A guided tour to Uzbekistan with Sacred Tours was more than just a holiday; it was a profound journey of rediscovery. As a British Bangladeshi from Sylhet with a Muslim heritage, how this experience was significant to me. On a guided tour with the Cordoba Academy.

Retracing Footsteps Into History

The Indian Independence leader and first Prime Minister of India (1947-1964) wrote his seminal work, ‘The Discovery of India,’ during a pivotal moment in his life. Specifically, he penned it while imprisoned by the British Raj at Ahmednagar Fort in 1944. Similarly, facing a turning point in my life, in a self-imposed exile from the ruthless world of East End politics. I accepted an offer from Sacred Tours, by the Cordoba Academy, to visit Uzbekistan, historically known as Transoxiana, Turkestan, and Mahr Wal Nahr. For me, a journey of rediscovery of what it means to be a British of Bangladeshi origin, from Sylhet in 21st-century Britain.

My interest in Uzbekistan began during my time at SOAS, inspired by the historian Marshall Hodgson’s three-volume seminal work on Islamic history, “The Venture of Islam: Conscience and History in a World Civilization.” Hodgson’s work explores how Muslims from diverse regions such as the Balkans in Eastern Europe and Bengal share a common cultural and religious vocabulary, using terms like namaz, roza, khuda, and mussalman. Additionally, they follow similar religious practices, particularly the Hanafi rites.

To explain this phenomenon, Hodgson coined the term “Persianate,” which he positioned as a crucial component of the broader “Islamicate” culture. This Persianate cultural belt stretches along the old spice and silk roads from Bengal and China in the East, through Northern India and Central Asia, and reaches its western boundaries along the Volga River in Russia, the Anatolian coast, and the valleys of Eastern Europe.

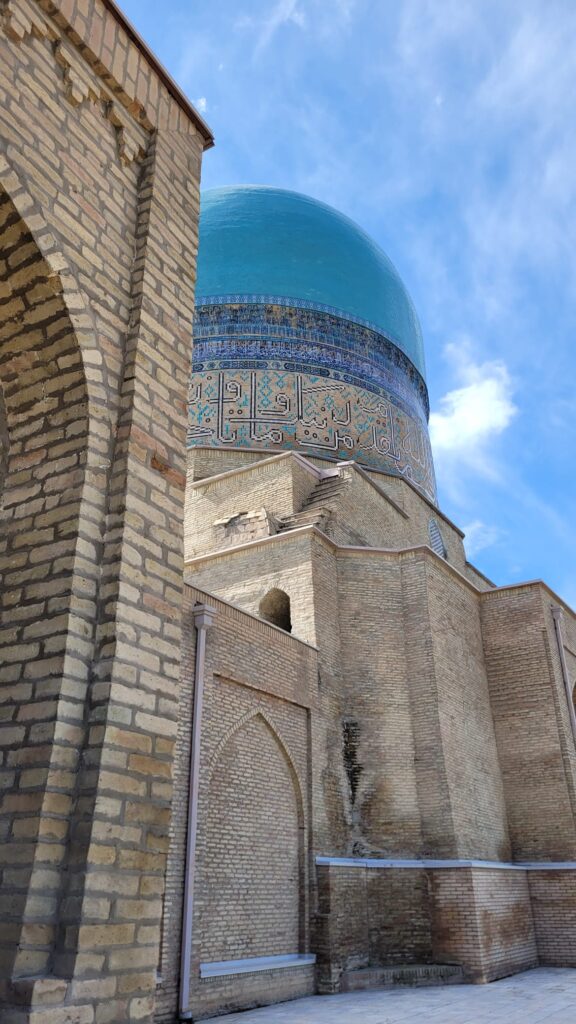

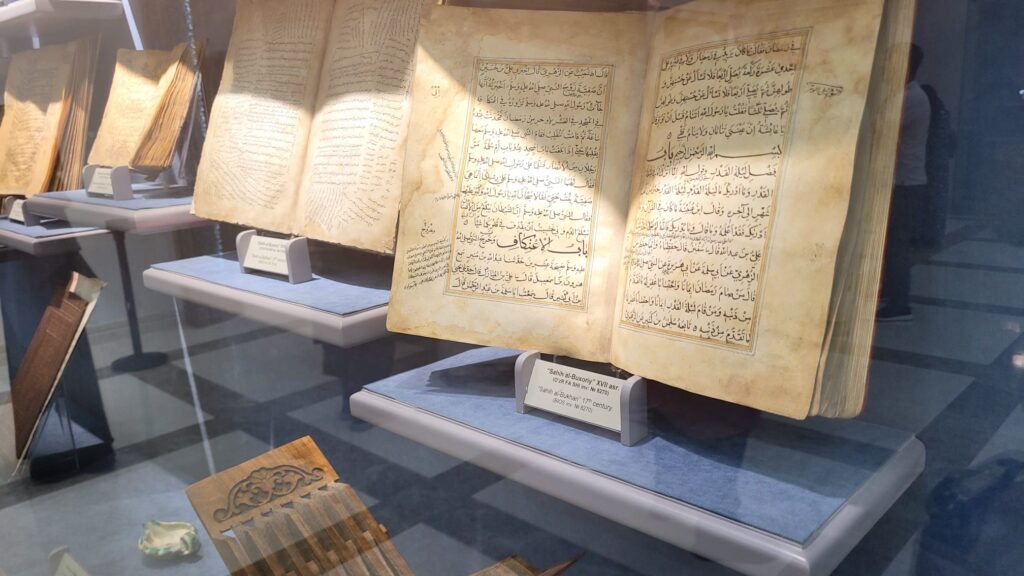

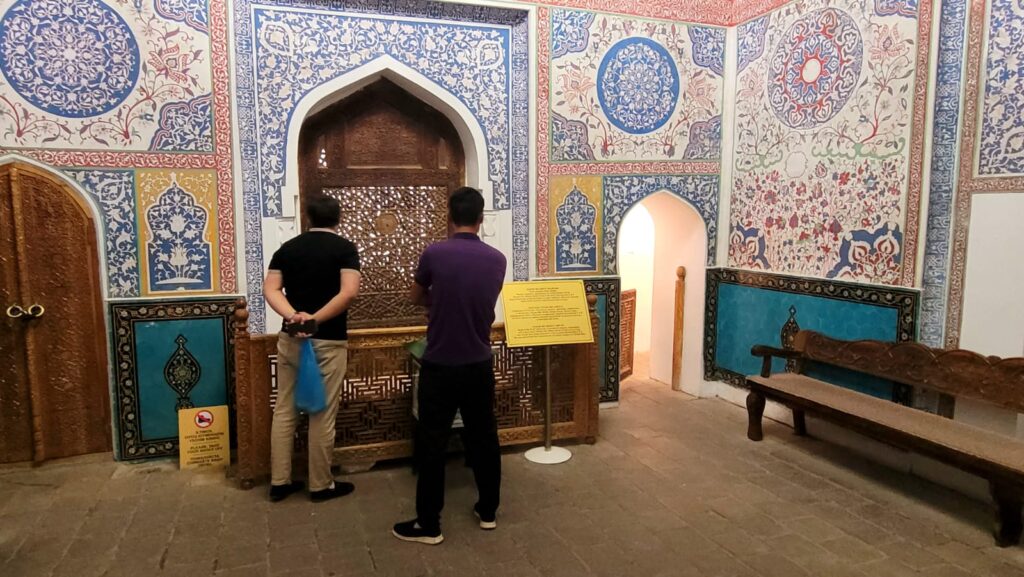

The origins of Persianate culture are not in Iran but in Transoxiana, which is modern-day Uzbekistan and parts of Afghanistan. It was here that Ferdowsi composed his epic of Persian history and language, the Shahnameh. The Hanafi school was established by various scholars, including Burhanuddin Al-Marghinani, the Maturidi school of theology was founded in Samarkand by Abu Mansur al-Maturidi, and the Naqshbandi school of mysticism by Bahauddin Naqshband in Bukhara. These texts and practices are read and taught from rural Bangladesh to villages in the Balkans, and even here in East London, where texts like the Hidayah, the Aqaid al-Nasafi, and translations and adaptations of Jami’s ‘Yusuf and Zulaikha’ are studied.

Therefore, when Sacred Tours advertised their trip to Uzbekistan, I decided to join a group from East London and visit the fountainhead of the culture I was so familiar with.

Springboard of the Axial Age

The term ‘Axial Age,’ coined by German philosopher Karl Jaspers, refers to significant transformations in religious and philosophical thought that occurred across various regions from approximately the 8th to the 3rd century BCE.

“Confucius and Lao-Tse were living in China, all the schools of Chinese philosophy came into being, including those of Mo Ti, Chuang Tse, Lieh Tzu and a host of others; India produced the Upanishads and Buddha and, like China, ran the whole gamut of philosophical possibilities down to materialism, scepticism and nihilism; in Iran, Zarathustra taught a challenging view of the world as a struggle between good and evil; in Ancient israel the prophets made their appearance from Elijah by way of Isaiah and Jeremiah to Deutero-Isaiah; Greece witnessed the appearance of Homer, of the philosophers—Parmenides, Heraclitus and Plato—of the tragedians, of Thucydides and Archimedes. Everything implied by these names developed during these few centuries almost simultaneously in China, India and the West.”

Vom Ursprung und Ziel der Geschichte (The Origin and Goal of History) by Karl Jasper

Uzbekistan was pivotal not only to a large portion of the modern Muslim world but to civilization as a whole. In its western deserts, horses were first domesticated, giving rise to the horse riders, the Aryans/Scythians of history. These horse riders were known in ancient Akkadian as the Umman Manda. The Assyrian king Sargon the Great famously led an expedition against them, resulting in the destruction of his army and the loss of his body. Similarly, the Persian Emperor Cyrus the Great met a grim fate against the horse riders, with his head severed and drowned in a bag of blood by the Scythian Queen. The renowned horses of this region prompted the Han Chinese Emperor, Wu Di, to establish what later became known as the Silk Road, sending out an entire army and setting up garrisons along the route to the Fergana Valley.

Ideas, along with horses and fine silk, travelled the length and breadth of the known world from Uzbekistan. Greeks settled by Alexander the Great in the region converted to Buddhism and spread its teachings into China and beyond. Zoroaster’s teachings were established here before spreading into Persia and India. Additionally, Mani formulated his teachings of Manichaeism in Uzbekistan and spread them along trade routes throughout the Persian and Roman Empires. Even the Christian St. Augustine had disputations with Manichaeans in his native North Africa.

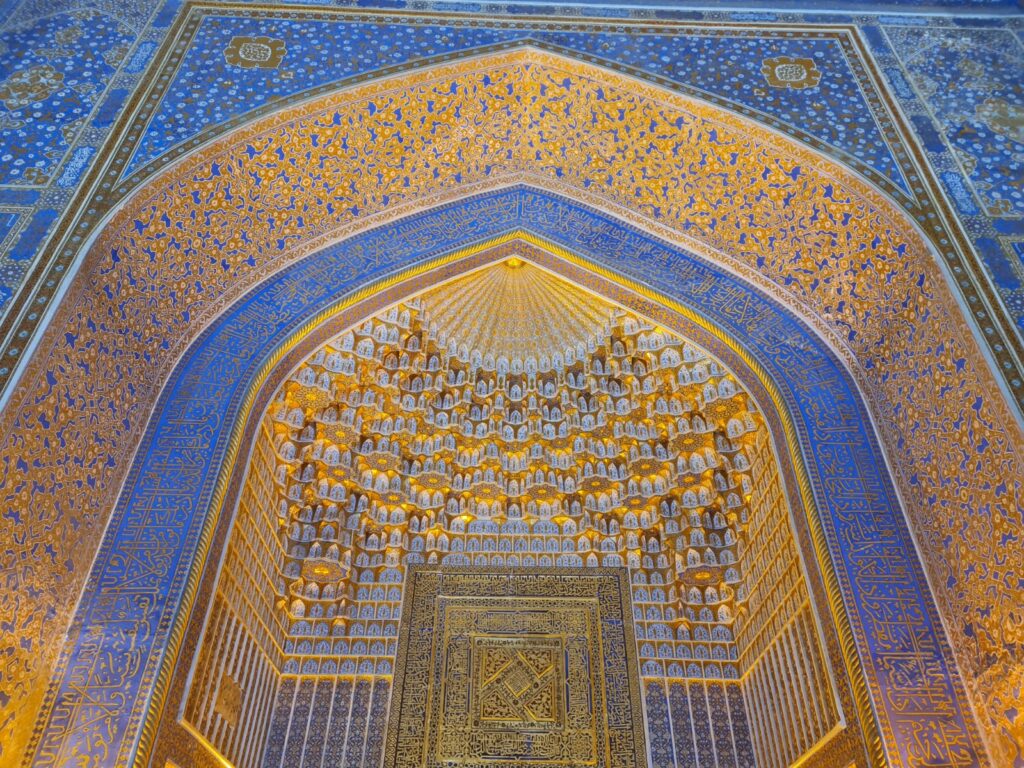

Each religious and philosophical idea, leaves its imprint, eventually resulting in a richly embroidered tapestry of ideas, centred around monotheism, similar to the carpets one finds in the city of Bukhara.

Creolisation and the Islamicate

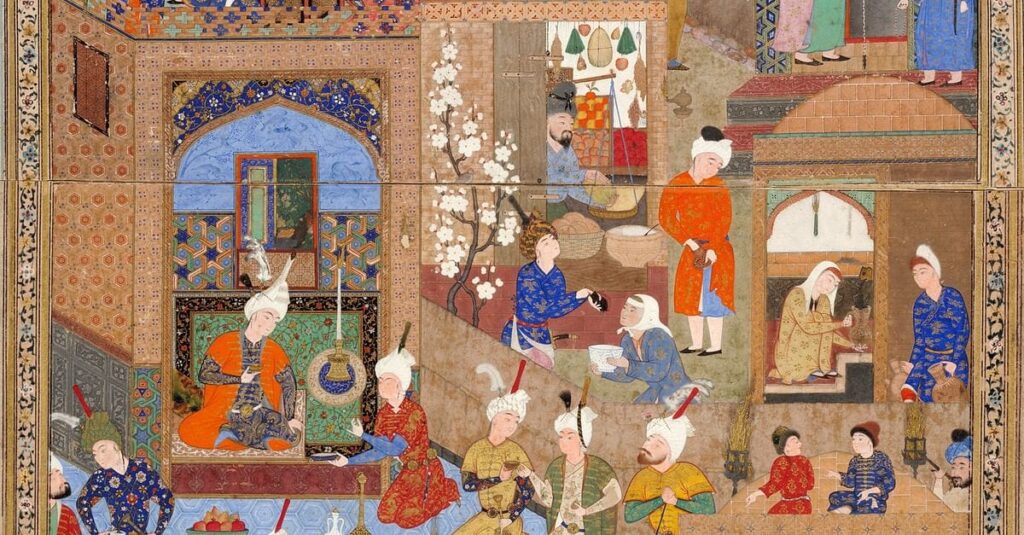

Muslims arrived in modern-day Uzbekistan in the 8th century during the Arab conquest under the Umayyads, entering a diverse cultural landscape. Despite the conquest, the old Persian nobility were allowed to rule. Over time, the local Buddhists and Zoroastrians converted to Islam, though many symbols of these older faiths were preserved and reinterpreted. For instance, the colors and motifs found in the prayer rugs of Bukhara today reflect this cultural synthesis. This blend of influences fostered a rich culture that produced polymaths such as Al-Khwarizmi, Avicenna, Al-Biruni, and Razi, who laid the foundations of modern science, mathematics, and medicine.

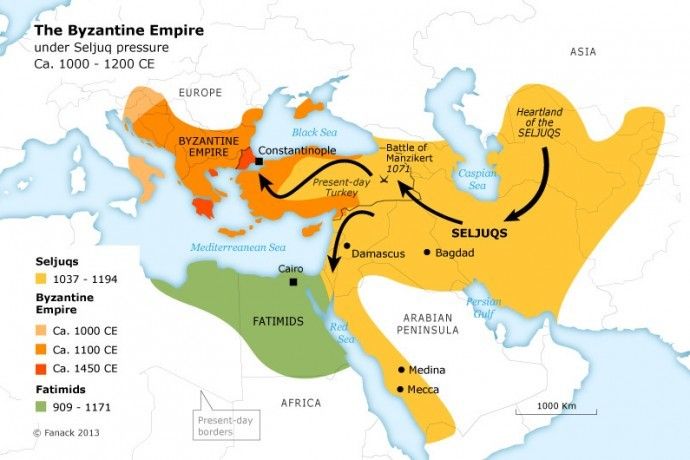

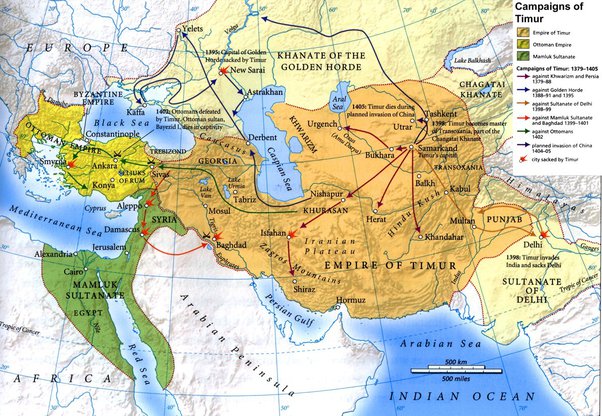

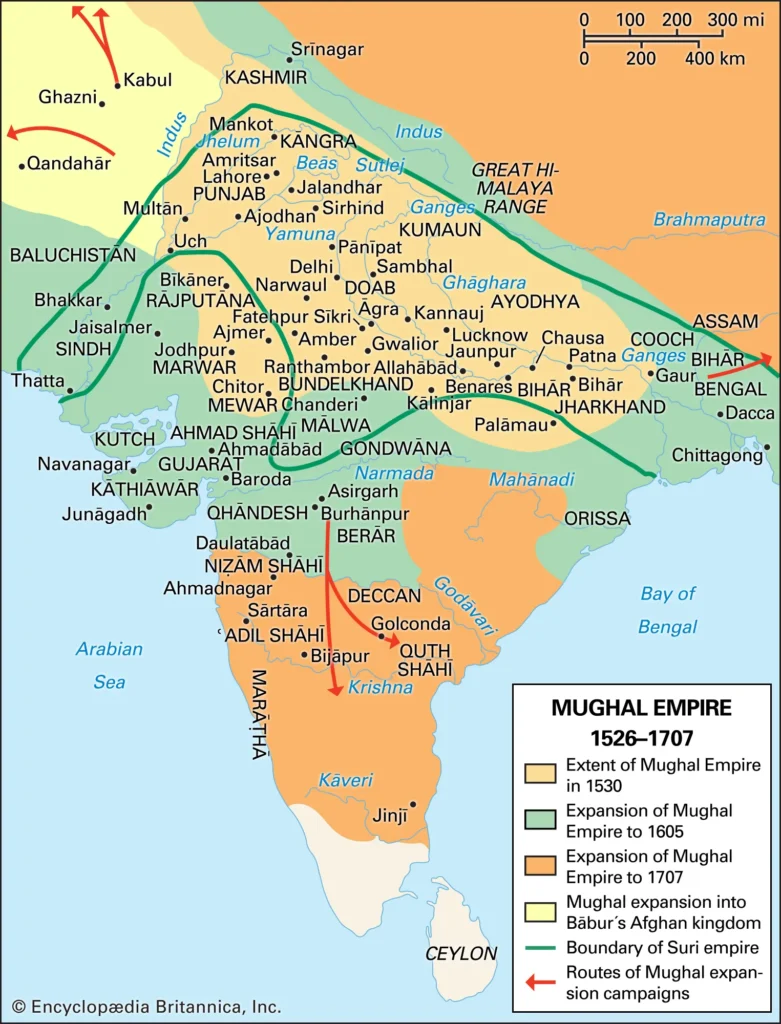

This process of cultural creolisation and Islamicisation extended beyond the fertile valleys into the wild steppes of the horse riders. While previous attempts at conversion by force had failed, Sufis like Ahmed Yasawi succeeded through their gentle words and spiritual approach, winning the hearts of the nomads. This initiated migrations into the Muslim world by Turks and Turkicized Mongols, including the Seljuks in the central Islamic lands, the Ottomans in Eastern Europe and Anatolia, and the Mughals in South Asia.

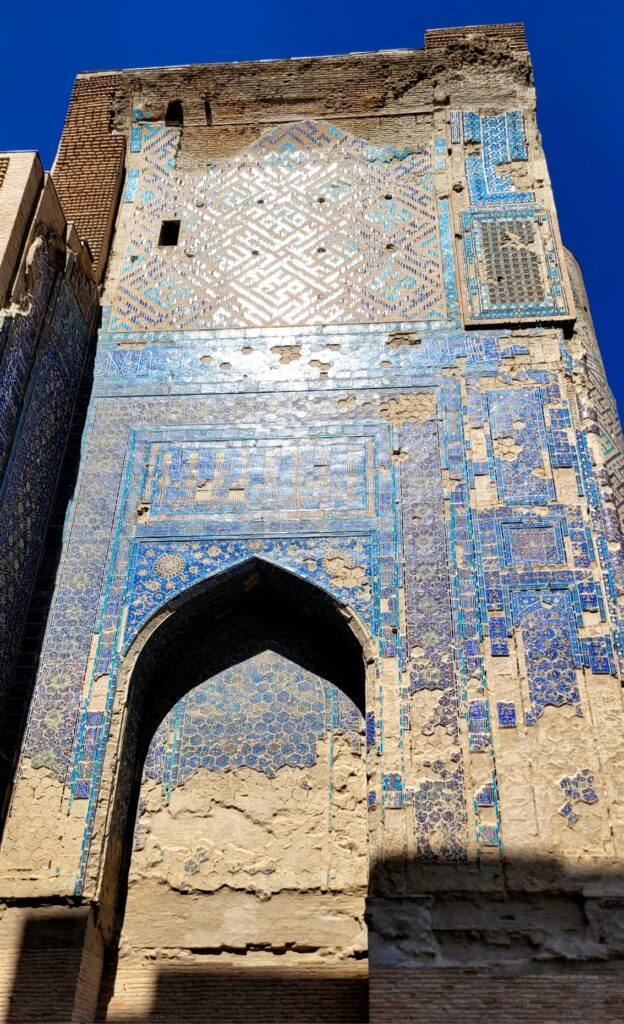

Genocide Then and Genocide Now

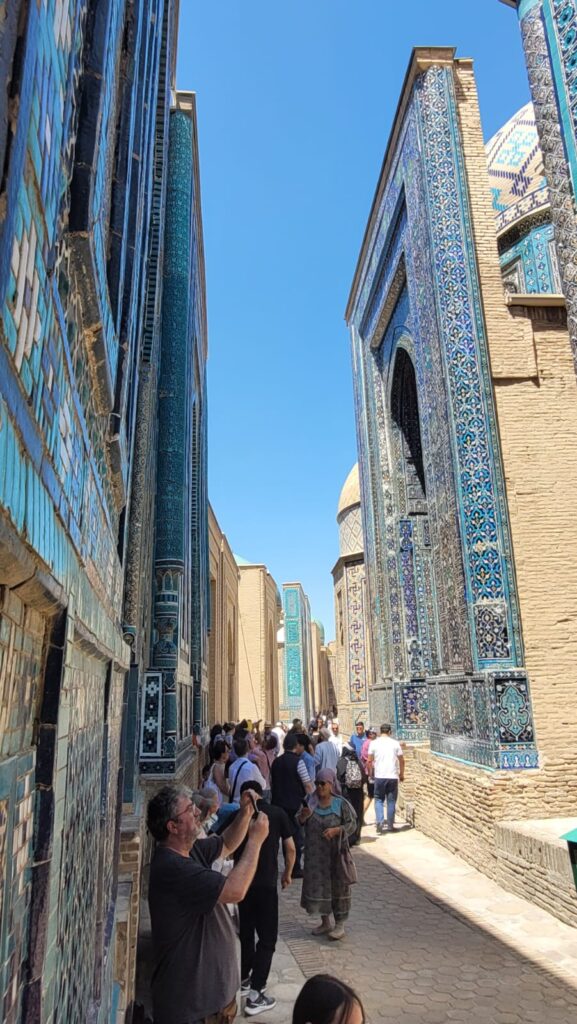

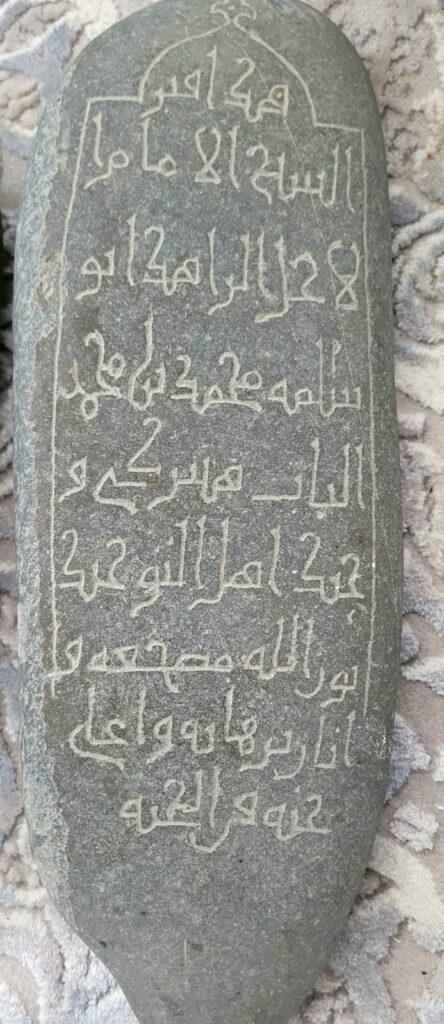

Personally, the most striking feature of the journey was the physical scars left by the Mongol Genocide, which claimed up to 70 million lives. In Uzbekistan, 90% of the population perished. In Tirmiz, only the shrine of Imam Hakim at Tirmidhi remains of the medieval city. Over and over, we found remnants of medieval cities where the only surviving structures were mausoleums, preserved due to the Mongol superstition against desecrating graves.

Many Muslim families fled the Mongol Genocide, settling in Anatolia in the west and South Asia in the east. For instance, the poet and mystic Rumi came to Konya as a refugee. The Ansari family settled in South Asia in various regions: Sindh, Delhi, Lucknow (establishing the famous seminary Farangi Mahal), and Sylhet. In Sylhet, they accompanied Shah Jalal of Konya. Sheikh Shah Farid Al Ansari founded a settlement 7 miles south of Sylhet town, now named Faridpur, renowned for his shrine, mosque, and school, which continue to function 800 years later. Richard M. Eaton details this settlement pattern in his work, “The Rise of Islam on the Bengal Frontier.”

It is no accident that the descendants of the survivors of one genocide, the Mongol Genocide, are at the forefront of protesting against the genocide in Gaza, here in East London. Risking police arrest and detention, for simply protesting against the Genocide of the Palestinians, in the famous Battle of Bethnal Green & Stepney, on the 4th of July 2024.

Everything Returns to Its Origins

Travelling to Uzbekistan felt like visiting Sylhet but without the mosquitoes and humid weather. Our Uzbek hosts were fascinated by the cultural similarities between their region and Sylhet, including honorific titles like ‘bhai’ and ‘apa’. Even the facial features commonly seen in Sylhet were noticeable in Uzbekistan, especially in cities like Samarkand and Bukhara.

One humorous encounter involved my interactions with Uzbek officials. Over two days, they became convinced that I was not a British citizen of Bangladeshi origin but a resident of Bukhara. They insisted, “You no Bengaliski, you Bukhara!” Even as I was leaving, the official shook his head, repeating, “Bukhara, Bukhara.”

Who’s up for going to Uzbekistan next year? Watch this space…

“Return with haste: time passeth swift away;

Christopher Marlowe, Tamburlaine the Great

Our life is frail, and we may die today.”

Details of the Tour – with Highlights – with Sacred Tours of the Cordoba Academy

Sacred Tours plans to organise another trip to Uzbekistan, in September.

Day 1 – Tashkent – Original Uthmani Manuscript of the Quran

Day 2 – Tirmiz – Imam Tirmdhi Shrine and Imam Hakeem Al Tirmidhi Shrine

Day 3 – Sharisabz – Timurid architecture of the city

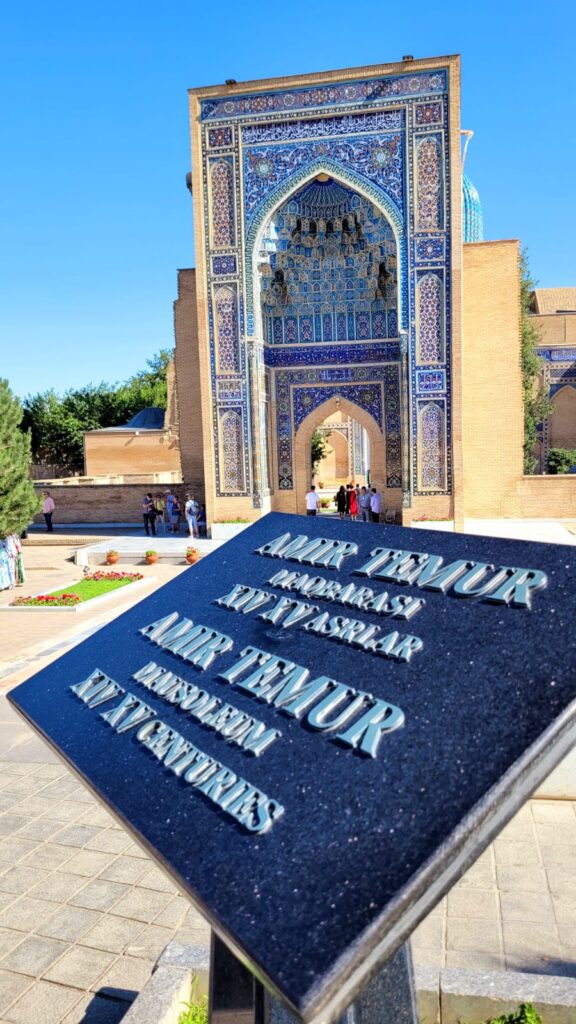

Day 4 – Samarkand – Rejistan Square

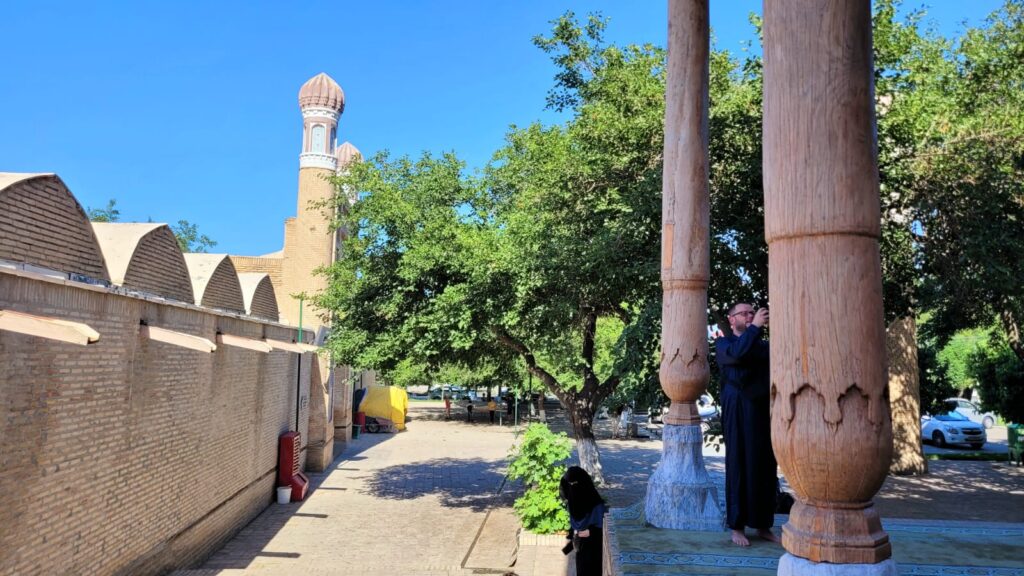

Day 5 – Samarkand – Bibi Khanom, and Khizr Mosque

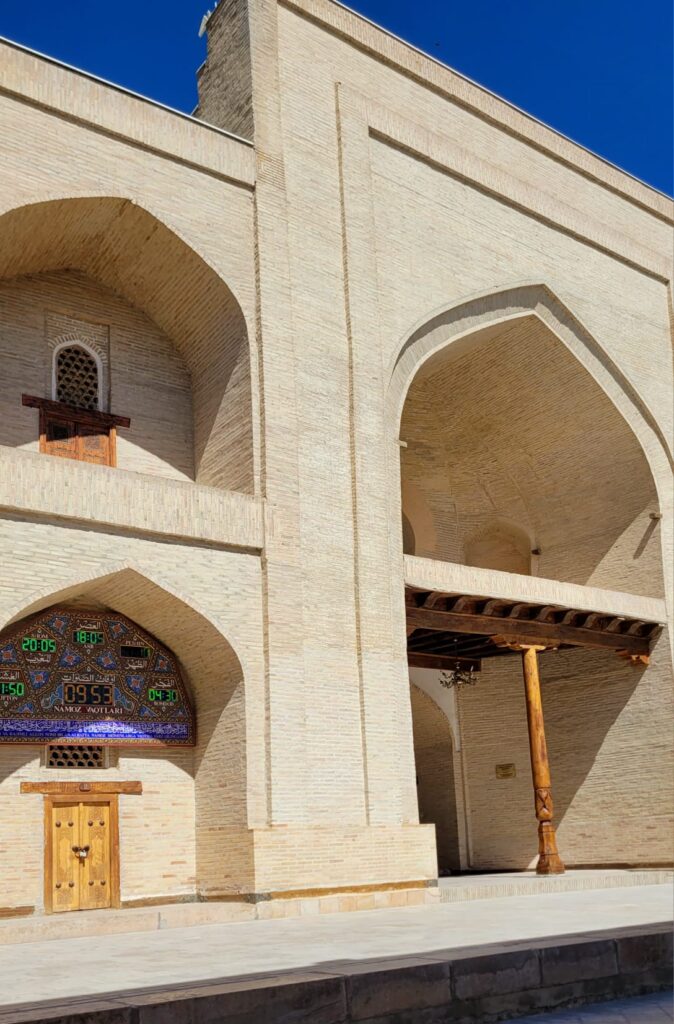

Day 7 – Bukhara – Shrine of Bahauddin Naqshband, Old City

Day 8 – Travel back to Tashkent and home

Link to the Cordoba Academy: https://www.cordobaacademy.com/

Photo Gallery of Trip

Recent Comments