LONG READ: An exploration into the recent 2022 defeat of Labour in Tower Hamlets. In particular, why the party is seen with hostility by first-generation migrants and subsequent generations? Exploring the dynamics of migrant culture in the East End, in particular, the Bangladeshi migrant culture, known in academic literature as ‘Bhadralok’ and the local Labour Party’s ham-fisted effort of interactions with it.

Divided into 9 parts with case studies and references:

- Regime Change: One Year On

- History of Migration in the East End

- Common Misunderstandings: Exclusion of the Migrant Experience from Our Arts

- A case study of the Town Hall

- A case study of the Rich Mix Centre

- Migrants & Modernity: Introducing the Bengal Renaissance & the Bhadralok

- Revisiting Our Assumptions About Modernity

- Home and the World: The Bengal Renaissance

- Introducing the Bhadralok

- ‘Heimat’ – ‘My’ Home and the World: Childhood Experience of Bhadralok Culture in Bangladesh

- The Bhadralok in Britain

- Bhadralok Impact on the East End: Introducing Creolisation as a Framework of Understanding

- Tackling Common Misconceptions: Arguments for Integration & Arguments Against Assimilation

- Assimilation does not work: A Case Study of the Tower Hamlets Labour Party

- So Where are the Bhadralok with Tower Hamlets Labour?

- Tower Hamlets Labour and the Problem of the native misinformant: Political and functional illiteracy

- The Bhadralok Approach to Tower Hamlets Labour

- Breaking Ranks with the Bhadralok?

- FURTHER READING – On Bengali Bhadralok/Bengal Renaissance culture

- Visual Essay on Bengali Bhadralok Culture – Jalsaghar (The Music Room) by Satyajit Ray, 1958

- FURTHER READING – On Creolisation of Migrant Culture in the East End and Contributing to the Richness of the Common London Culture (Modern Cockney)

“আমি ঝন্ঝা, আমি ঘূর্ণি,

আমি পথ-সমূখে যাহা পাই যাই চূর্ণি’।”

“I am the hurricane, I am the cyclone, I destroy all that I found in the path!”

Bidrohi (Rebel) by Kazi Nozrul Islam

Regime Change: One Year On

Following the stunning electoral upset of the Aspire Party of Mayor Lutfur Rahman in Tower Hamlets, Labour suffered a devastating blow that reverberated throughout the political landscape. A reverberation still felt with a near total blackout in the mainstream media, and a lack of official statement or narrative from the UK Labour Party.

Fast-forward one year, and a palpable sense of disillusionment has permeated the air as we bear witness to the continued erosion of Labour’s foothold in Tower Hamlets. Indeed, upon speaking with residents and stakeholders, it has become clear that Mayor Lutfur Rahman and his Aspire Party have consolidated their position, leaving the local Labour Party further marginalized and bereft of support.

“All of you guys (Labour) come and promise the usual, parks, rubbish, ASB etc. Then just deliver on some things, not all. He has come along and put money in my pocket (free school meals), of course, I’m going to vote for him again (Mayor Lutfur Rahman).”

Resident (May 2023)

The following piece is part of four-part long read pieces, looking at the reasons for defeat and the ongoing detachment of TH Labour, who constitute the official opposition in Tower Hamlets. The pieces will cover the following four themes:

- Not understanding migrant culture in the East End

- Not understanding the Muslim community in the East End

- Not understanding the impact of inequalities on working-class communities

- Structurally incapable of operating in a competitive political environment

This essay is one instalment of a four part examination into the multifaceted reasons for the electoral defeat of the Tower Hamlets Labour Party, as well as the ongoing sense of detachment that has continued to plague this organisation. As the official opposition, the Labour Party’s continued failures and missteps have raised serious questions about their relevance and efficacy within the local political landscape. Through a comprehensive analysis of the factors that contributed to their downfall, we can begin to unpack the complex and nuanced issues that have led to their disarray. As well as possible pathways to regain the trust of residents in Tower Hamlets.

Let us kick off this series, by looking at Tower Hamlets Labour’s ham fisted approach towards migrant communities in the East End, in particular the Bangladeshi community.

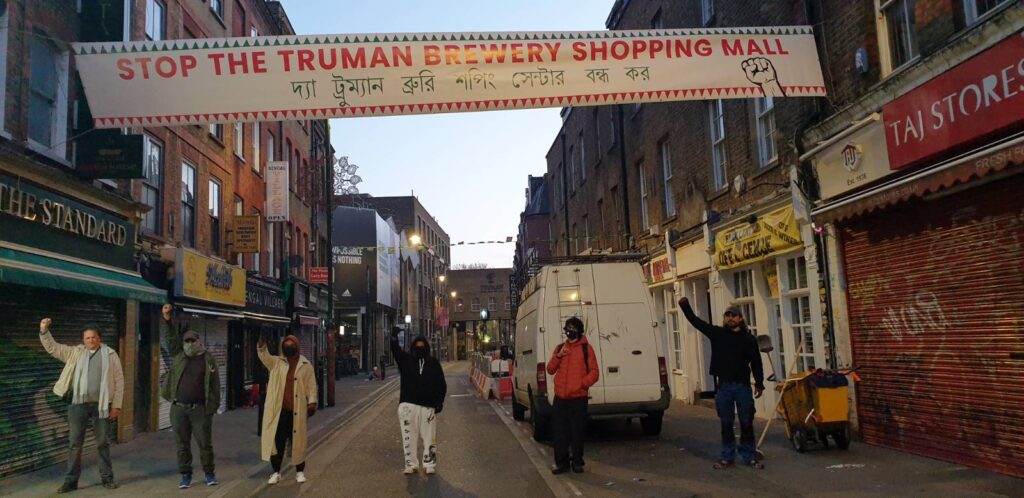

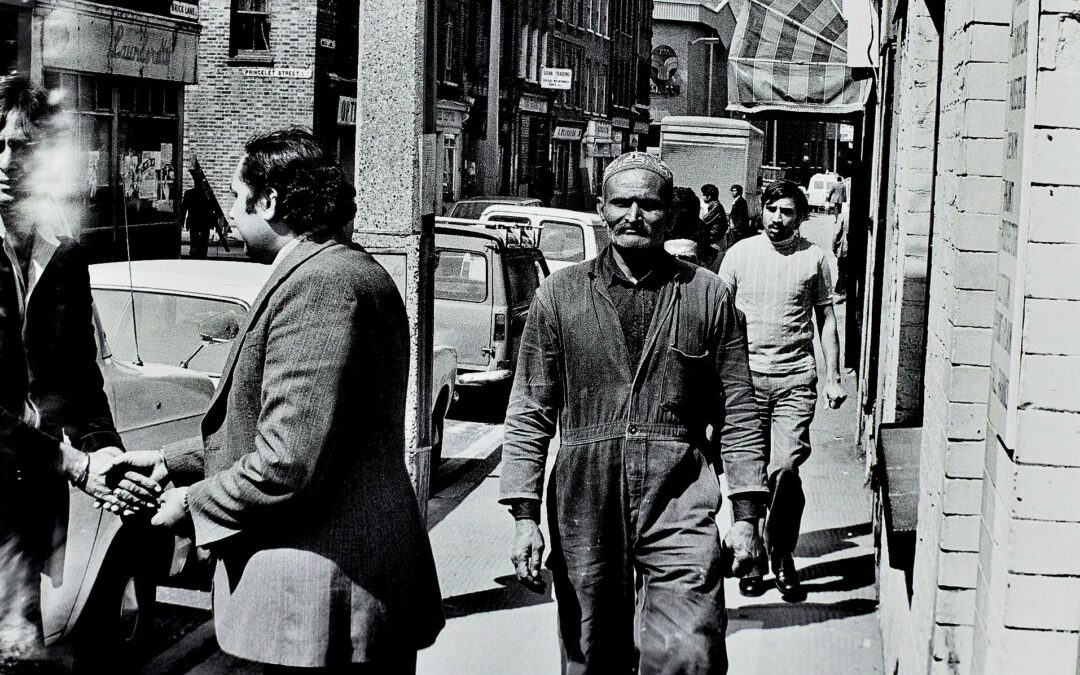

History of Migration in the East End

The East End of London is awash with the ebb and flow of human migration, a fact that is both storied and emblematic of the area. This rich tapestry of movement can be traced back six centuries, when the City of London guilds relegated polluting trades to the eastern fringes. Brick Lane, named for the brick kilns that once dotted the area, became a marginal space for those engaged in economic activities deemed unsavoury by the powers that be.

Yet from this inadvertent social experiment arose a haven for the marginalised and dispossessed, a place where migrants could forge new lives and communities. Across the centuries, a kaleidoscope of peoples have flocked to this space, drawn by the promise of economic prosperity or seeking refuge from persecution, or both.

The relationship between London and the Bangladeshi community spans over 400 years, back to the establishment of the East India Company.

From the refugees fleeing the Hundred Years’ War in France to German Hanse League merchants, from French Huguenots to Catholic Irish, from Jews of Eastern Europe to Bangladeshi Muslims who arrived in large numbers after the Second World War, the East End has been a beacon for those seeking a new start. And so the area continues to thrive as a testament to the enduring power of migration and the human spirit.

The undeniable ebb and flow of immigrant populations have forever enriched the cultural tapestry of London, imbuing the very fabric of the city with a vivid mosaic of diverse influences. From the tantalising infusion of exotic flavours into the local cuisine, to the subtle cadence of foreign phrases that pepper everyday language. However, despite this undeniable enrichment, the relationship between certain immigrant groups and the local political establishment has been fraught with difficulties. The Tower Hamlets Labour Party, for instance, has had a particularly chequered history in this regard.

Before the Second World War, the Jewish community, encountering barriers to entry into the local Labour Party, opted to join en masse the Communist Party, which proved to be a powerful force in organising the momentous Battle of Cable Street. In fact, it was through this mechanism that the last Jewish Communist MP, Phil Piratin, was elected.

In the decades following the war, the Bangladeshi community followed a similar path, voting in independent councillors in the 1980s in order to force the local Labour Party to open its doors to their participation. The relationship since has been a rocky one, marked by a series of ups and downs. As we fast-forward to the present day, the political landscape of Tower Hamlets reveals a curious paradox. In the year 2022, the bulk of the migrant community, in alliance with embedded working-class communities, decisively rejected the local Labour Party led by John Biggs and instead, cast their votes in favour of Lutfur Rahman and his Aspire Party, which swept to a majority in the Council Chamber and secured the Mayoralty.

This outcome begs the question: despite the advances made in accommodating minorities and marginalized groups within the national Labour Party, why does the local party in Tower Hamlets face hostility from migrant communities and find itself rejected at the polls? Drawing on a rich tapestry of conversations, personal experiences, and current academic literature, I will attempt to unravel this intriguing paradox that has confounded political observers and journalists alike.

Common Misunderstandings: Exclusion of the Migrant Experience from Our Arts

An anecdote, narrated by a Bangladeshi artist friend of mine, illustrates the gulf of understanding between the local Labour Party and the migrant community it purports to represent. The Bangladeshi artist recently found himself in the company of a long-standing Tower Hamlets Labour councillor. As they engaged in conversation about art and culture, the councillor made a presumptuous comment, “Oh, you must be from India, not Bangladesh.” Illustrating the trope that Bangladeshi’s are incapable of producing culture, that all South Asian cultural production emanates from India via Bollywood.

This exchange is not only indicative of the attitudes prevalent amongst the leadership of the local Labour Party, but is also reflective of the wider biases held by social managers of public and cultural institutions in Tower Hamlets. Moreover, such biases are reflected in some of the council policies of the borough. The underlying assumption is that migrant communities and their cultures are regressive and have nothing of value to contribute either universally or to the broader London culture. This entrenched view is founded on three fundamental axioms:

Firstly, it is believed that migrants hail from societies that are inherently backward. Secondly, their cultural traditions are seen as stagnant, with no capacity to evolve or offer anything of relevance to other demographics or the wider society. Lastly, migrant contributions to the public discourse are not recognised nor acknowledged, but are instead pigeonholed in a set designated marginal space.

A case study of the Town Hall

Whilst serving as an elected councillor at Tower Hamlets Council, I chanced upon such an attitude. It became apparent that the Mayor, through the council, had the power to bestow a plethora of appointments to an array of institutions throughout the locale, from housing association boards and quangos to arts and cultural bodies. However, upon further scrutiny, I discovered a peculiar trend; no appointments to the aforementioned arts and cultural institutions had been extended to councillors from a Bangladeshi background. Despite representing nearly a third of the borough, no appointments were made in 2018 to any of the arts and cultural bodies, depriving them of Bangladeshi background representation:

- Create London

- English Heritage Historic Environment Champion

- Rich Mix Cultural Foundation

- V&A Museum of Childhood

- Whitechapel Art Gallery

- Women’s Environmental Network

- Lee Valley Regional Park Authority

- Norton Folgate Almshouse Charities

In light of the fact that a significant portion of the populace self-identify as from a Bangladeshi background, I voiced my concerns over this overt exclusionary practice. Regrettably, my requests for an explanation were met with a lacklustre response. With hindsight, I should have known that this attitude was prevalent throughout the borough, that Bangladeshi’s don’t get Art. As this attitude was replicated in my interaction with a local arts institution.

A case study of the Rich Mix Centre

A good case study to look at in terms of the exclusion of the migrant experience from the Arts is the Rich Mix Centre. A complex with over five floors, containing a three-screen cinema, and flexible performance spaces. The Rich Mix also houses 20 creative organisations. However, in the council estates amongst working-class communities, there is resentment towards the institution. In particular, the Bangladeshi community.

Here, one finds oneself grappling with the profound weight of alienation and resentment. These emotions, nuanced and multifaceted as they are, often find themselves misapprehended and grossly misrepresented by the very cultural institutions purporting to understand and engage with them. In the case of the Rich Mix, an institutional inability to understand such resentment. Such a disheartening realisation, came to me one fateful day as I, a Councillor when received a distressing telephone call from the Rich Mix Centre.

The telephone call came around the same time I was working with the artist Abbas Zahedi in Brick Lane, this encounter left an indelible impression upon my consciousness. The voice on the other end of the line, infused with a palpable sense of anxiety, lamented the alleged hostility harboured by the Bangladeshi community towards the Rich Mix Centre, attributed unjustly to the figure of Lutfur Rahman. A familiar chord was struck within me, as I recognized the echoes of a pernicious racist trope that has been regrettably pervasive throughout recent Tower Hamlets history: “They are all Lutfur Rahmans.”

I carried on giving a sympathetic ear, and finished the conversation, saying it is more complicated than that, explaining the issue of how the Bangladeshi community feels excluded from that space. A space subsidised with millions of pounds, while vital services such as the Nafas, a Drug Rehabilitation service catered towards the BAME community, were dismantled by Tower Hamlets Council. Alas, I never received another phone call.

Such a world-view creates an environment where migrant communities feel alienated and unwelcome in public institutions, and in response, seek to substitute or even replace them entirely. Spilling over to the political arena. When the Whitechapel Councillor, Shahed Ali was imprisoned in 2016. In the following by-election, residents rejected the local Labour Party by voting for an independent councillor, a local driving instructor, Shafi Ahmed. When I spoke to a group of residents, from the Berner Estate in Whitechapel, why they voted for Shafi and not Tower Hamlets Labour, I received the following reply:

Bruv, you see they locked up Shahed Ali because of Rich Mix. They shut down Nafas and at the same time gave a million pounds to Rich Mix. Shahed was the only person who spoke out. To punish him, Biggs did the case on him and put him in prison.

Shahed Ali was a political prisoner. He is like Nelson Mandela, spoke out against racist decisions, and they put him in prison. When he came out of prison, we were celebrating. Just like they celebrated when Mandela came out.

Whitechapel Resident from the Berner Estate in 2017

This spill over was repeated with the landslide defeat of Labour by the Aspire Party in 2022. And again, instead of learning from the lessons, Tower Hamlets Labour Group are advocating more funding for the Rich Mix Centre. With a narrative, I have been informed, that Bangladeshis don’t understand the value of avant-garde culture. However, the veracity of these assumptions must be questioned. Are migrant societies truly backwards and undeveloped? Is their culture really as static as is believed?

These are crucial questions that demand careful consideration, and a nuanced understanding of the realities that migrants face. Until then, our cultural institutions will continue to be impoverished, deprived of the enriching contributions of diverse communities. And a feeling of hostility and alienation will continue to exist.

Migrants & Modernity: Introducing the Bengal Renaissance & the Bhadralok

Revisiting Our Assumptions About Modernity

Modernity refers to the historical period beginning in the late 18th century and characterized by a series of profound cultural, economic, and social changes. It is often associated with the rise of industrialization, urbanization, and the emergence of new forms of political organization.

The modern changes as opposed to traditional ways of living have profoundly impacted virtually every aspect of human life, from how we work and communicate to our understanding of ourselves and our place in the world. It continues to shape the course of human history and remains a subject of ongoing debate and analysis in fields such as philosophy, sociology, and cultural studies.

From my experience as a Tower Hamlets Councillor, in the halls of power, a pervasive belief persists that the gateway to modernity for East End migrants is the arrivals terminal at Heathrow Airport. This notion, is deeply entrenched in traditional historiography on the background of recent migrant communities. An attitude promulgated in popular culture by such modern luminaries as Nial Ferguson, who conflates, in his book Empire, the advancement of modern medicine with the spread of colonialism.

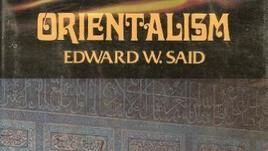

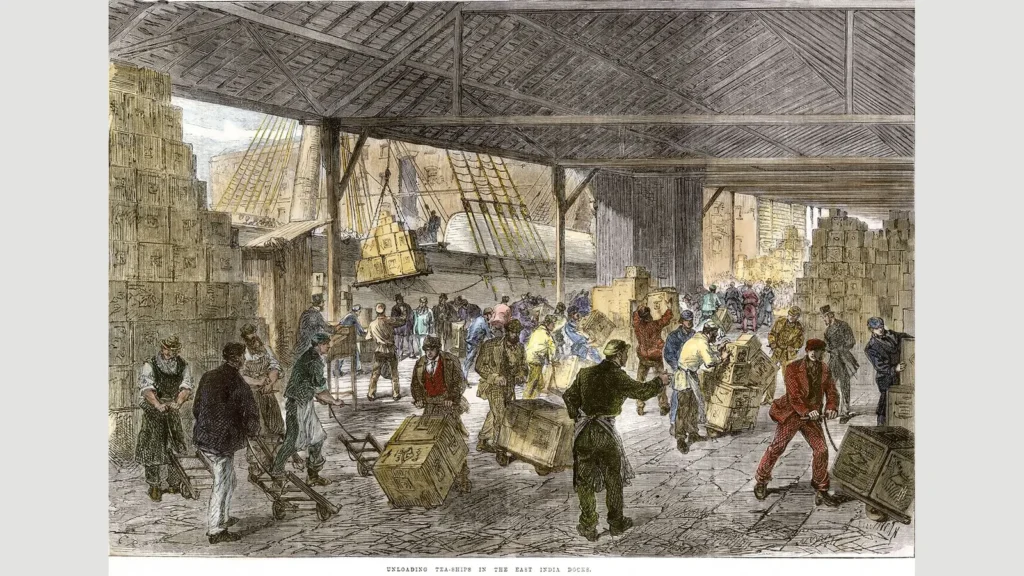

Starting in the 1960s, this received wisdom in Western academia has been challenged by historians such as Marshall Hodgson, continued by Edward Said and others, whose rigorous research has undermined the assumptions of the past. Recent historical research has revealed that Bengal enjoyed a trade surplus with the United Kingdom well into the first quarter of the 19th century. This stands as a direct contradiction to the prevailing narrative of Bengal as a stagnant backwater. The research exposes the destructive policies of early Victorian Britain, which actively worked to deindustrialize Bengal in order to bolster the textile industry in Lancashire, in order to appease powerful electoral interests.

The empirical facts laid bare by such scholarship thus pose a vexing question: if Bengal was not a backwater, as so many have assumed, then what was really happening there? The answer, no doubt, lies in a more nuanced understanding of the complex interplay between economics, politics, and culture, and the legacy of colonialism that has shaped our world.

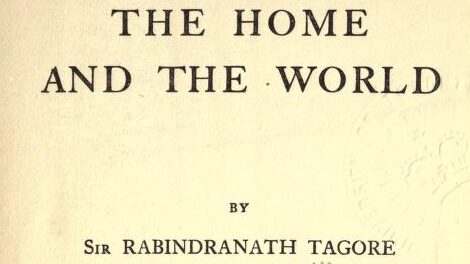

Home and the World: The Bengal Renaissance

Modernity arrived in Bengal through global trade. However, with the military takeover by the East India Company in 1757, a complex interplay of colonial dominance and anti-imperial resistance, remoulded this modernity into a new cultural expression, a renaissance. The Bengal Renaissance was a cultural and intellectual movement that swept across the Bengal region of the Indian subcontinent in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Defined by a rekindled interest in the region’s history, language, literature, and art, the Renaissance was driven by a dynamic and educated middle class.

At the heart of the Bengal Renaissance were towering figures such as Raja Ram Mohan Roy, Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, and Rabindranath Tagore. Roy, a polymath and social reformer, agitated for a wide range of progressive causes, including women’s rights and the abolition of the caste system. Vidyasagar, a tireless advocate for education and social reform, campaigned for the education of women and the elimination of child marriage. Tagore, a prodigious polymath and artistic visionary, was a prolific writer, poet, and painter. In 1913, he became the first non-European to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.

The Bengal Renaissance was also marked by a flourishing of Bengali literature, which focused on contemporary social issues and emphasized the use of vernacular language. This literary flowering was closely linked to the broader social and intellectual ferment of the period.

Art was another domain in which the Bengal Renaissance made its presence felt. The Bengal School of Art emerged as a new style that blended traditional Indian techniques with Western artistic concepts, creating a distinctive and visually arresting aesthetic. The work of artists such as Abanindranath Tagore, Nandalal Bose, and Gaganendranath Tagore captured the imagination of both Bengali and international audiences.

In the annals of political history, the Muslim League’s establishment in Dhaka and the land reform movements stood out as the definitive embodiment of political aspirations. This momentum eventually led to the coronation of AK Fazlul Haq as the premier of pre-independence united Bengal. At the heart of this cultural upsurge was the bhadralok, an influential middle-class community. So who are these Bhadraloks?

Introducing the Bhadralok: The Purveyor of Modernity and Culture in Bengal

The etymology of the term “Bhadralok” traces its origins to the Sanskrit word “Bhadra,” which encompasses a range of values, including property, particularly in the context of homesteads. The specific homestead property granted to an individual without rental obligations was known as “bhadrasan.” Consequently, the occupant of such a property came to be referred to as “bhadra,” leading to the derivation of the term “bhadralok.” Over time, this expression began to denote individuals who exhibited refined behaviour and manners.

The phrase gained prominence during the era of the East India Company and, more significantly, during the period of direct British Crown Rule (1858-1947). It came to represent a burgeoning middle class in Bengal, primarily referring to Hindus, while the term “Ashraf” was employed for Muslims. However, as Indian nationalism gained momentum, both designations gradually merged, and by the early 20th century, “Bhadralok” became an inclusive term encompassing both Hindus and Muslims.

The members of the Bhadralok class assumed leadership roles in the nationalist movement that emerged in the late 19th century. Up until the second decade of the 20th century, this privileged class held a pre-eminent position in Bengal’s administration, economy, and political spheres. Their education and outlook commanded widespread respect within society. However, with the expansion of the suffrage and the implementation of land reforms from the 1920s onwards, the Bhadralok class experienced a decline in their political and economic dominance. Nevertheless, they managed to preserve their cultural influence, a position they continue to hold in high culture to this day.

With globalisation, and the increase in urbanisation, pockets of this Bhadralok world can still be found in the old neighbourhoods of the provincial or Mufassil towns in Bangladesh, but more generally in the villages that make up modern Bangladesh. I was fortunate as a child to experience this world of the Bhadralok.

‘Heimat’ – ‘My’ Home and the World: Childhood Experience of Bhadralok Culture in Bangladesh

During my childhood, a prolonged stay in Bangladesh afforded me an immersive encounter with the Bhadralok culture, encapsulating a rich tapestry of experiences. From witnessing my uncle in his capacity as the local rural mayor, Chairman of the Union, presiding over diverse meetings held within the very walls of our ancestral home, which doubled as a local Town Hall. To delve into the intricacies of the six seasonal variations, agricultural land management, animal husbandry, and the diverse strains of rice cultivation. Engaging in leisurely pursuits such as fishing, embarking on wildfowl hunts accompanied by rifles, and partaking in field sports became cherished pastimes.

However, not every moment was steeped in leisure and pleasure. At the behest of my mother, I was subjected to a rigorous weekday educational routine. At the crack of dawn, I would receive religious instruction from a seminary student who found lodging within our familial abode. Following a swift breakfast, I would make my way to the local school to immerse myself in the realm of Bangla medium education. After the school day drew to a close, a brief interlude for lunch and a siesta ensued. The late afternoon until dusk was dedicated to leisure, whether indulging in field sports, embarking on trips to the local market, or simply just chilling. As twilight descended, private tutoring sessions commenced, conducted by a diverse array of mentors, ranging from a government civil servant who resided under our roof. Interspersed by a cadre of local teachers, each specialized in their respective subjects.

This carefully crafted regimen bestowed upon me a plethora of experiences. Notably, my knowledge of Hinduism sprang from the erudition of the Hindu Brahmin Head Teacher and the presence of Hindu families interwoven into the fabric of our village. The profound respect and mutual understanding demonstrated by these distinct communities stood in stark contrast to the prevailing narrative of perennial animosity that we are told in the United Kingdom. Such interactions fostered within me a profound comprehension of the Hindu faith as practised among Bengalis, revealing its monotheistic essence—a striking departure from the teachings I encountered in my British schooling.

Yet, amidst the luminosity of this Bhadralok culture, a shadowy aspect also emerged. It entailed a rigid social hierarchy, bolstered by practices and circumstances that perpetuated these divisions. The tumultuous realm of Bengal street politics laid bare its violent nature. My inaugural encounter with an election unfolded against a backdrop of armed military personnel swarming our village and its surroundings during my uncle’s bid for re-election. I bore witness to chilling eyewitness accounts of the associated violence and horrors. Following on from the elections, this experience also included the tragic annihilation of an entire family and a brazen assassination attempt on my uncle and our own family.

The inflexible nature of these social norms chafed at the time, unknown to me, against my inner anarchist. Reflecting upon these experiences, one cannot help but draw parallels to the Ancien Régime of pre-Revolutionary France, immortalized within the annals of history. As a mischievous child, imbued with the spirit of Peter Pan, I defied these norms whenever possible—expressing dissent against prevailing practices and undermining hierarchical structures. Eventually, communal complaints were lodged against me. Yet, my father stood by my side, politely dismissing these grievances.

At the gathering, the complainants branded me a Communist agitator, igniting within me a fervent curiosity to delve into the meaning of this term. As the adage goes, the rest is history—a journey of exploration and discovery that commenced with that initial encounter, shaping my world view in ways unforeseen.

The Bhadralok in Britain

It was the Bhadralok who spearheaded the migration to Britain from Bengal now modern-day Bangladesh and West Bengal. They were from a class that could migrate, due to access to land and other liquid assets. Underscoring the non-financialised nature of the economy at the time. During the days of Empire, they answered the call to be sailors for an expanding merchant navy. Many gave their lives during both world wars. Locally in Tower Hamlets, this could be seen at the memorial at St Annes Church in Limehouse, where one of the first names etched, is the name, Abbas.

Post-Second World War, they again answered the call, this time to meet the Labour shortage to rebuild a war-shattered Britain. With access to capital, they paid for their passage to join the working-class communities in the East End and other industrial towns and cities that proliferated in post-war Britain. Through their laborious efforts, the Bhadralok left an indelible mark on the socio-economic fabric of Britain’s society. But what about their impact on our cultural fabric?

“There are three Bengals. East Bengal, modern day Bangladesh. West Bengal. And then there is Brick Lane.”

Retired Tower Hamlets Councillor, Abdul Mukit Chunu OBE

Bhadralok Impact on the East End: Introducing Creolisation as a Framework of Understanding

Undoubtedly, the Bhadralok have left an indelible mark on the cultural tapestry of Britain. Their influence can be traced back to the era of the East India Company, evident in the adoption of words such as “Nabob,” “purdah,” and “curry” into the English lexicon. Even cockney rhyming slangs, like the phrases “shufti with the mufti” and “Ruby Murray,” bear the imprint of this cultural exchange. Today, the Modern Indian Restaurant, predominantly managed and operated by Bangladeshi entrepreneurs, stands as an emblem of the British High Street.

Yet, what of their impact in less apparent guises? By discarding the antiquated notion of migrant culture as static and fossilized, and embracing the dynamic nature that characterizes contemporary British culture, a question emerges: has the cultural production of the Bhadralok undergone a process of Creolisation, assimilating into the broader fabric of London’s cultural landscape?

Originally coined by linguists to elucidate the transformation of contact languages into creole languages, the term “Creolisation” has now found application in various social sciences to describe novel cultural expressions engendered by interactions between societies and uprooted communities.

Renowned sociologist Robin Cohen, whose scholarship covers the fields of globalization, migration, and diaspora studies, posits that Creolisation occurs when “participants selectively appropriate specific elements from incoming or inherited cultures, imbue them with divergent meanings, distinct from their original contexts, and ultimately merge them in a creative fashion to mould new varieties that supplant pre-existing forms.”

In the realm of cultural amalgamation, an astute gaze uncovers the telltale signs of Creolisation, which permeate various facets of contemporary society. Embodied in diverse art forms. Ranging from the resonant melodies of The Asian Dub Foundation to the contemporary English literature, found in Tony White’s, ‘Foxy T’, and even extending to fashion trends of the present era. This fusion of influences is palpable. Perhaps nowhere is it more manifest than in the labyrinthine realm of the ubiquitous social media platform, TikTok, where an assortment of videos brimming with the creative offspring of this cultural cross-pollination flourish.

However, it is an intriguing anomaly that amidst the rhetoric of the vibrant tapestry in Tower Hamlets Council, where I served as a Labour councillor, there exists a noticeable absence of any reference to this distinctive Creolised landscape. Curiously, the same void reverberates within the corridors of the Tower Hamlets Labour Party. Perusing the council’s extensive array of documents, policies, and proclamations, I found the glaring omission of even a solitary mention. This peculiarity assumes an added layer of intrigue when one takes into account the fact that our borough boasts one of the most youthful populations in the entire nation.

One cannot help but ponder the underlying causes of this inexplicable oversight. Could it be that our public institutions remain entrenched in an outdated political paradigm, where the tenets of cultural dynamism and diversity fail to find fertile ground? Such an inquiry opens Pandora’s box of conjecture, leading us down a meandering path of introspection. Perhaps the prevailing political ethos of our esteemed institutions, rooted in antiquated sensibilities, serves as an impediment?

Tackling Common Misconceptions: Arguments for Integration & Arguments Against Assimilation

In contemplating this pervasive myopia, a barrier to understanding, exhibited by our public institutions, cultural managers, and decision-makers with regard to Creolisation in Tower Hamlets. One cannot help but direct attention across the English Channel. France, is a nation, boasting one of the largest migrant populations in all of Western Europe. Yet, paradoxically, the French state has chosen to shun the principles of multiculturalism, opting instead for an assimilationist policy that has had far-reaching repercussions. The repercussions, to be precise, have materialized in the form of widespread alienation experienced by migrant communities, subsequently impinging upon crucial socio-economic indicators, including a disproportionate representation within the prison system. Additionally, this flawed policy has birthed a deeply flawed political arena, allowing for the ominous resurgence of far-right ideologies.

In light of this disconcerting reality, it is worth examining the proposals put forth by Jean Luc Mélenchon, a prominent left-wing candidate for the French presidency. Mélenchon has astutely advanced the concept of Creolisation as a robust analytical framework for comprehending the intricate tapestry of modern French society. By advocating for the adoption of this framework, Mélenchon seeks to effectuate a transformative shift within public and cultural institutions, rendering them more accessible and nurturing a society that is cohesive and empathetic in nature. Crucially, embracing Creolisation offers a powerful antidote to the affliction of alienation that plagues migrant communities, while concurrently providing a comprehensive framework for integration that effectively counters the pernicious narratives of “National Populism” propagated by the far right.

It is evident, then, that the inherently flawed nature of assimilationist policies has been laid bare not only within the context of France but also in other geopolitical domains. We need only cast our gaze towards the People’s Republic of China, wherein tensions between the state and marginalized ethnic groups such as the Tibetans and Uighurs are palpable. Similarly, the Republic of Turkey finds itself embroiled in a disconcerting dynamic vis-à-vis the Kurdish population. The repercussions of assimilationist policies are manifest and manifold, and their inherent failures loom large, serving only to exacerbate existing conflicts and ignite new ones.

Returning to the local arena of Tower Hamlets, it becomes apparent that the Council and its affiliated arts and cultural institutions have inadvertently adopted an assimilationist framework, in stark contrast to their obligations under the Public Sector Equalities Duty enshrined within the Equality Act. This misalignment must not be allowed to persist unchallenged.

To rectify this disconcerting state of affairs, a judicious course of action lies in the implementation of a series of comprehensive audits. These audits ought to employ the most recent census data as the foundational benchmark, functioning within the statutory framework provided by the Equality Act. Through these audits, an in-depth review of council policies and outcomes becomes possible, alongside an examination of the policies and outcomes of the institutions that the Council funds and exerts influence over through appointments.

The imperative to rectify this insidious myopia cannot be overstated. It is through such concerted efforts, buttressed by an unswerving commitment to equality and inclusivity, that our public institutions, cultural managers, and decision-makers can begin to dismantle the prevailing status quo of alienation and resentment. A good example of assimilationist policies not working, and creating a backlash, is the recent election defeat in 2022 of the Tower Hamlets Labour Party.

Assimilation does not work: A Case Study of the Tower Hamlets Labour Party

An inadvertent assimilationist paradigm permeates the Tower Hamlets Labour Party, and its repercussions manifest in the othering of migrant communities, casting them as static and fossilized entities. This phenomenon becomes evident through the superficial appropriation of their cultural symbols, wherein fetishization takes precedence over understanding. Regrettably, we find ourselves bearing witness to yet another instance of this disconcerting trend, as exemplified by the local Labour Party’s recent obsession with the hijab, the headscarf. Astonishingly, the saga continues, I have been informed, with the obtuse association drawn between South Asian men sporting long beards and an ill-conceived notion that such token gestures would translate into substantial political gains.

However, it becomes increasingly apparent that such totemistic appropriation fails to resonate with the local electorate, particularly those who identify as Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic (BAME). A compelling illustration of this sentiment was recently recounted to me during a conversation with a resident of Mile End. Engaged in a spirited discussion, this individual passionately recounted their encounter with Mayor John Biggs during the 2022 London Marathon, a crucial juncture leading up to the elections. Their contention was clear: the Labour Party faced an imminent peril of losing the election, and they attributed this predicament to various factors. Notably, they emphasized the fetishization of symbols associated with migrant communities, highlighting the futility of such gestures in generating additional votes.

In this thought-provoking exchange, the Mile End resident cogently conveyed their dissatisfaction with the prevailing political landscape, defying the shallow assumptions that underpin tokenistic gestures. Mayor Biggs, in response, offered a nod of recognition, acknowledging the validity of their perspective with a measured phrase, “I see you have a point.”

This encounter epitomizes a broader narrative, where the inauthentic assimilation of migrant communities through surface-level appropriations and the disregard for substantive policies only serves to alienate rather than engage. The pitfalls of this assimilationist paradigm are illuminated through conversations that draw attention to the disjuncture between performative politics and the pressing concerns of a diverse electorate. If political actors are genuinely committed to effecting change and securing the trust of marginalized communities, they must transcend the superficial and embrace substantive policies that address the multifaceted realities of those they seek to represent.

So where does that leave the Tower Hamlets Labour Party?

So Where are the Bhadralok with Tower Hamlets Labour? ভদ্রলোক কোথায় ?

To comprehend the present state of affairs within the Tower Hamlets Labour Party concerning its relationship with the Bangladeshi community, one must turn to the Bhadralok. The Bhadralok, in sociological parlance, act as the social and cultural custodians of the Bangladeshi migrant population. In their characteristically discreet manner, they wield control over strategic situations, with the true power lying not in the vociferous voices that dominate gatherings, but in the quiet ones that shape the deliberations.

Bhadralok: Do you know what is the meaning of politics?

Me: To get things done?

Bhadralok: No, to get things done, without asking for it.

Conversation with a Bhadralok in the East End, 2017

Tower Hamlets Labour and the Problem of the native misinformant: Political and functional illiteracy

The Tower Hamlets Labour Party consistently commits a grave error by erroneously identifying what we, in the realm of Trade Union organizing, refer to as the “natural leaders” within the Bangladeshi community. Instead of diligently assessing influential figures through a comprehensive process known as a “structure test”, which measures an individual’s social capital within their community, they opt for the individuals with the loudest voices. Here, the term “community” is broadly defined to encompass various factors such as economic sector, geographic area, protected characteristics, or a combination thereof.

Regrettably, this persistent fallacy in discernment is further exacerbated by the relentless pursuit of personal gain, where the allure of allowances and alleged kickbacks within the realm of being a local councillor. This has fostered the emergence of a semi-permanent economic and political elite within the Tower Hamlets Labour Party. These individuals, as described by a former Deputy Leader of Tower Hamlets Council, are those who have failed to secure employment elsewhere and consequently view the Council as a mere job and a source of income.

As a consequence, we witness a local Labour leadership that is ill-informed, lacking the requisite technical expertise required to effectively govern a multibillion-pound organization like the Tower Hamlets Council. The repercussions of this deficiency are far-reaching, as it permeates the very core of the council’s operations, hindering its ability to function optimally and fulfil its responsibilities to the community it serves. Feeding into a vicious cycle of resentment and alienation towards the local Labour Party, not just by the Bangladeshi community, but communities and individuals from all demographics. An unusual coalition, agreeing upon the consensus, that the Tower Hamlets Labour Party is a basket case, and is simply non-functional as a political institution.

The Bhadralok Approach to Tower Hamlets Labour

The Bhadralok’s regard for the current leadership or group of councillors within the Tower Hamlets Labour Party is far from favourable. Frankly speaking, it never has been. They perceive the Party as a hostile entity to be manipulated as per their needs. Consequently, they have replaced their allegiance with Mayor Lutfur Rahman and the Aspire Party. This same disposition extends to the publicly funded cultural institutions in Tower Hamlets. Rather than patiently awaiting or demanding access to these institutions, they have chosen to hold cultural events and gatherings in various restaurants, cafés, and community centres.

The Bhadralok disposition towards the Tower Hamlets Labour Party and its leadership can be aptly characterized as an overt exhibition of disinterest, reflective of their typical Bhadralok manner. This perspective becomes readily apparent through a conversation I had in 2021 after my announcement of not seeking re-election. The topic of the conversation was a declaration made to the then Mayor, John Biggs, by a Councillor, then came to be known in various circles:

“He declares to Biggs that we, as ageing gentlemen situated in Redbridge and Barking, are in the twilight of our political influence. He further proclaims that he and his ‘Syndicate’ represent the vanguard of the future, and will win the election for him. Such utterances, regardless of their falsehood, flow forth from his lips without restraint.

We invite them (Biggs and his team) to our familial gatherings and communal feasts, thereby offering a glimpse into our ethos of conviviality and openness. We willingly share our sustenance and extend our hospitality, creating an environment where bonds are fostered.

They never extend the courtesy of inviting us into their homes, sharing their food, or introducing us to their families. But we will continue to invite them. We don’t need them, they need us. And we are better than them.”

Conversations with a Bhadralok in the East End, 2021

Breaking Ranks with the Bhadralok?

আমি চির-বিদ্রোহী বীর –

বিশ্ব ছাড়ায়ে উঠিয়াছি একা চির-উন্নত শির!

“I’m the eternal Rebel, I have risen beyond this world, alone, with my head ever held high!”

Bidrohi (Rebel) by Kazi Nozrul Islam

On this matter, I hold a differing opinion from the prevailing Bhadralok consensus in the East End. I choose the way of the poet Nozrul, and his archetype #Bidrohi, ‘The Rebel’. I believe that change for the better is possible if we actively strive for it, both within our public cultural and arts institutions and within the Labour Party itself. There must be a way out of this vicious cycle of alienation and animosity, and we need to find it. To illustrate my point and instil hope, I offer an example.

In December 2020, I penned an article for a political magazine, advocating for the Labour Party to adopt comprehensive codes of conduct that address not only Islamophobia but all forms of discrimination against marginalized liberation groups. Upon sharing the draft of this article with a fellow Muslim Labour Party member, news broke regarding the exposure of anti-black and Islamophobic social media posts by Labour donor and member David Abrahams. In response, my colleague chuckled and remarked, “They have yet to issue a public statement regarding David Abrahams, and you believe they would consider your proposal? Keep dreaming!

Yet, against all expectations, they did. #KhelaHobe

“ বাইরে থেকে বর্গী আসে — Raiders come from outside,

নিয়ম করে প্রতি মাসে – Attacking us on a regular basis,

আমিও আছি, তুমিও রবে – This time I’ll be there, and you’ll be there,

বন্ধু এবার খেলা হবে – Friend, we will give you the game of your life,

খেলা খেলা খেলা হবে – Bring it on, Game On! “

Khela Hobe ! — Popular Bengal Street Political Chant

FURTHER READING – On Bengali Bhadralok/Bengal Renaissance culture

1 – The Autobiography of an Unknown Indian by Nirad C Choudhury

2 – A Story of Ambivalent Modernization in Bangladesh and West Bengal: The Rise and Fall of Bengali Elitism in South Asia by Pranab Chatterjee.

3 – The Bengal Renaissance by Subrata Dasgupta

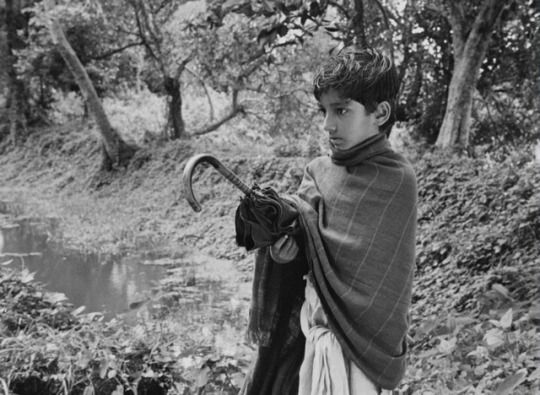

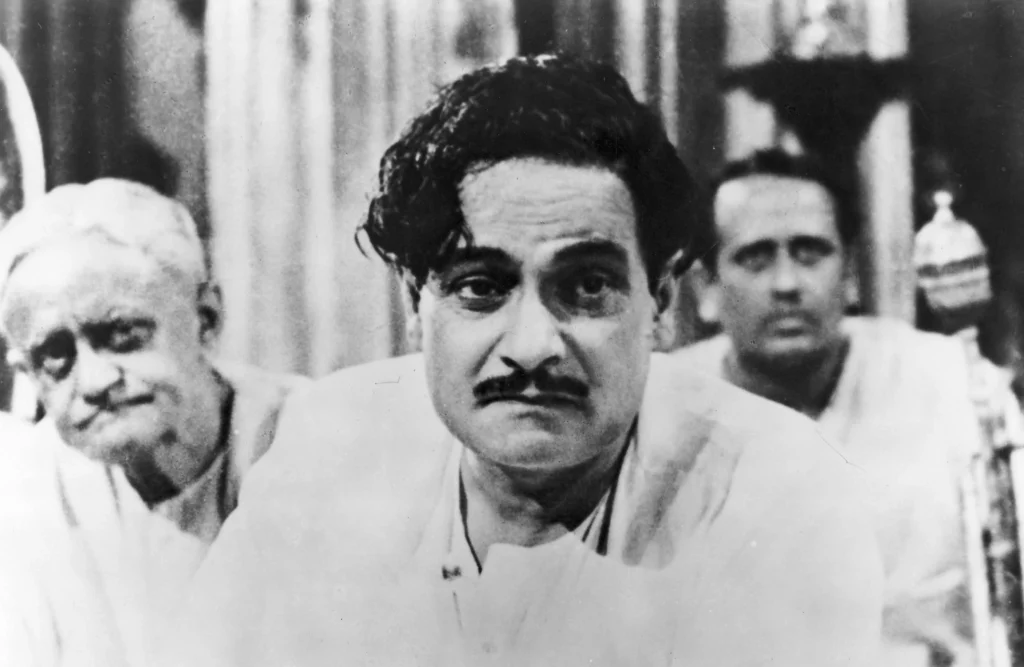

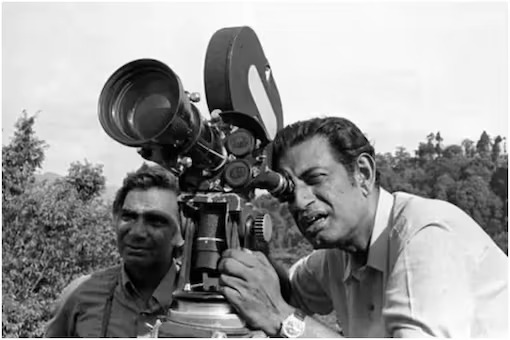

Visual Essay on Bengali Bhadralok Culture – Jalsaghar (The Music Room) by Satyajit Ray, 1958

Widely regarded as one of the greatest films of all time. Voted #20 on the list of “100 Best Films” by the prominent French magazine Cahiers du cinéma in 2008. Was ranked at #27, #146 and #183, respectively, in the Sight and Sound list of Greatest Films in 1992, 2002 and 2012. The British Film Institute included it in their list of ‘360 Classics’.

Summary

Jalsaghar (Bengali: জলসাঘর Jalsāghar, lit. ’The Music Room’) is a 1958 Indian Bengali drama film written and directed by Satyajit Ray, based on a popular short story by Bengali writer Tarasankar Bandyopadhyay, and starring Chhabi Biswas.

In addition to discussing the perennial themes of the meaning, function and production of art and culture. The film summarises the inherent tension in Bhadralok culture, This is the tale of a zamidar (Feudal Lord) who has nothing left but respect and sacrifices his family and wealth trying to retain it.

Essay by film critic Roger Ebert on ‘The Music Room’

Music

The movie is a tribute to the wide genres in music, from Hindu Sanskrit motifs at one end to Muslim Persianate motifs at the other end, with all the variations and spectrum in between. Demonstrating the wide influences in terms of the Bengal Renaissance.

Music and dance performed onscreen – Begum Akhtar, Roshan Kumari, Waheed Khan, Bismillah Khan, and company;

Music performed offscreen – Daksinamohan Thakur, Asish Kumar, Robin Majumdar, Imrat Hussain Khan;

FURTHER READING – On Creolisation of Migrant Culture in the East End and Contributing to the Richness of the Common London Culture (Modern Cockney)

2 – ‘Evolution of Cockney in 50 objects’ by the Modern Cockney Festival, 2023 by Saif Osmani

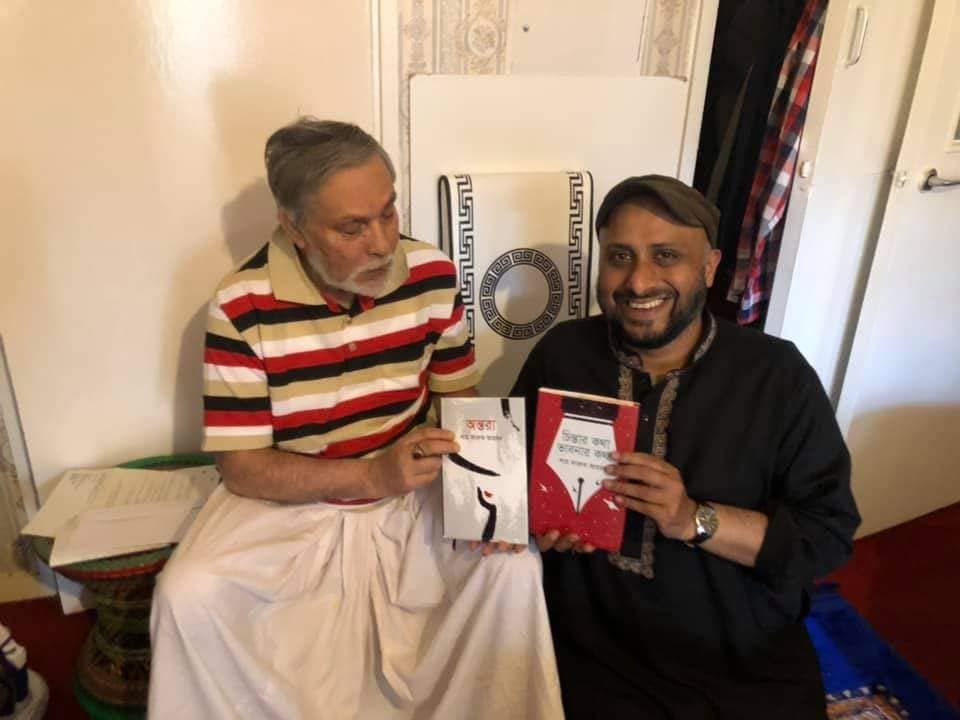

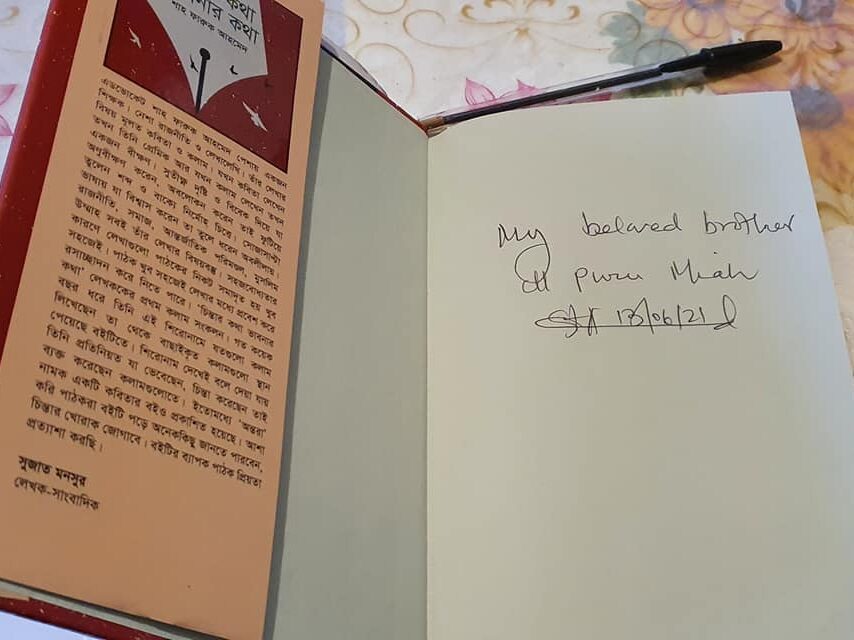

4. – ‘Brick Lane Foundation’ by Abbas Zahedi, Old Police Station, Spitalfields & Banglatown, London, 2021 – Site-specific installation for Nocturnal Creatures art festival in collaboration with Tower Hamlets Councillor Puru Miah and Whitechapel Gallery

5. – Working Class & Cockney: Breaking Down Prejudice & Exclusion by Puru Miah

6 – ‘We Stand With Palestine’ Solidarity Wall by Puru Miah, Brick Lane, May 2021 – Site Specific installation in collaboration with Zak Hussain and the Sisters Forum.

Recent Comments