A Personal Journey of Exploration of the “Bengal Renaissance”, and Beyond the Established Binaries, are often expressed when it comes to South Asian History and Heritage. With suggested reading material at the end.

Introducing South Asian Heritage Month (SAHM)

South Asian Heritage Month (SAHM) aims to honour and celebrate the diverse cultures, histories, and communities of South Asia, forging a meaningful connection with the United Kingdom.

South Asian influence is evident throughout Britain, leaving a significant impact on various aspects of life, including food, clothing, music, language, and the overall ambience of our towns and cities. The fusion of South Asian heritage into British life showcases a beautiful amalgamation that adds to the rich diversity of our nation. Embracing South Asian Heritage Month provides a valuable opportunity to appreciate and celebrate the history and identity of British South Asians.

It is essential to create a platform for individuals to share their personal stories, allowing them to showcase what it means to be South Asian in the 21st century, while also reflecting on the past and its impact on shaping the present.

The month’s chosen period is from the 18th of July to the 17th of August. It holds historical significance as it marks the Indian Independence Act of 1947 and the publication of the Radcliffe Line, which defined the borders between India, West Pakistan, and East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). This timeframe aligns with the South Asian month of Saravan/Sawan, a period of renewal during the monsoon season, respecting the traditions of South Asian calendars. It also encompasses various independence days of South Asian countries.

However, can the stories of South Asian heritage be told beyond the confines of the Radcliffe Line and Partition, moving beyond religious binaries of Muslims and Hindus, and transcending distinctions between migrants and non-migrants in the UK?

Perhaps by broadening the narrative, we can appreciate the interconnectedness and shared experiences that go beyond artificial divisions, promoting unity and understanding among all communities.

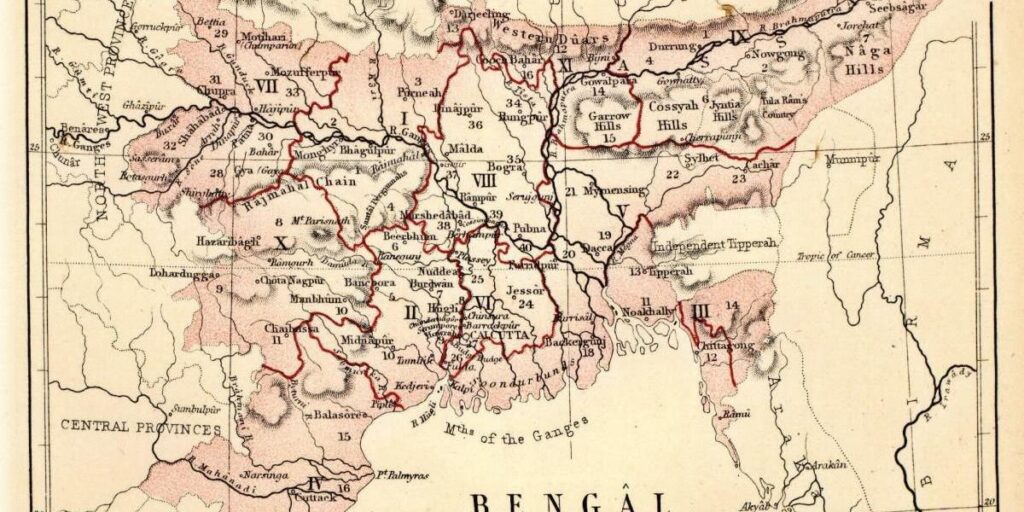

Introducing the Bengal Renaissance

Modernity arrived in Bengal through global trade. However, with the military takeover by the East India Company in 1757, a complex interplay of colonial dominance and anti-imperial resistance, remoulded this modernity into a new cultural expression, a renaissance. The Bengal Renaissance was a cultural and intellectual movement that swept across the Bengal region of the Indian subcontinent in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Defined by a rekindled interest in the region’s history, language, literature, and art, the Renaissance was driven by a dynamic and educated middle class.

The Bengal Renaissance can be seen as an attempt to transcend the binaries, often imposed on South Asia by the British Raj, through legal reforms dividing communities into fixed castes, tribes, and religions. Which Professor Mahmood Mamdani explores in his work ‘Define and Rule: Native as Political Identity’.

At the heart of the Bengal Renaissance were towering figures such as Raja Ram Mohan Roy, Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, and Rabindranath Tagore. Roy, a polymath and social reformer, agitated for a wide range of progressive causes, including women’s rights and the abolition of the caste system. Vidyasagar, a tireless advocate for education and social reform, campaigned for the education of women and the elimination of child marriage. Tagore, a prodigious polymath and artistic visionary, was a prolific writer, poet, and painter. In 1913, he became the first non-European to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.

The Bengal Renaissance was also marked by a flourishing of Bengali literature, which focused on contemporary social issues and emphasized the use of vernacular language. This literary flowering was closely linked to the broader social and intellectual ferment of the period.

The link with the United Kingdom and its influence had much bearing on the Bengal Renaissance and vice versa. So what are these links?

Introducing the 400-year-old relationship between the East End and Bengal

Tower Hamlets boasts one of the most enduring South Asian communities in Western Europe, predominantly comprised of Bengali/Bangladeshi individuals. The Bengali presence in the East End of London has a remarkable history, dating back nearly 400 years to the time of the East India Company’s commercial ventures. The company’s headquarters were conveniently located near Aldgate, and the East End served as the hub for its docks and warehouses.

As trade flourished, so did the arrival of travellers from Bengal. Among the earliest recorded visitors was I’tisam-ud-Din, a Bengali Muslim, who set foot in Britain in 1766 and later documented his experiences in 1785 through his work “Shigurf Namah i Vilayat” (“The Wonders of Europe”). This marked the beginning of a trend that continues even today, with the East End and its vibrant markets remaining the primary destination for travellers originating from Bengal, now known as modern-day Bangladesh. Over the passing centuries, each generation has contributed to the tapestry of the East End’s cultural richness, ensuring a lasting legacy of diversity and heritage.

So what of this experience now in 2023?

Introducing a Canon of Literature? To aid in exploration beyond binaries of the relationship between the East End and Bengal.

At the suggestion of a friend, will be exploring the experience through the literature of the Bengal Renaissance, starting with the theme of politics. Not just the literary texts but their meanings, in today’s East End. With the target of finishing each work each month, writing a piece on the experience along with an explainer video.

The issues addressed in these texts—and in political theory generally—fall into three broad categories.

The first involves the essential characteristics of human nature and the good society:

- Is human nature essentially spirit or matter?

- Is it directed by reason or dominated by passion?

- Is it fixed or malleable?

- Is it innately sinful, aggressive, and violent, or is it fundamentally benign, cooperative, and non-violent?

- Will a good society be characterized by perfect harmony or by continued conflict?

- If conflict is inevitable in a good society, must it be controlled through the leader’s discretionary use of coercive power, or can it be contained constructively within political institutions?

- Are social unity and harmony achievable or even desirable?

- Do the progress and vigour of society depend, by contrast, upon some form of struggle?

The second set of fundamental questions involves the relationship between the individual and society:

- What is the right relationship of the individual to society?

- What is the relationship of individual freedom to social and political authority?

- What constitutes legitimate political authority?

- Does it come ultimately from God, the state, or the individual?

- Are human beings fundamentally equal or unequal?

The final set of questions involves theories of change:

- What are the fundamental dynamics of change?

- What role is played by discretionary leadership or moral values in effecting change?

- Are there inexorable laws of history that produce change?

- Is an unchanging, enduring, universal system of ethical values possible?

- Must such a system be grounded in a theory of absolute truth?

- If an enduring, universal system of values is possible, what precisely are those values, and what is their relevance for political and social action?

- Should transformative leadership be based on the hard facts of political reality and human weakness, or on the knowledge of absolute truth?

- Is the most fundamental change ideological, economic, or psychological in nature?

- Should agents of change pursue reform through gradual, evolutionary means, or should they follow the total transformation of society and human nature through revolution?

- Should radical change be pursued through violence or non-violence?

- Should it rely mainly on spontaneity or on authoritarian organization?

The books are:

1. Anandamath – Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay

2. Nil Darpan – Dinabandhu Mitra

3. Gora – Rabindranath Thakur

4. Hanshuli Banker Upakatha – Tarashankar Bandopadhyay

5. Deshe Bideshe – Syed Mujtaba Ali

6. Padma Nadir Majhi – Manik Bandopadhyay

7. Pather Panchali – Bibhuti Bhusahn Bandopadhyay

8. Pratham Pratishruti – Ashapurna Debi

9. Hajar Churashir Maa – Mahashweta Debi

10. Na Hanyate – Maitreyi Debi

Want to take part? The more, the merrier, email me: [email protected]

NOTE: I have been informed, that English translations are available of all the above works, with extensive commentaries. So anyone can take part, Bangla and English readers. I’m starting with ‘Gora’ by Rabindranath Tagore.

Recent Comments