eid a day later. This decision, perhaps, reflects the growing anger towards the Saudi government by local populations for its complicity in aiding Israel in Yemen, and Palestine through the land bridge to circumvent the Red Sea blockade.

As I broke my fast on Wanstead Flats that day, I could not help but reflect that perhaps this movement for a local UK lunar visibility calendar is part of a wider movement to resist empire and its willing executioners. Part of a wider axis of resistance and solidarity, transcending sectarian divisions, ethnicities, nationalities, and faiths.

In one part of the axis, there are daily acts of resistance and agency against occupation displayed by the people of South Lebanon, Southern Syria, and Palestine. They continue to endure the violence imposed by our government and its allies, in defiance of their Western-backed governments.

On the other side of this axis in the so-called democratic West, there are the many Jewish activists arrested and prosecuted for protesting against the genocide in Palestine. Meanwhile, in not so democratic Saudi Arabia, there have also been moments of defiance, with soldiers refusing to fight as well as Saudi pilots have refused to bomb Yemen, forcing the government to hire mercenary pilots instead.

The decision to follow a local UK lunar visibility calendar is not an isolated act but should be seen as part of a long Islamicate tradition of ambiguity, agency, and resistance. In a Post-Gaza world, through this conscious act of asserting agency on Wanstead Flats, we unconsciously participated in a universal tradition—captured in the English language by Henry David Thoreau’s On Civil Disobedience—a small but meaningful act of defiance against power and a commitment to truth.

Following the Prophetic injunction of speaking truth to power. As the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) said, “The highest form of spiritual struggle is to speak the truth in the face of an unjust tyrant.” #Mujahada

Gulzar sahab is Sikh!

Thanks, corrected.