LONG READ – PART 3 OF FOUR PARTS (PART 1 AND PART 2 CAN BE READ HERE): An exploration into the recent 2022 defeat of Labour in Tower Hamlets. In particular, why the party is seen with hostility by members of the Working Class Community? Exploring the dynamics of the misinformed view of the Working Class community has left to a loss of support and electoral defeat for Tower Hamlets Labour.

A leadership of the Tower Hamlets Labour Party, which was hung up with a baseless notion of, they will all move to Essex, about working-class residents. A lack of understanding about the effects of inequality, culminated in the pursuit of the ill-informed policy of Liveable Streets. Resulting in widespread rejection by working-class communities and an electoral wipeout in 2022.

Divided into 9 parts with case studies and references:

- Regime Change: One Year On

- A History of the Working Classes in the East End

- Match Girls Strike of 1888

- Dockers’ Strike of 1889

- Battle of Cable Street in 1936

- Bengali Housing Action Group (BHAG) 1976

- It’s the Inequality Stupid!: How do you solve a problem like poverty?

- Tower Hamlets Labour and the Undeserving Poor?: Condescension and Contempt for Working Class Residents?

- The Politics of Hope: When Politicians Delivered Dreams

- Case Study of the Politics of Hope in the Global South

- Case Study of Labour Led Islington Council and its Fairness Commission

- Case Study of Mayor Lutfur Rahman and the Universalism of Free School Meals

- The Days of Tower Hamlets Labour: The Politics of Fear or When Politicians Claim To Protect Us From Imagined Nightmares

- The Politics of Fear: Exploitation of Insecurities

- Case Study of Tower Hamlets Labour and the Campaign to Save the Community Language Service

- The Politics of Fear: Emotional Appeals

- Case Study of Tower Hamlets Labour and the Spitalfields and Banglatown Neighbourhood Plan and Forum

- The Politics of Fear: Otherisation and Scapegoating

- Case Study of Tower Hamlets Labour and Shamima Begum

- The Politics of Fear: Law and Order Rhetoric – Protection from Impending Peril

- The Politics of Fear: Manipulation of Information

- Case Study of the Tower Hamlets Labour Political Strap Line: It’s Either Us or the Commissioners Will Take Over.

- The People vs Tower Hamlets Labour: The Case of Liveable Streets (Low Traffic Neighbourhoods)

- The Tower Hamlets Labour Logical Fallacy: “I’m from a working-class background, how can I be detached from working-class realities.”

- Introducing the World of Logical Fallacies

- Introducing the World of Material Conditioning

- Introducing Tower Hamlets Labour’s Material Facts

- Tower Hamlets Labour: A political party or a rent-seeking vehicle for local cartels?

- What is Political Rent-Seeking?

- A Tribute to Michael Young: 70 Years On, Reflections from “Family and Kinship in East London”.

“There is power in a factory, power in the land

There Is Power in a Union – Billy Bragg

Power in the hand of the worker”

Regime Change: One Year On

Following the stunning electoral upset of the Aspire Party of Mayor Lutfur Rahman in Tower Hamlets, Labour suffered a devastating blow that reverberated throughout the political landscape. A reverberation still felt with a near total blackout in the mainstream media and a lack of official statement or narrative from the UK Labour Party.

Fast-forward one year, and a palpable sense of disillusionment has permeated the air as we bear witness to the continued erosion of Labour’s foothold in Tower Hamlets. Indeed, upon speaking with residents and stakeholders, it has become clear that Mayor Lutfur Rahman and his Aspire Party have consolidated their position, leaving the local Labour Party further marginalized and bereft of support.

“All of you guys (Labour) come and promise the usual, parks, rubbish, ASB etc. Then just deliver on some things, not all. He has come along and put money in my pocket (free school meals), of course, I’m going to vote for him again (Mayor Lutfur Rahman).”

Resident (May 2023)

The following piece is part of four-part long read pieces, looking at the reasons for defeat and the ongoing detachment of TH Labour, who constitute the official opposition in Tower Hamlets. The pieces will cover the following four themes:

- Not understanding migrant culture in the East End

- Not understanding the Muslim community in the East End

- Not understanding the impact of inequalities on working-class communities

- Structurally incapable of operating in a competitive political environment

This essay is one instalment of a four-part examination into the multifaceted reasons for the electoral defeat of the Tower Hamlets Labour Party, as well as the ongoing sense of detachment that has continued to plague this organisation. As the official opposition, the Labour Party’s continued failures and missteps have raised serious questions about their relevance and efficacy within the local political landscape. Through a comprehensive analysis of the factors that contributed to their downfall, we can begin to unpack the complex and nuanced issues that have led to their disarray. As well as possible pathways to regain the trust of residents in Tower Hamlets.

Let us kick off the third in this series, by looking at Tower Hamlets Labour’s ‘contempt’ towards the working class concerns and a total disconnect from the impact of inequalities that afflict the working class communities.

A History of the Working Classes in the East End

“Now the lessons of the past

There Is Power in a Union – Billy Bragg

Were all learned with workers’ blood”

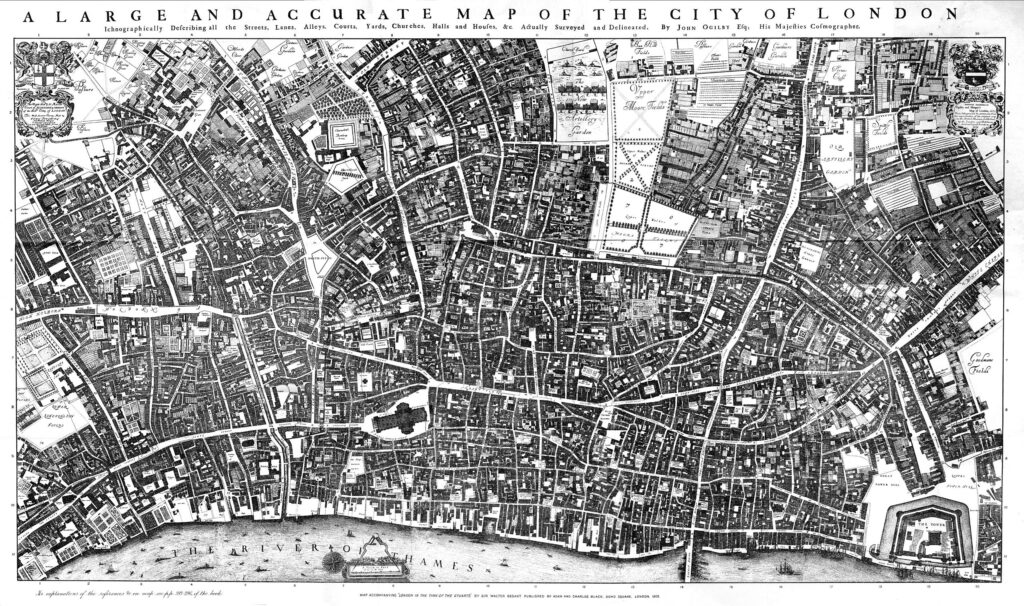

In the annals of the City of London’s historical tapestry, one finds an intriguing tale of the medieval civic fathers’ audacious environmental experiment. These astute minds, seeking to mitigate the noxious fumes and miasma plaguing their bustling metropolis, conceived a remarkable plan. Harnessing the prevailing westerly winds, they strategically relegated all polluting trades to the eastern fringes of the city, a region now known as Brick Lane owing to its proximity to the City Gate. Little did they anticipate that this ingenious stratagem would inadvertently spawn a social experiment, carving out intentional spaces for marginalized communities and their marginal economic pursuits.

These communities, hailing from both local shores and distant lands, harboured aspirations of a better life for all. In an era preceding modernity, they would have been labelled “Sans-culottes,” a French expression denoting the common folk of the lower echelons, distinguished by their lack of breeches—a moniker that aptly captured their social standing. As the winds of industrialization swept across the nation, these communities metamorphosed into the working class, laying the foundations for what would be known, in contemporary parlance, as the East End.

Indeed, the struggles endured by the working class in East London, United Kingdom, over the course of centuries, weave a tapestry rich in both triumph and tribulation. A crucible of industrialization, urbanization, and the attendant challenges faced by the toiling masses, East London has borne witness to the dramatic unfolding of this history.

The winds of change blew forcefully during the late 18th and early 19th centuries as the Industrial Revolution ushered in a paradigm shift in East London. A torrent of industrial enterprises, including textiles, shipbuilding, and bustling docks, transformed the landscape, attracting an influx of labourers to the region. However, the rewards of this industrial fervour were accompanied by the burdensome yoke of harsh working conditions, interminable hours, paltry remuneration, and abject living standards that befell the working-class denizens of East London.

In response to this unforgiving crucible, the labourers of East London began to unite and form trade unions, assuming a formidable collective voice. The burgeoning trade union movement in the late 19th and early 20th centuries provided a crucial platform for these workers to mount a valiant struggle for equitable working conditions, just wages, and enhanced rights, both within and beyond the confines of the workplace. Organized communities boldly confronted landlords, demanding improved housing conditions. Strikes and labour disputes became the order of the day as the indomitable spirit of the working class found expression through collective action, amplifying their grievances and asserting their rightful demands.

Amongst the annals of the working class struggles, the following occurred in the 19th and 20th centuries:

Match Girls Strike of 1888

The Match Girls’ Strike in East London occurred in 1888 when young women and girls working at the Bryant and May Match factory protested against harsh conditions and low wages. Around 1,400 match girls went on strike, demanding improved working conditions, higher pay, the end of white phosphorous usage, and the right to form a union. With support from activists and media coverage, the strike gained public sympathy, leading to a significant victory after two weeks. Bryant and May agreed to their demands, raising wages, improving conditions, and abolishing white phosphorous use. The strike’s success shed light on workers’ rights and inspired future labour movements, leaving a lasting impact on social and political changes.

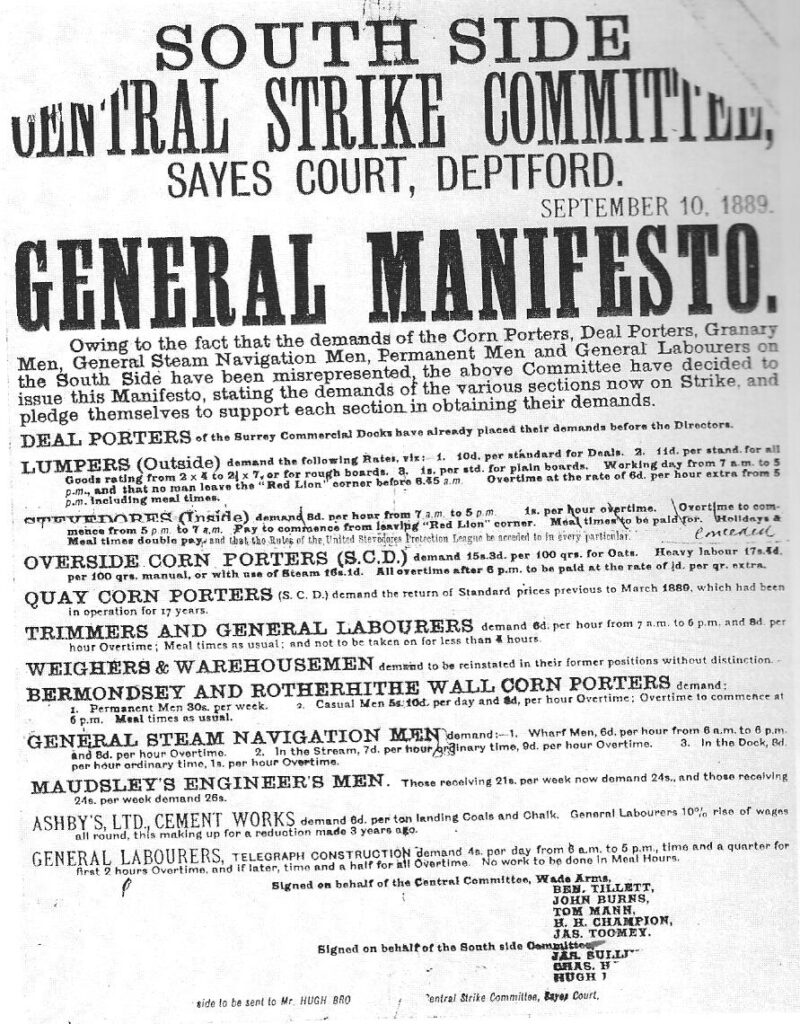

Dockers’ Strike of 1889

One of the most significant working class struggles in East London was the Dockers’ Strike of 1889. The strike involved thousands of dockworkers who protested against low pay and precarious working conditions. Led by trade unionist Ben Tillett, the strike successfully secured a minimum wage and improved conditions for dockworkers, setting a precedent for future labour movements.

Battle of Cable Street in 1936

During the 1930s, East London became a hotbed of political and social tensions, particularly around issues of fascism and anti-Semitism. In response to a planned march by the British Union of Fascists (BUF) through the area, a massive demonstration known as the Battle of Cable Street took place. Working-class residents, along with Jewish and immigrant communities, joined forces to block the fascist march, leading to clashes with the police. The events of Cable Street are considered a pivotal moment in the fight against fascism and a symbol of East London’s working-class solidarity.

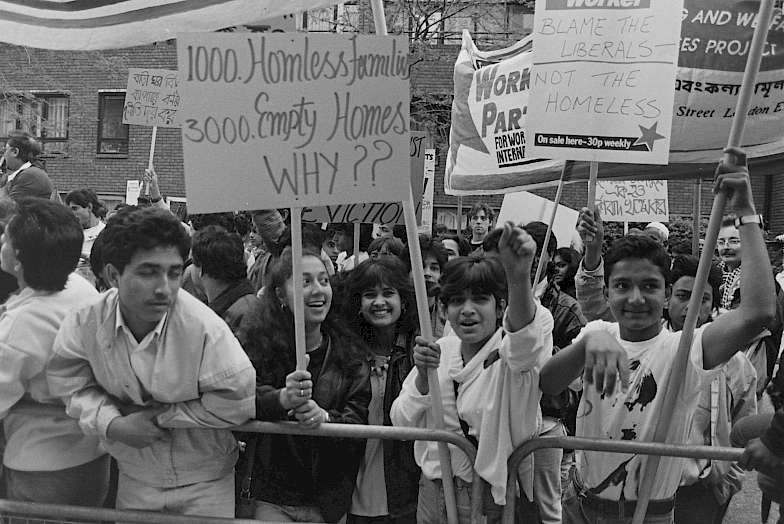

Bengali Housing Action Group (BHAG) 1976

The squatters’ movement by the Bangladeshi community in East London emerged as a response to the housing crisis and discrimination faced by the community. Facing inadequate housing and a shortage of affordable options, some Bangladeshi immigrants resorted to squatting as a means of securing shelter. Activists organized themselves into collectives, occupied vacant buildings, and engaged in protests and demonstrations to draw attention to their precarious living conditions and advocate for better housing rights. Their efforts have contributed to raising awareness about the housing crisis in East London, influencing housing policies, and addressing the specific housing needs of the Bangladeshi community.

The chronicles of East London’s working-class struggles stand as a testament to the indelible legacy of perseverance and resilience. Their stories illuminate the intricate interplay between industrial progress, societal transformation, and the ceaseless pursuit of social justice. As we traverse the contemporary urban landscape, let us not forget the struggles and sacrifices borne by those who toiled in the crucible of the East End, forever etching their indomitable spirit into the annals of history.

Amidst the winds of change that have swept through our society, heralding an era of industrialization, universal suffrage, and the establishment of a post-war welfare state, one might have expected a gradual erosion of inequality and poverty. Yet, against all odds, these enduring scourges have refused to dissipate. In recent times, their grip has tightened, even within the confines of Tower Hamlets, an enclave renowned as the third-wealthiest borough in England, its coffers brimming with a staggering per capita wealth generation exceeding £100,000. It is a confounding paradox that, in the face of such opulence, more than half of the borough’s children find themselves ensnared by the cruel clutches of food poverty, a plight that eclipses the abysmal national average by threefold. This disturbing reality prompts a pressing question: why, in an era seemingly marked by the reduction of absolute poverty, does the relentless spectre of inequality continue to command our attention?

It’s the Inequality Stupid!: How do you solve a problem like poverty?

“The Union forever defending our rights

There Is Power in a Union – Billy Bragg

Down with the blackleg, all workers unite”

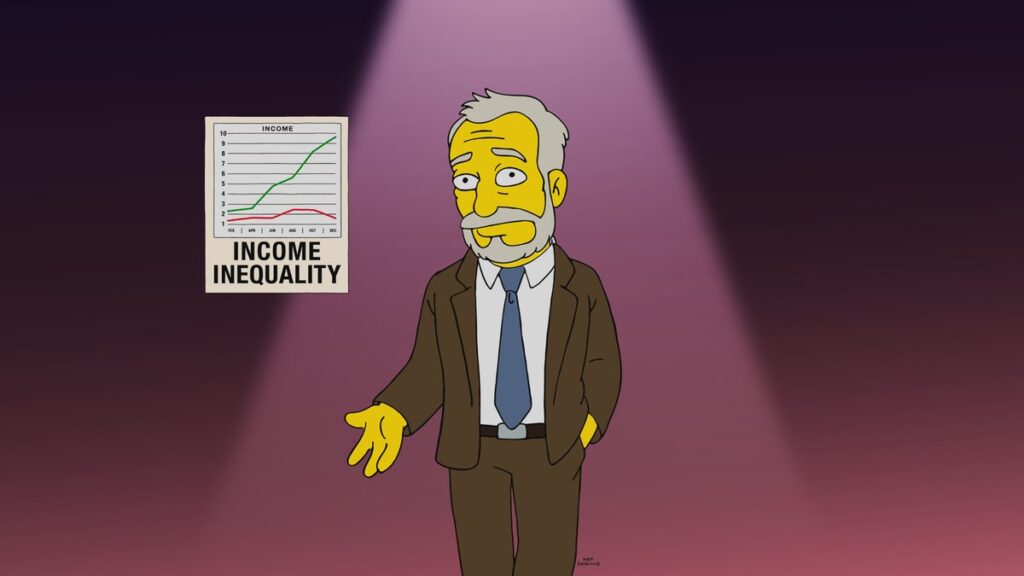

In 2009, academics Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett wrote their seminal work, “The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better”. It explores the relationship between income inequality and various social problems in different countries around the world.

The book’s central argument is that societies with greater income inequality tend to have worse outcomes across a range of measures, including health, education, crime, social mobility, and overall well-being. Wilkinson and Pickett argue that these negative outcomes are not only confined to the poorest members of society, but also affect the majority of the population, including those in the middle class.

The authors support their argument with extensive data and statistical analysis, drawing on a wide range of sources. They present evidence from various countries, showing that societies with a smaller gap between the rich and the poor have better overall social outcomes. They argue that income inequality creates a sense of social hierarchy and status anxiety, leading to increased stress, lower trust, and less social cohesion.

Wilkinson and Pickett also discuss the negative impact of income inequality on health, noting that unequal societies tend to have higher rates of physical and mental health problems. They suggest that the stress and anxiety associated with living in a more unequal society contribute to these health disparities.

Additionally, the book addresses the potential causes and solutions to income inequality. The authors argue that policies aimed at reducing income inequality, such as progressive taxation, minimum wage laws, and access to quality education and healthcare, can lead to improved social outcomes and overall well-being.

“The Spirit Level” sparked considerable debate and discussion upon its publication. It challenged conventional beliefs about economic growth and suggested that income inequality has significant social consequences. The book continues to be influential in shaping discussions about inequality, social policy, and the pursuit of a more equal society. The argument has been further picked up and refined by Rutger Bregman, in his “Utopia for Realists And How We Can Get There”.

So given that the Tower Hamlets Labour Party, professes to give political representation to working-class communities, reducing inequality will be its mission statement? Right?

“The natural distribution is neither just nor unjust; nor is it unjust that persons are born into society at some particular position. These are simply natural facts. What is just and unjust is the way that institutions deal with these facts.”

John Rawls – A Theory of Justice

Tower Hamlets Labour and the Undeserving Poor?: Condescension and Contempt for Working Class Residents?

“ A mother came to, complaining about the lack of amenities. I told her not to worry. A few years later, I found out that the family moved out to Essex. You see, problem solved.”

Tower Hamlets Labour Leader – In conversation with me before I was a councillor.

As I ventured into the realm of Tower Hamlets Labour as a Councillor, my expectations were imbued with a sense of idealism. I believed that the forefront of the administration would prioritize the representation of working-class communities, actively striving to diminish the prevailing inequalities in Tower Hamlets. This viewpoint, rooted in the conviction that poverty and inequality are not inherent and immutable realities, led me to anticipate a concerted effort to deconstruct these artificial constructs through well-crafted policies and unwavering political determination.

Regrettably, what I encountered was a prevailing culture of poverty management rather than reduction within the council. Instead of setting clear objectives for poverty alleviation programs, our focus seemed to rest solely on announcing the allocated funds without establishing clear Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). Consequently, money was spent on programs devoid of effective metrics for evaluation.

Furthermore, a lack of holistic thinking pervaded the council, resulting in policies that inadvertently exacerbated rather than alleviated inequalities. One such instance manifested in our planning department, where urban planning policies were implemented without considering their impact on impoverished families. This led to the displacement of these families from the City Fringe ‘Opportunity Area’, resulting in the closure of a Primary School and placing two others in imminent danger of meeting a similar fate.

Curiously, when engaging with the leadership of Tower Hamlets Labour or senior council officers, the notion of reducing inequality appeared to be conspicuously absent from our conversations. This oversight is particularly concerning considering the precarious financial situation of Tower Hamlets Council, where the structural deficit, equivalent to our Council Tax Reduction Scheme (CTRS), persists as a pressing concern. It would seem prudent for us to actively pursue objectives aimed at lifting people out of poverty. At the same time, reducing reliance on the CTRS, thereby creating a dual advantage of increased income through council tax and a decreased Council Tax Benefit bill.

Coming from a working-class background, I couldn’t help but detect a subtle undercurrent of contempt towards residents of similar backgrounds emanating from the Tower Hamlets Labour leadership. Poverty and inequality were treated as cultural issues, with the implicit solution being the displacement of working-class communities from the area. Giving up on the political goal of improving the lot of working-class communities.

In light of these disconcerting revelations, I find myself questioning whether my initial idealism was misplaced, or if this political landscape indeed embodies the prevailing norm. Is it customary for those in power to harbour a latent disdain for working-class communities, only to pay superficial homage to their concerns during the electoral season? These introspective inquiries persist as I grapple with the intricate web of complexities and contradictions that define the political terrain of Tower Hamlets. Is this a universal norm? Let’s have a look.

“I am not interested in managing poverty, I want to reduce it!”

In a conversation with then Labour Mayor, John Biggs. Expressing my frustrations about the approach of his administration.

The Politics of Hope: When Politicians Delivered Dreams

“Now I long for the morning that they realize

There Is Power in a Union – Billy Bragg

Brutality and unjust laws cannot defeat us”

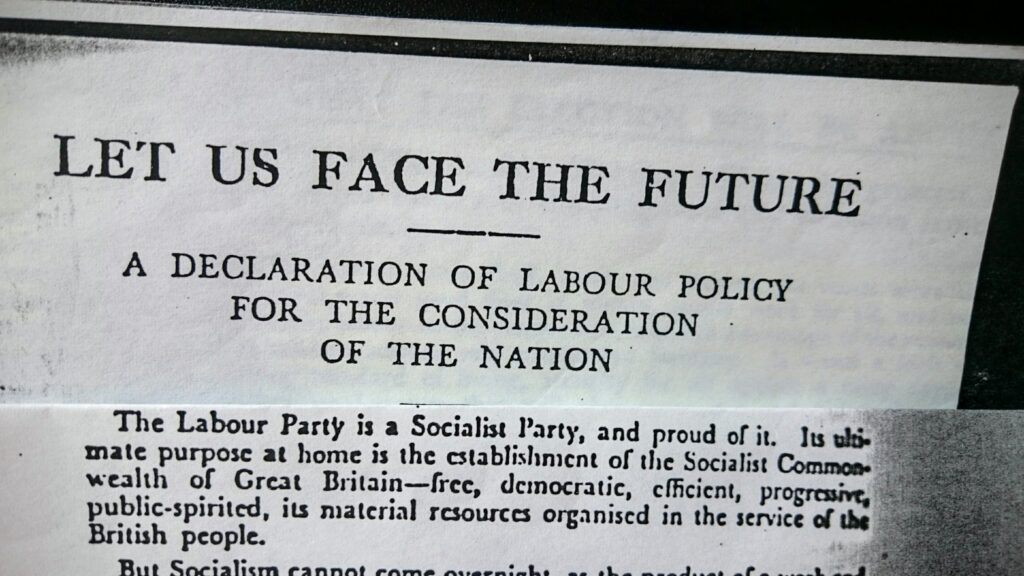

Once upon a time, politicians possessed the ability to captivate the masses with their grand visions, backed by meticulous research, tangible evidence, and an unwavering belief in the possibility of a better future. One shining example of this transformative leadership was the Labour government of 1945, led by Clement Atlee MP, a representative of the Tower Hamlets constituency in Limehouse.

During the historic 1945 general election, the Labour Party ascended to power in a resounding triumph, armed with a manifesto of profound consequence, aptly named “Let Us Face the Future.” The architect behind this influential document was none other than Michael Young, a British sociologist, social activist, and politician of multifaceted dimensions. Young is widely renowned for coining the term “meritocracy” and his diverse contributions as an academic researcher, polemicist, and institution-builder.

Throughout his illustrious career, Young spearheaded numerous initiatives in the realm of social reform, playing pivotal roles in the establishment of invaluable organizations. These notable endeavours encompassed the Consumers’ Association, Which? Magazine, the National Consumer Council, the Open University, the Institute for Community Studies, the National Extension College, the Open College of the Arts and Language Line, as well as a pioneering telephone-interpreting enterprise.

Young’s research and politics of empowering the working classes brought him to Tower Hamlets. In 1952, Young commenced his doctoral research at the prestigious London School of Economics, culminating in the completion of his thesis in 1955, titled “A Study of the Extended Family in East London.” This seminal work formed the foundation for his collaboration with Peter Wilmott on the seminal publication “Family and Kinship in East London.”

Within the pages of this book, Young provided a comprehensive sociological analysis of family and kinship structures prevalent in East London during the 1950s. Delving deep into the intricate dynamics of working-class communities, the study highlighted the paramount importance of extended family ties and shed light on the profound impact of societal changes on family life. Focusing specifically on the neighbourhood of Bethnal Green, renowned for its tight-knit communities and strong local identity, Young and Willmott conducted extensive interviews and surveys, unravelling the intricacies of family dynamics, marriage, and kinship bonds.

Regrettably, seventy-five years hence, the Labour Party of Tower Hamlets has forsaken the tenets of positive, homegrown politics, even failing to internalise the lessons derived from Young’s groundbreaking research in East London. As Young’s work espoused, working-class communities often rely on the support networks provided by extended families to mitigate the destructive impacts of poverty. This notable oversight would ultimately recoil upon Tower Hamlets Labour when the working-class populace rallied against the contentious Low Neighbourhood Scheme, known as Liveable Streets. An event I will cover in detail later.

Detractors may argue that this era of hopeful and affirmative politics is confined to a specific time and place, suggesting a need for realistic recalibration and progression. But one must pause and ponder: Is such a dismissal warranted?

Case Study of the Politics of Hope in the Global South

“With our brothers and our sisters

There Is Power in a Union – Billy Bragg

From many far off lands

There is power in a Union”

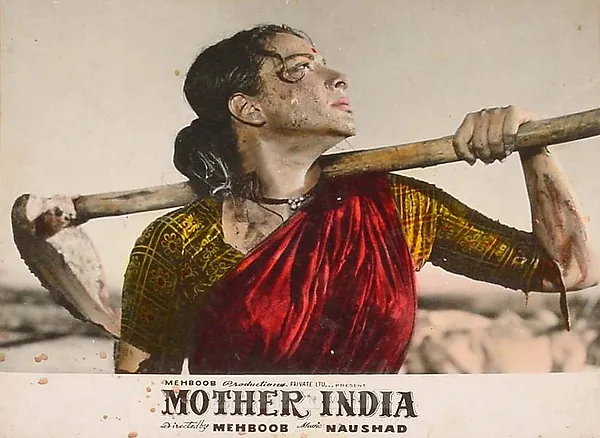

In previous posts, I wrote about my connections and experiences with the intricacies of politics within the Indian Subcontinent, with a particular focus on Bangladesh. Contrary to prevailing assumptions, my observations revealed a distinct absence of political disdain towards impoverished citizens, both in rural and urban settings. In fact, these individuals were exalted, along with a politics of hope, within the realm of culture, notably in poetry and cinema. A classic example is Mahboob Khan’s masterpiece, “Mother India,” a revered member of the illustrious Bollywood film canon.

This profound celebration of the underprivileged, and the betterment of society, resonated deeply within the political landscape following independence from the British Empire. A political consensus was established, to prioritise food security and eradicate the scourge of periodic famines that had plagued the region in the past. This ambitious vision materialised as the Green Revolution, an epoch characterized by significant technological advancements and agricultural practices spanning the 1940s to the late 1960s.

The Green Revolution, primarily aimed at augmenting agricultural productivity, engendered a boon for rural communities. Its implementation ushered in a period of unprecedented abundance and prosperity. For instance, my uncles, who served as rural mayors from the 1950s to the late 1980s, introduced High Yielding rice varieties into their localities, courtesy of the research conducted by the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in the Philippines. Remarkably, even today, Bangladesh stands tall as a self-sufficient nation in terms of cereals and proteins, despite the burgeoning population.

Shifting our gaze away from the realm of politics, it becomes evident that civil society too has witnessed a resolute drive to alleviate poverty. This concerted endeavour encompasses a range of initiatives, from the pioneering microcredit revolution spearheaded by Muhammad Yunus and the Grameen Bank, to the expansive cooperative model championed by BRAC, founded by Sir Fazle Abed. Notably, even the field of medicine has witnessed a notable push towards affordable healthcare, exemplified by the widespread adoption of generic medicines, a campaign galvanised by Zafarullah Chowdhury, founder of the ‘Gonoshasthaya Kendra’, a rural healthcare organisation.

In a broader context, it is intriguing to observe that the ardour to uplift the lives of the impoverished is not unique to the Indian Subcontinent but manifests itself throughout the Global South. But it also manifests closer to home, in fact in a Labour-led neighbouring council.

Let’s have a look.

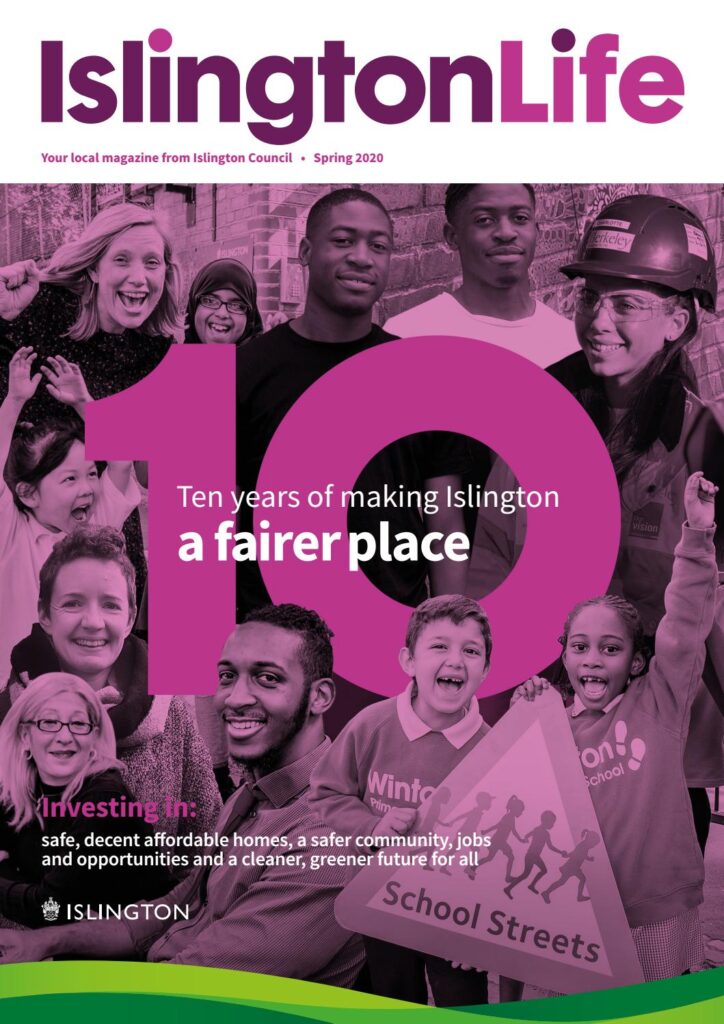

Case Study of Labour Led Islington Council and its Fairness Commission

“ Despite its wealthy image, Islington is the twenty-sixth most deprived local authority area in England, with extremes of rich and poor… The Islington Fairness Commission (IFC) was set up in June 2010 to look into how to make the borough a fairer place…”

Islington Council

In 2010, the Islington Council experienced a pivotal shift in power as the Labour Party assumed control from the Liberal Democrats. One of the party’s primary initiatives upon taking office was the establishment of a Fairness Commission, inspired by the influential work of Professor Richard Wilkinson, co-chair and author of The Spirit Level. Professor Wilkinson fervently espoused the belief that societal well-being is not solely contingent upon fairness but hinges on the attainment of greater equality.

After a year of diligent efforts, the commission published its recommendations, the majority of which were deemed achievable. Regrettably, it lacked the authority to enact a proposal that sought to curtail the operations of payday loan companies within the borough. Nevertheless, the ensuing two years witnessed a remarkable array of accomplishments, among them the celebrated reduction of £50,000 in the chief executive’s remuneration.

Yet perhaps even more striking was the transformative change in the council’s culture. Both officers and the bureaucratic apparatus were summoned to endorse the council’s political objective of fostering “a more equal future.” Every department was compelled to scrutinize its actions, pondering whether they served to exacerbate or alleviate inequality. Should the former prove true, mitigating measures were to be implemented. The planning department, for instance, arrived at a consensus on section 106 agreements, which granted the council control over ground-floor commercial units. These newfound acquisitions enabled the council to leverage such spaces in the pursuit of reducing inequality, such as by allocating them to social enterprises.

In stark contrast, we now turn our attention to the actions of Tower Hamlets Labour. Under the leadership of Mayor John Biggs from 2018 to 2022, a disheartening pattern emerged. Astonishingly, the very first act of Mayor Biggs’ administration was to grant councillors a pay increase. Moreover, several new positions were created, including a paid role for the Labour Group Whip and two additional Deputy Mayor positions, augmenting the existing statutory Deputy Mayor. Council records attest to my own dissent, alongside Cllr James King and Cllr Gabriela Salva.

This apparent lack of concern for addressing inequalities within Tower Hamlets created a political vacuum, leaving working-class communities adrift and disillusioned. Seizing the opportunity presented by this void, Mayor Lutfur Rahman and his Aspire Party emerged with a suite of measures designed to alleviate disparities in Tower Hamlets.

Case Study of Mayor Lutfur Rahman and the Universalism of Free School Meals

On the 4th of April 2017, Professor of Economics Diane Coyle, affiliated with the University of Manchester, authored a piece for the Financial Times. In her op-ed, she posited the merits of Universalism, specifically Universal Basic Services, as an effective tool for addressing the deep-seated issues of structural poverty and inequality. Universal Basic Services entail the provision of essential societal support to every individual, regardless of their financial means, ensuring their material well-being, enabling participation in community decision-making, and fostering opportunities for contribution. By expanding the social safety net to encompass these crucial components, the UBS model assumes a broader role within society.

Mayor Lutfur Rahman has astutely adopted this policy approach by instituting free and universal school meals, employing it as a means to combat disparities. Particularly within a London Borough where food poverty affects over half of all children, a staggering three times the national average. Through this endeavour, Mayor Rahman demonstrates a commitment to levelling the playing field and promoting equality.

However, a broader theme of universalism emerges, evident in the expansion of the Youth Service with the goal of establishing a centre in every ward. This commitment to universality extends further to encompass the voluntary sector, aspiring to broaden the reach of grants to as many recipient organisations as possible. Transcending the limited scope observed under Labour’s administration, where only a select dozen or so received such support.

However, the influence of universalism extends beyond the confines of Tower Hamlets or the tenure of Mayor Rahman. In the borough of Newham, under the leadership of Sir Robin Wales, universalism manifested in initiatives aimed at enriching the cultural experiences of working-class children, serving as a means to tackle inequality head-on. Programs such as ‘Every Child a Musician’ or ‘Every Child a Theatre Goer’ exemplify this dedication to providing equal opportunities to all.

In 2013, the Centre for Labour and Social Studies, in conjunction with the Jimmy Reid Foundation, published a policy paper entitled “The Case for Universalism: Assessing the Evidence.” This paper advocates for universalism as a superior alternative to selective approaches in social welfare systems. The authors contend that embracing selectivity exacerbates inequality, perpetuates the stigmatisation of beneficiaries, and diminishes participation. In contrast, universalism is hailed as a highly efficient approach, capable of delivering essential goods and public services that selective systems fail to provide. Moreover, it is argued that universalism has a greater economic impact, fostering stability and independence. Societies with robust universal welfare states are purported to be more successful, generating a progressive tax base, promoting gender equality, benefiting low-income groups paradoxically, and maintaining quality services. In contrast, selectivity is criticized for rejecting universalism, thereby associated with privatization and corporate profiteering that disproportionately affects the most vulnerable members of society.

Reflecting on my time as a Councillor in Tower Hamlets Labour, I am disheartened to note the absence of meaningful conversations surrounding universalism or a cohesive narrative centred on reducing inequality. Instead, the focus remained on fragmented micro-projects, with diminishing services outsourced to a select group of recipients. Tower Hamlets Labour failed to present a compelling vision or a unifying mission, leaving residents questioning the party’s capacity to wield power and shoulder responsibility. Regrettably, the narrative espoused by Tower Hamlets Labour revolved around fear-based politics, a disheartening deviation from a more uplifting trajectory aimed at progress and inclusivity.

With no optimistic vision being offered to working-class communities. Tower Hamlets Labour has confined itself when in power to the role of public managers, preserving the status quo. To restore their power and authority, instead of delivering dreams they divide the working-class communities, playing one group against another, promising to protect them from conjured nightmares. The politics of fear.

So what is this politics of fear?

The Days of Tower Hamlets Labour: The Politics of Fear or When Politicians Claim To Protect Us From Imagined Nightmares

“From the cities and the farmlands

There Is Power in a Union – Billy Bragg

To trenches full of mud

War’s always been the bosses’ way, sir”

The politics of fear, a term steeped in the Machiavellian playbook, serve as a critical lens to analyse the astute manoeuvrings of politicians and political factions. In our case, Tower Hamlets Labour. It delves into the intricate art of manipulating the collective psyche to garner support and exert control over working-class communities in Tower Hamlets. This strategic deployment of fear entails a multifaceted approach, encompassing various elements that intertwine to shape public perception. In my observations as a councillor observing the leadership of Tower Hamlets Labour, it broadly has five elements:

1. Exploitation of insecurities

2. Emotional appeals

3. Otherisation and scapegoating

4. Law and order rhetoric

5. Manipulation of information

The Politics of Fear: Exploitation of Insecurities

This political strategy is built upon exploiting existing insecurities within society, whether they are social, economic, or cultural in nature. Politicians adeptly identify these fault lines and manipulate them to instil profound fear among the masses. They utilize terrorism, crime, immigration, and economic instability as their chosen weapons, skillfully weaving a narrative that fuels anxiety and nurtures a craving for decisive leadership.

In the specific case of Tower Hamlets, working-class communities are deliberately divided into different groups based on ethnicities, such as White, Bangladeshi, Somali, and Black, and then set against one another. For instance, the Bangladeshi community may be pitted against the White working-class residents by labelling them as racists. Similarly, White working-class residents may be pitted against Bangladeshis by branding them as communal agitators.

For instance, during my initial engagement with the Liveable Streets campaigners in the summer of 2020, who resided in the northern part of the borough, a Labour councillor approached me and insinuated that they were all UKIP supporters, which is often used as a code word for racists. In response, I stated, “I don’t care. Moreover, I am here to represent all residents, not just the ones who vote for me.” As I interacted with the campaigners, I was pleasantly surprised to discover that many of them were lifelong Labour supporters, and some were even party members.

Case Study of Tower Hamlets Labour and the Campaign to Save the Community Language Service

Another example occurred in February 2020 when campaigners presented a petition with 5,000 signatures to save the Community Language Service, a program that taught languages including Spanish, Russian, Lithuanian, Mandarin, and Bengali. A Labour councillor stood up in the council chamber and accused them of all being Bengali communalists.

Communal politics refers to a form of politics that revolves around the interests and identities of particular religious, ethnic, or social groups within a society. It is a pretty big accusation with dog whistle connotations. It first came into prominence during the partition of the Indian Subcontinent in 1947, with violent connotations, resulting in up to 2 million deaths and 20 million refugees. Hardly a fitting description of a campaign where children presented the petition.

The Politics of Fear: Emotional Appeals

Yet, it is the realm of emotions where the true potency of fear resides. Politicians deftly ply their craft, employing skilful emotional appeals that sidestep rationality and strike at the very core of human vulnerability. Through vivid language, evocative imagery, and personal anecdotes, they tap into the primal wellspring of fear within individuals. Urgency and crisis become palpable, heightening public concern and engendering a receptiveness to policies promising security and protection.

Case Study of Tower Hamlets Labour and the Spitalfields and Banglatown Neighbourhood Plan and Forum

An interesting case study, of Tower Hamlets Labour and the politics of fear, centred in the Council Chamber. Is the debate and vote surrounding the Spitalfields and Banglatown Neighbourhood Plan and its forum. Tower Hamlets Labour, an organisation that aimed to be inclusive, had initially supported this initiative:

- The executive team included a third of members who self-identified as BAME (Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic), with a goal of achieving 50% BAME representation.

- The forum endorsed the eight principles of charitable and voluntary inclusiveness set forth by ACEVO (Association of Chief Executives of Voluntary Organisations).

- The forum was commended by an examiner for its efforts to engage with hard-to-reach demographics, collaborating with TELCO.

However, on the 5th of October, Tower Hamlets Labour took a stand against the plan. During the proceedings, there were speeches containing race-baiting rhetoric, accusing the forum of being similar to the National Front. Interestingly, Tower Hamlets Labour later voted in favour of the Roman Road Neighbourhood Plan, even though there was minimal BAME representation within that organization.

A Conservative councillor alleged that Tower Hamlets Labour was influenced by a developer lobbyist in the area. Intriguingly, upon further investigation, I discovered evidence of a more sinister plot. There seemed to be a deliberate effort to exploit racial divisions, orchestrated at the highest levels of Tower Hamlets Labour’s leadership. This included encouraging four Aspire councillors, including Ohid Ahmed (#Ohidgate), to defy Mayor Rahman and vote against the plan, in exchange for admission into the Labour Party.

This alleged manoeuvre, if successful, would have allowed Tower Hamlets Labour to shift its focus toward non-Bangladeshi residents, attempting to exploit a racially charged environment they themselves had created. Giving them an artificially constructed platform to portray the Aspire administration as a communal entity, playing on the fears of these residents in order to establish an electoral base and regain political power.

The unfolding narrative of the Spitalfields and Banglatown Neighbourhood Plan encapsulates a tapestry woven with ambition and the treacherous undercurrents of racial politics. Tower Hamlets Labour, with the strapline, One East End, now finds itself ensnared in a web of intrigue, casting a shadow of doubt over the very ideals it declares on its Twitter Account. As the chronicle unravels, one cannot help but contemplate the precarious nature of power and the depths to which individuals and organisations will descend in their relentless quest for political expediency.

The Politics of Fear: Otherisation and Scapegoating

In their Machiavellian artistry, practitioners of the politics of fear resort to a time-honoured technique: otherisation and scapegoating. By isolating and vilifying specific groups or individuals as the culprits behind perceived threats, politicians adroitly redirect fear and anger away from themselves or their policies. The result is a society riven by division and polarisation, each faction harbouring a collective animosity towards the chosen scapegoats.

Case Study of Tower Hamlets Labour and Shamima Begum

Shamima Begum, a name that has permeated headlines and ignited fierce public discourse, remains a subject of profound contemplation within British society. In 2015, the world bore witness to the story of this young British woman, a mere fifteen years of age. Groomed online and persuaded to leave her family in London, embarking upon a clandestine journey towards the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) in war-torn Syria.

Falling under the category of “jihadi bride,” Begum’s quest was aligned with a fervent devotion to the extremist ideology propagated by ISIS. In consort with two other adolescent girls from her school, she traversed borders and boundaries to establish residence under the draconian rule of the self-proclaimed caliphate.

In the ensuing years spent amidst the tumultuous landscape of Syria, Begum’s existence garnered international attention when a resourceful journalist encountered her in a refugee camp during the year 2019. To journalists, she revealed her yearning to return to her homeland, the United Kingdom. In response, the British government, deeming her presence a threat to national security, resorted to the revocation of her citizenship, effectively rendering her stateless.

Thus unfolded a narrative replete with intricate legal quandaries, ethical dilemmas, and profound questions concerning citizenship. Shamima Begum’s plight has precipitated an ardent and contentious debate, rife with fervent arguments and legal wrangling, as to the rights and responsibilities of individuals who choose to align themselves with extremist factions on foreign shores. In the case of Shamima being groomed when a child.

The story of Shamima Begum, though shrouded in the tenebrous depths of complexity, compels us to introspect upon our society’s response to radicalisation, the interplay of personal agency within the realm of extremism and child exploitation. The delicate balance between security imperatives and the principles of justice and compassion. In an era where our moral compasses are continually tested, her tale serves as a cautionary parable, urging us to interrogate the multifarious dilemmas that assail the modern world.

In the case of Tower Hamlets Labour there was no such understanding, instead playing to the gallery of othersisation, scapegoating to the mood music of fear-based politics. From an initial, “not a British Citizen”, to fumbling for a media message and procrastination in front of the media when more facts were revealed.

Further Reading: Shamima Begum and how Tower Hamlets Council failed us all.

The Politics of Fear: Law and Order Rhetoric – Protection from Impending Peril

Unsurprisingly, the rhetoric of law and order emerges as a staple in the politics of fear. Politicians, well-versed in the tides of public sentiment, amplify the clarion call for the restoration of order in the face of mounting fears. Here, in the context of Tower Hamlets, there is a slight twist. Tower Hamlets Labour leadership paints a war-torn borough, with various warring factions trying to take it over. From ‘White Van Angry Man’, ‘Nefarious Bengali Communal Politicians’, and ‘Crazy Long Bearded Muslims’ to believe it or not ‘Communist take over plots’.

The Communist takeover plot goes like this. Three Labour councillors walk into a pub off Roman Road, and declare that they are organising to stop a Communist takeover. I’ll let the reader fill in the rest of this carry-on comedy script, starring the leadership of Tower Hamlets Labour. Yeah, there are still people in the Tower Hamlets Labour leadership, fighting the 20th century Cold War, in 21st century Tower Hamlets.

With such a vivid picture painted, Tower Hamlet’s Labour leadership then position themselves as resolute leaders capable of shielding the public from the spectre of impending doom. Such a narrative resonates profoundly with those who seek solace in stability and long for the embrace of safety, or just want a quiet life.

The Politics of Fear: Manipulation of Information

Of equal concern is the deliberate manipulation of information woven into this intricate tapestry of fear. Politicians are adept in the politics of fear, selectively presenting or distorting facts to fortify the prevailing narrative of anxiety. By deploying hyperbole, misinformation, or outright propaganda, they foment a perpetual sense of danger and uncertainty. The consequence is an unwavering belief in the indispensability of their leadership as the bulwark against imminent peril.

In its totality, the politics of fear represents a calculated and cunning game, a subtle dance performed by politicians seeking to wield power. It revolves around the skilful manipulation of fear, employing emotional appeals, otherisation and scapegoating, law and order rhetoric, and the artifice of information manipulation.

However, the residents, particularly those from working-class communities in Tower Hamlets, have become increasingly aware of these strategies. This became evident during the Liveable Streets (Low Traffic Neighbourhood) debate, where 2,500 residents signed a petition alleging discrimination by the external contractors implementing the scheme. To their dismay, Tower Hamlet Labour councillors took turns scapegoating them, accusing them of denying climate change and even suggesting that they were indifferent to their own children’s well-being.

However, Tower Hamlets Labour persists in clinging to the politics of fear, despite its failure during the election campaign and its continued ineffectiveness afterwards. They continue to repeat the worn-out claim that “The commissioners are coming to remove Mayor Lutfur Rahman and Aspire,” as if it still holds any weight.

Case Study of the Tower Hamlets Labour Political Strap Line: It’s Either Us or the Commissioners Will Take Over.

In the field of advertising, the concept of a strapline has earned its place as a formidable weapon wielded by brands to etch their identity into the collective consciousness. The Oxford University Reference Dictionary elucidates that a strapline entails a pithy and indelible slogan that becomes intrinsically entwined with a specific brand. Countless examples spring to mind, such as Orange’s evocative proclamation, “The future’s bright, the future’s Orange,” BT’s affable invitation to converse, “It’s good to talk,” or L’Oreal’s empowering assertion, “Because you’re worth it.”

Yet, within the competitive environment of election campaigning in Tower Hamlets, the unofficial strapline adopted by Tower Hamlets Labour appears bereft of positivity, thereby dampening its persuasive potential. At its core, this message revolves around the ominous notion that the ascendance of any entity other than Tower Hamlets Labour will pave the way for the intervention by central government, with the imposition of Commissioners. Regrettably, the leadership of Tower Hamlets Labour has failed to proffer any constructive overtures to working-class communities, opting instead to anchor its strategy in the tempestuous currents of negative campaigning.

Negative campaigning, though often employed with fervour and conviction, remains an enigmatic enigma that tantalises scholars and political practitioners alike. While numerous studies have scrutinised its efficacy, the enduring appeal of this combative approach to persuasion persists. The fundamental premise upon which negative campaigns hinge is the belief that the targeted electorate stands to lose considerably by casting their vote in favour of the opposing candidate. However, in the electoral milieu of Tower Hamlets, rife with entrenched inequalities and socioeconomic disparities, the prospects for a negative campaign revolving around the impending arrival of Commissioners seem decidedly tenuous.

The very essence of such an approach assumes a populace predisposed to view alternative leadership with trepidation and apprehension. Yet, within a borough where more than half of its children languish in households gripped by the clutches of food poverty, and where the mercurial Mayor Rahman captivates the masses with his populist brand of optimism. A campaign predicated upon dire warnings of Commissioners’ ascendancy is doomed to falter. This approach has failed to yield the desired results during the election campaign. And as the sands of time recede, Tower Hamlets Labour finds itself inexorably relinquishing ground to the populist force of Mayor Rahman and his Aspire party.

In this unfolding political landscape, it becomes evident that Tower Hamlets Labour must undertake a profound introspection, a reassessment of its campaign tactics, and a recalibration of its ideological compass. The relentless negativity that has characterized its modus operandi has proven insufficient to sway the hearts and minds of a disillusioned electorate yearning for substantive change. To overcome the resounding triumph of Mayor Rahman and his Aspire party, Tower Hamlets Labour must transcend the bounds of negativity, casting off the shackles that tether it to an ineffective and antiquated paradigm.

Is it too late? Let’s see.

The People vs Tower Hamlets Labour: The Case of Liveable Streets (Low Traffic Neighbourhoods)

“But who’ll defend the workers who cannot organise

There Is Power in a Union – Billy Bragg

When the bosses send their lackeys out to cheat us?”

In retrospect, the Liveable Streets saga, Tower Hamlets Labour’s ambitious endeavour to establish Low Traffic Neighbourhoods, can now be viewed as the proverbial straw that shattered the camel’s back. Finally rupturing the relationship between Tower Hamlets Labour and the working-class communities it purported to represent.

Setting aside the Department for Transport’s assertion that these schemes fail to alleviate traffic congestion, and the unsettling questions surrounding the allocation of approximately £5 million to external consultants by Tower Hamlets Council. One cannot overlook the staggering number of signatures collected in opposition to the project.

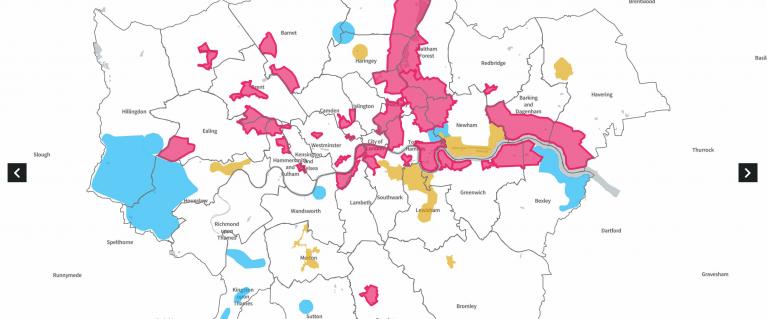

A formidable tally of around 10,000 signatures was amassed through various petitions, predominantly emanating from the safe Labour wards nestled in the northern reaches of the Borough, extending in a broad arc from Shoreditch and Bethnal Green to the Bow area. A cursory sampling exercise I undertook revealed that more than half of these signatories did not hail from migrant backgrounds or identify as BAME. Despite suffering defeat in the Weavers ward by-election, where Aspire championed the cause against Liveable Streets, the Tower Hamlets Labour leadership remained obstinately oblivious.

Had they engaged in rudimentary calculations on the back of a fag packet, they would have swiftly discerned that this campaign, along with its resolute constituents, posed an existential threat to the very foundations of the Tower Hamlets Labour Party. Instead of attending to the legitimate concerns or initiating a constructive dialogue, residents were met with vicious attacks from Tower Hamlets Labour councillors, both on social media platforms and within the chambers of the council. The dismissive treatment of their concerns provoked ire among lifelong Labour Party voters and members, their discontent palpable.

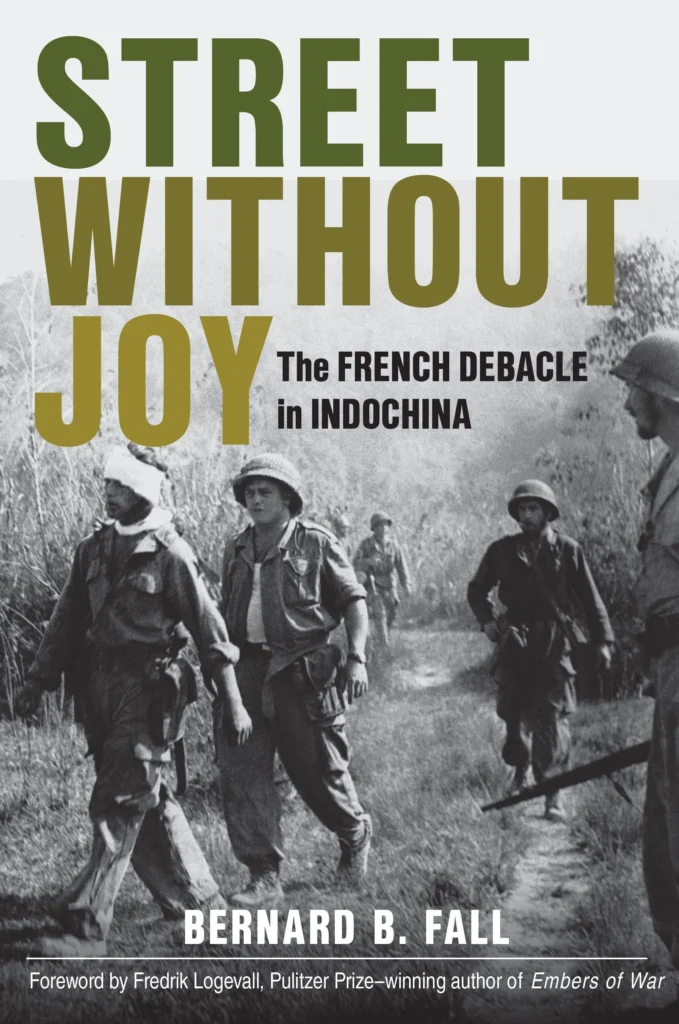

Thus unfolded a battle of wills between the toiling residents of the East End and Tower Hamlets Labour. Looking back, drawing on my own heritage steeped in the political traditions of the global south and its fervent ‘Wars of Liberation,’ it seemed akin to reliving the historic Battle of Dien Bien Phu. An epic battle where Vietnamese rice farmers vanquished a professional French colonial army backed by the United States. My role as the French journalist, Bernard B Fall, observing and writing about the ongoing running battles.

The Town Hall became the epicentre of relentless assaults, a barrage of petitions boasting 5,000 signatures, 2,500 signatures, 1,500 signatures in an open letter directed at Bethnal Green councillors, and another 1,000 signatures in an open letter addressed to Whitechapel councillors. Ultimately, the hitherto underestimated force of what French philosopher Michel Foucault termed ‘biological power,’ in contrast to the entrenched ‘institutional power’ of Tower Hamlets Labour, found solace in Mayor Rahman and his Aspire Party. Their irresistible appeal lay in the straightforward manifesto pledge to restore unrestricted access to the roads.

For me, the most salient aspect of this entire affair lies in the Tower Hamlets Labour leadership’s inability to grasp the profound insights elucidated by Michael Young in his seminal work, “Family and Kinship in East London.” Regrettably, they failed to recognize the enduring vitality of extended familial bonds and the webs of kinship that persist within working-class communities. The prevailing housing crisis has compelled many of these multi-generational families to disperse across the borough. Liveable Streets, in severing these crucial support networks, inadvertently deprived the young, disabled, and elderly of their indispensable lifeline—the automobile.

In anticipation of a probable response defending Tower Hamlets Labour’s alleged affinity with working-class realities—a retort along the lines of, “But I am working class, how can I be detached?”—and its corollaries invoking personal experiences such as having benefitted from free school meals, allow me to preemptively address this logical fallacy before proceeding further.

The Tower Hamlets Labour Logical Fallacy: “I’m from a working-class background, how can I be detached from working-class realities.”

“Money speaks for money

There Is Power in a Union – Billy Bragg

The Devil for his own

Who comes to speak for the skin and the bone?”

Introducing the World of Logical Fallacies

A logical fallacy refers to a mistake or flaw in reasoning that renders an argument invalid or unsound. It deviates from logical principles and proper reasoning, which can weaken the credibility and strength of an argument. Logical fallacies can take different forms, including errors in argument structure, flaws in premises or assumptions, or the use of inappropriate reasoning techniques. A lesson lost on the Tower Hamlets Labour Party.

There are numerous types of logical fallacies, including but not limited to:

- Ad Hominem: Wherein the assailant forsakes the merit of an argument to launch a personal assault upon its proponent. By divesting the discourse of its substance, this fallacy conveniently sidesteps the need to address the argument’s essence.

- Strawman: Erects an artifice of misrepresentation, distorting an opponent’s argument into an easily assailable caricature. This act of intellectual sleight-of-hand facilitates the demotion of an otherwise formidable argument to a feeble construct, ripe for refutation.

- Appeal to Authority: Whereby the effusive opinion or testimonial of a venerable figure assumes the garb of evidentiary weight. However, the authority thus invoked may not possess the requisite expertise in the relevant domain, rendering this fallacy a precarious foundation upon which to construct cogent arguments.

- False Cause: Ensnares the unsuspecting in the quicksand of erroneous causality. This fallacy succumbs to the temptation of inferring a causal relationship between two events solely based on their temporal confluence, devoid of substantive causal evidence.

- Circular Reasoning: Wherein the conclusion of an argument masquerades as a premise. By presumptuously assuming the truth of the very statement under scrutiny, this fallacy perpetuates an endless cycle of self-referential reasoning, bereft of substantive justification.

- Hasty Generalisation: Extrapolates a sweeping conclusion from meagre or unrepresentative evidence. Succumbing to the allure of hastily drawn inferences, this fallacy disregards the prerequisites of comprehensive investigation and statistical rigour.

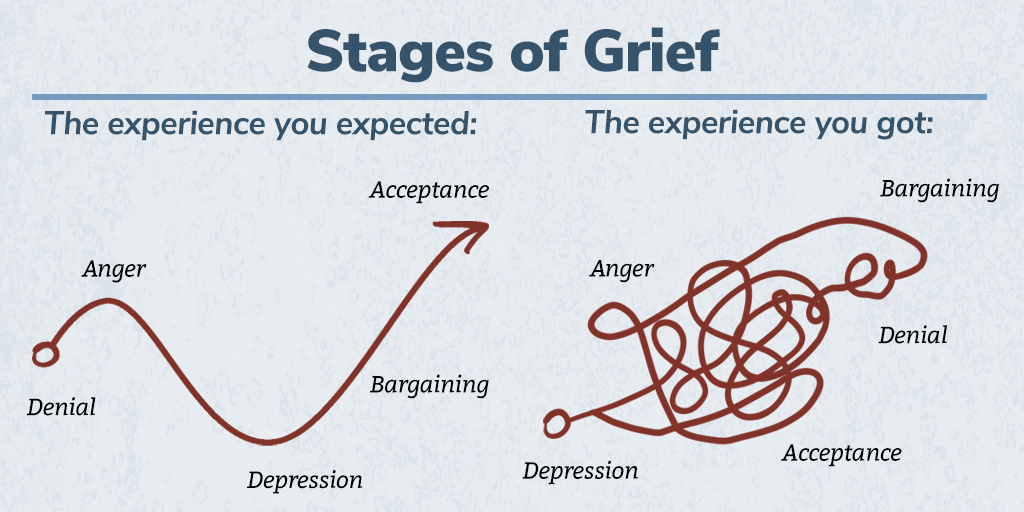

The Tower Hamlets Labour’s logical fallacy of, “I’m from a working-class background, how can I be detached from working-class realities”, is a combination of the above logical fallacies. Instead of looking at the outcome of its action or wholesale rejection by working-class communities in Tower Hamlets, instead the internal discourse within Tower Hamlets Labour resembles a stream of consciousness based on logical fallacies. Still in a stage of denial, instead of accepting and moving on.

Introducing the World of Material Conditioning

Material conditioning, within the context of societal dynamics. It pertains to the notion that the material conditions prevailing in a given society, particularly its economic framework and the apparatus for production, play a decisive role in shaping and determining social relations, world-views, and the conduct of individuals. As posited by this theoretical framework, the mode of production and the relationships engendered thereby constitute foundational elements in comprehending and dissecting the actions undertaken by individuals.

To illustrate this proposition in a rudimentary manner, consider the case of an individual who, by all accounts, possesses no viable prospects within the conventional job market. Nevertheless, by some fortuitous circumstance, this person manages to secure a political position, thereby acquiring an annual income and access to alleged sundry purported “material benefits.” Given such newfound incentives, this individual becomes disinclined to disrupt the status quo, abstaining from scrutinising or challenging the political structures or decision-making processes that sustain their financial remuneration. Therefore, people are incentivised to go against their community interests, for personal financial gains. Another case of the moral hazard of socialised losses and individual gains.

Now we have covered the theory side of Tower Hamlet Labour’s logical fallacy, “I’m from a working-class background, how can I be detached from working-class realities”, let’s have a look at the facts.

Introducing Tower Hamlets Labour’s Material Facts

Examining the macro-level facts, it becomes evident that the material conditions of working-class communities in Tower Hamlets have deteriorated rather than improved during the seven-year tenure of Tower Hamlets Labour under the leadership of John Biggs. Some argue that these conditions are influenced by global forces, such as the war in Ukraine, or the actions of the central government, like the poorly executed budget presented by former Prime Minister Liz Truss.

Yet, upon closer examination, one cannot help but question the veracity of such claims. Tower Hamlets’ working-class households consistently find themselves at the nadir of societal advantages. They languish as the highest proportion of children experiencing food poverty, while during the recent pandemic, grappling with alarmingly elevated rates of COVID-19 fatalities.

“Putting these percentages into numbers, in the months of March, April and May this year over 10,000 more Londoners than usual died. At the height of this fatal wave in April, nearly 200 people a day were dying in London. At least 1,100 of these deaths (or over 10%) occurred amongst Tower Hamlets residents, in a borough which has one of the highest child poverty rates in the country. In the latest statistics on levels of deprivation, published in 2019 by the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, Tower Hamlets remains the local authority with the highest levels of income deprivation in the over-60s. This is a combination of factors that has contributed to the particularly large number of fatalities from Covid-19.”

A Track and Trace plan to more deaths – Puru Miah

An astonishing one in ten London deaths during the pandemic transpired within the confines of Tower Hamlets, even surpassing Oldham, home to England’s second-largest Bangladeshi community. These grim statistics lay bare the exacerbation of the working-class communities’ material decline under the aegis of Tower Hamlets Labour. A disconcerting reality unfolds—a detachment from the plight of these communities, eternally etched in the trenches dug during the pandemic. The sombre burial grounds of East London, as the fallen from Tower Hamlets find their final abode.

The composition of the Tower Hamlets Labour Group from 2018 to 2022 offers further insight into this disconnection from working-class realities. Recent data derived from the 2021 census illuminates Tower Hamlets’ ignominious distinction as the local authority area with the lowest homeownership rate. A mere 25.7 per cent of households in this borough can claim the cherished title of homeowners. Yet, in January 2021, when the Conservatives presented a motion, mirroring the actions of other Labour Councils, aimed at bolstering regulations for landlords, the Tower Hamlets Labour Group diluted the motion. The ensuing debate revealed a disconcerting truth: an alarming over-representation of landlords within the ranks of Tower Hamlets Labour, with more than one in ten proudly holding the mantle of HMO landlords.

Such detachment from the realities experienced by the working class, coupled with a resounding rejection of Tower Hamlets Labour by working-class residents spanning various races and creeds, compels us to ponder a profound question: If the Tower Hamlets Labour Party does not fulfil its role as the vehicle for working-class political representation, then what purpose does it truly serve?

Further Reading:

- A Track and Trace Plan to more deaths by Puru Miah

- Death of Mizanur Rahman & System Failure in Tower Hamlets by Puru Miah

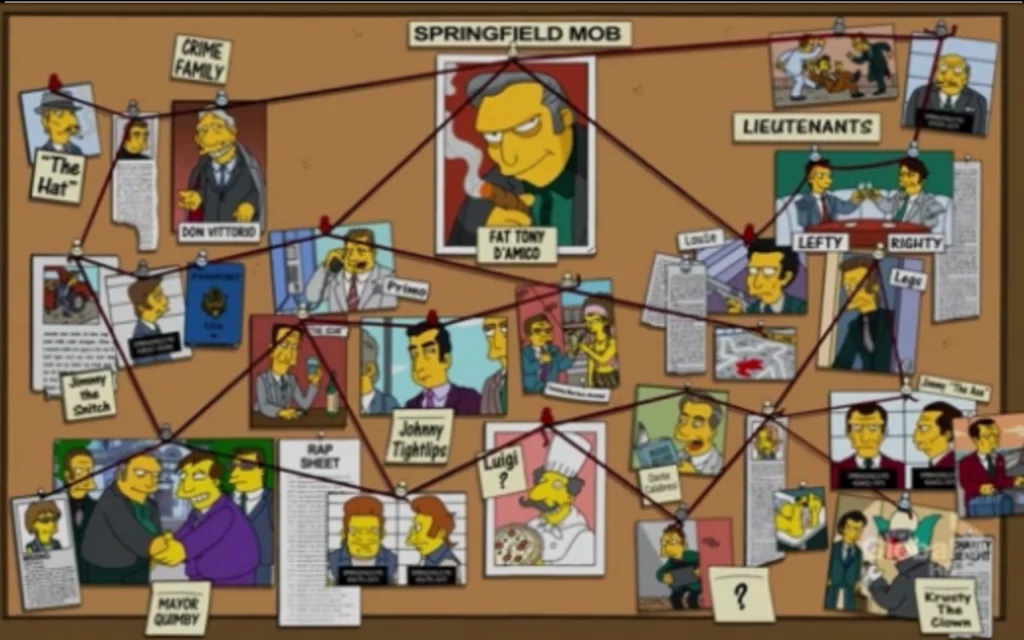

Tower Hamlets Labour: A political party or a rent-seeking vehicle for local cartels?

“The mistakes of the bosses we must pay for

There Is Power in a Union – Billy Bragg

From the cities and the farmlands”

In one of my profound exchanges with the late Mark Banes, an esteemed local investigative journalist, I found myself grappling with the bewildering realm of Tower Hamlets Labour—a political microcosm reminiscent of Alice’s whimsical Wonderland. As the conversation unfolded, I drew upon the illuminating impressions left by a YouTube exposé on the underbelly of corruption within China’s Communist Party.

These reflections served as a lens through which I was able to explain the culture I found in Tower Hamlets Labour, as a councillor. I endeavoured to elucidate the unintended repercussions of residing in a one-party local state—a peculiarly intriguing domain that has earned the infamous moniker of a “rotten borough” in the pages of the satirical magazine ‘Private Eye’.

The quirk of our electoral system, specifically the First Past the Post mechanism, has effectively engendered a hegemony of the local Labour Party—an entity that has metamorphosed into a veritable one-party rule. This stark reality has magnetized individuals to the folds of the Labour Party in Tower Hamlets. Not out of an ardent commitment to champion the aspirations of the working class, but rather as a means to capitalize on the economic benefits that accrue from political rent-seeking. A strategic endeavour to harness fiscal advantages via political avenues. Unlike other local Labour Parties, who are typically bound by the tenets of rigorous selection processes. These are done away with in Tower Hamlets, for example, basic literacy and numeracy requirements, the Tower Hamlets Labour Party finds itself perilously vulnerable to the clutches of those with vested interests in rent-seeking activities.

At its core, political rent-seeking constitutes the comportment of individuals, groups, or organisations endeavouring to secure economic privileges or advantages through the manipulation of political apparatus, rather than by engaging in productive endeavours within the marketplace. Creating inefficiencies and quirks in the marketplace as well as in the distribution of public goods and services.

This Machiavellian pursuit manifests through the astute deployment of political influence, lobbying prowess, and the artful manipulation of local government policies and regulations, all aimed at procuring preferential treatment, subsidies, or other forms of advantageous treatment that confer economic gain.

What is Political Rent-Seeking?

The spectre of rent-seeking assumes multifarious forms, encompassing:

1. Lobbying: At its zenith, rent-seeking materialises through the diligent cultivation of lobbying networks. Wherein individuals or organizations endeavour to sway the minds of decision-makers, deftly manoeuvring to secure the passage of decisions or regulations that favour their parochial interests. Notably, such endeavours often encompass generous financial contributions to political campaigns, the enlistment of influential lobbyists, and the exertion of calculated pressures on the corridors of power—particularly those associated with planning and licensing committees.

2. Capture of Regulatory Agencies: Astute rent-seekers endeavour to assert control or influence over regulatory agencies tasked with adjudicating decisions or enforcing rules that bear upon their particular industry. By subverting the institutional apparatus, they deftly mould regulations to their advantage, erecting barriers to competition and assiduously shaping a landscape that is in consonance with their own interests. The tentacles of such machinations often extend into the intricate web of planning and licensing committees.

3. Subsidies: A hallmark of rent-seeking resides in the relentless quest for subsidies, grants, or tax breaks from local governments—an artful manoeuvre designed to obviate costs, inflate profits, and erect impenetrable barriers for prospective competitors. Such incentives are aptly calibrated, and aimed precisely at specific industries, companies, or even individuals, invariably engendering distortions within the market fabric. One illustrative example is the deliberate curation of allocations and rent reductions on properties owned by the local council.

4. Corruption: The murky realm of rent-seeking is not immune to the insidious tendrils of corruption. Instances abound wherein rent-seekers engage in illicit practices such as bribery or kickbacks, their sole objective being to secure favourable treatment or illicit access to valuable resources from the coffers of local government. This ignoble conduct serves to corrode public trust, erode institutional integrity, and debilitate the process of economic development—an affliction that afflicts even the most sacrosanct pillars of governance.

The pernicious ramifications of political rent-seeking ripple throughout the economy and society at large. They conspire to engender the inefficient allocation of resources, stifle competition, and impose exorbitant price burdens upon the shoulders of residents. Moreover, rent-seeking fosters an insidious culture of political corruption exacerbates existing inequalities, and corrodes the bedrock of public trust, engendering a palpable sense of injustice and disillusionment with the political edifice.

Whether the Tower Hamlets Labour Party truly epitomises a political institution or has metamorphosed into an entrenched vehicle for rent-seeking remains a question that will be conclusively answered in the fourth and final instalment of this series. A profound exploration that shall excavate the depths of Tower Hamlets Labour and its constituent elements. But before we draw the final curtain, let us harken back to the wisdom imparted by Michael Young, the author of “Family and Kinship in East London.”

“Reject the values and false morality that underlie these attitudes. A rat race is for rats. We’re not rats. We’re human beings.

Reject the insidious pressures in society that would blunt your critical faculties to all that is happening around you, that would caution silence in the face of injustice lest you jeopardise your chances of promotion and self-advancement.

This is how it starts and before you know where you are, you’re a fully paid-up member of the rat-pack. The price is too high. It entails the loss of your dignity and human spirit.

Or as Christ put it, “What doth it profit a man if he gain the whole world and suffer the loss of his soul?”

Jimmy Reid – Trade Union Leader (1932 – 2010)

A Tribute to Michael Young: 70 Years On, Reflections from “Family and Kinship in East London”.

“The Union forever defending our rights

There Is Power in a Union – Billy Bragg

Down with the blackleg, all workers unite”

Michael Young’s exploration of housing and local government policy in East London, stemming from his doctoral thesis, left him disenchanted with the state of community relations and the efficacy of local Labour councillors. This dissatisfaction prompted him to establish the Institute of Community Studies as a primary platform for his pursuit of social reform. At the heart of Young’s philosophy lay a fundamental tenet: empowering individuals to have a greater voice in shaping their lives and the institutions that govern them.

In her thought-provoking paper titled “Michael Young, the Institute of Community Studies, and the Politics of Kinship.” Dr Lise Butler argues that Young drew upon existing research in social psychology and sociology to underscore the enduring relevance of the extended family in modern society. Departing from the conventional focus on productive work, Young proposed a model of socialist citizenship founded on solidarity and mutual support. He championed the resilient kinship networks present within the urban working class and idealized the dynamics between women, positing that the left had overlooked the transformative power of family, which should be reclaimed as a progressive force. The ultimate aim was to fortify the working-class family and present it as a blueprint for cooperative socialism.

Consequently, Young concluded that the Tower Hamlets Labour Party may not be the sole vessel for the aspirations of the urban working class. Instead, he proposed the establishment of diverse civic institutions that can provide support and uplift the material conditions of these individuals. By expanding the scope of participation beyond traditional party politics, Young envisioned a more comprehensive framework to address the needs and aspirations of the working class in a rapidly evolving urban landscape. 70 years on, perhaps he is right.

”With our brothers and our sisters

There Is Power in a Union – Billy Bragg

Together we will stand

There is power in a Union”

Recent Comments