Extract of paper by Sarah Glynn was published in New Geographies of Race and Racism, Edited by Claire Dwyer and Caroline Bressey, Aldershot: Ashgate pp 67 – 82 (2008)

Introduction

The story of the East End Bengalis and the Labour Party is one of a liaison that has turned sour. And like in many more personal relationships, the forces that finally drove the parties apart are the same that first brought them together. Now, as in

the past, the main force behind East End Bengali politics is a community based pragmatism, and the emergence and subsequent evolution of this can be understood by looking at it in the context of wider developments in progressive politics.

Beginnings: Looking Back to East Bengal

For the earliest immigrants, however, the focus of political activity, as of their lives more generally, was their East Bengali homeland, compounded in the period following the Second World War with immediate concerns over immigration. Many

of these immigrants had little education, and a prominent role was played by a small intellectual elite of students and young professionals who had learnt their politics in the persecuted left and nationalist movements of their homeland. It might have been expected that this would have encouraged the spread of socialist ideas in the immigrant community more generally, but the political approach taken was in line with the popular front politics propagated by the Communist Party, which specified that political ideology be kept in the background.

Popular front principles were applied whether doing grassroots community work or campaigning on major issues such as Bangladeshi independence. Tasadduk Ahmed, who played a pivotal role in British Bengali politics and put the Pakistani

Welfare Association onto a firm footing explained:

“My main experience in the UK has been the experience of how to manage or organize united front activities, keeping my

own belief to myself and to my close associates.”

Fighting for the Bengali Community in London

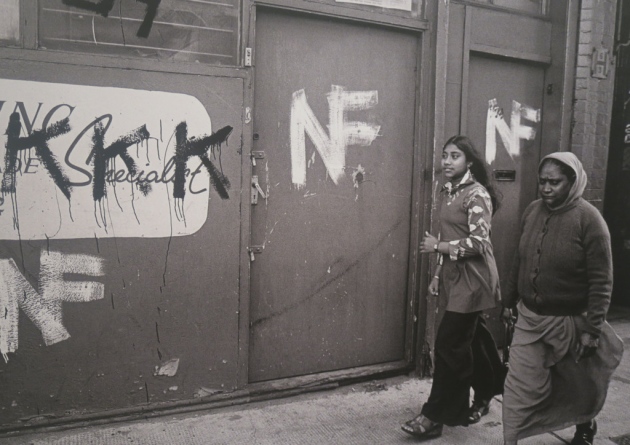

In the late 70s and early 80s East End Bengalis became caught up in two major battles – against an aggressive racism being promulgated by the National Front, and for decent and safe housing. The housing crisis was exacerbated by the arrival of the families, and the new young generation played a major role in the campaigns. Many of them had witnessed radical political action first hand during the war, and unlike the older generation, they saw themselves as permanent immigrants. They were ready to fight for their rights, and it was these battles that mobilized the generation that now makes up the greatest part of the Bengali political establishment.

At the centre of the fight were organizations set up by New Left activists from the Race Today Collective with the ultimate aim of creating a movement for radical black self organization. They were by no means the only organizations working in

the East End, but through their hard fought grassroots campaigns they were able to involve more people and generate more radical forms of protest.

A Community within Mainstream Politics

For most of those involved, community-based activism merged easily into community-based pragmatism. Bengalis were suffering through racism and often appalling living conditions, and they felt the need to help their fellow immigrants the

most efficient way possible. For many this meant joining the Labour Party; and, despite their move to mainstream politics, they generally continued to see themselves as representatives of the Bengali community.

The overriding reason given by my interviewees for joining the party was to continue campaigning for better and fairer treatment of the Bengali community (though of course there were always also those who thought they could achieve this

better outside organized politics). Self-organization, along ‘ethnic’ lines, had mobilized a new layer of activists, but now they wanted access to the mechanisms of power.

In general, Bengali Labour politics can be described as pragmatic, even when it is dressed in socialist rhetoric. However, the object of that pragmatism varies from the ‘community’ to the individual – perhaps portrayed as the true representative of the community.

A Revolution in the Labour Party

At first, though, many of this newly politicised generation found the Labour Party far from welcoming. Some early Bengali immigrants appear to have had no problems in joining their ward parties but many Bengalis were faced with a blank refusal.

Bengali Representation

Within the general give and take of political bargaining, Bengali party members could act as a group quite independently of more orthodox left/right divisions, leading to strange changing alliances.41 Links to different Bengali political parties also play a crucial part in individual political careers and add another layer of bonds and influences.

Other Political Platforms

While there will always be accusations of ethnic voting to ensure Bengali councillors and of white voters not voting for Bengalis, the real electoral battles have been between the politics of the different parties, and the real fight for Bengali

representation has been within the parties. At a local level that has long been won. The 1997 general election saw Bengalis standing across the political spectrum from the Referendum Party to Socialist Labour, and Bengalis currently occupy a disproportionate 31 out of 51 council seats

The Image becomes Tarnished

A generation on, as the young Bengali activists of the late 70s and 80s settled in to become the new political establishment, many Bengali councillors were being criticised in much the same way as they themselves used to criticise the older council regime and their more cautious seniors in the Bangladesh Welfare Association.

Diversity through Gender

Although the British born generation are getting more actively involved, there have been relatively few Bengali women in politics. A combination of language problems, fear of racial attack, and a ‘modesty’ inspired and sometimes enforced by both religion and tradition, still prevents many women from merely going out of their homes; and even when they are backed by a supportive family, women with political ambitions may have problems.

The Era of New Labour

The participation of Bengalis – men and women – was welcomed by Labour as evidence of the party’s antiracist credentials, but multiculturalism can also be used to give a progressive veneer to an administration that has abandoned classbased policies. In addition, the prioritising of cultural identity cuts across class divisions, making this a useful tool for those wanting to turn their back on old labour values.

The Political Lure of Islam, and a New Popular Front

British Muslims were encouraged to express their opposition to the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq under the banner of the Muslim Association of Britain. The MAB played a distinct role in the Socialist Workers’ Party (SWP) dominated Stop the

War Coalition, which was set up to coordinate antiwar protest. In January 2004 this anti-war coalition was formally inaugurated into a new political organization under the banner of Respect, with exLabour MP George Galloway as its most prominent leading figure.

Old Traditions Adapting in New Political Climates

The SWP and Galloway have tried to portray Respect as part of the great East End socialist tradition and left-wing organizations have frequently attempted to generate among the Bengalis an echo of the prewar left movements in which Jewish immigrants played a key part – but class-based politics have never really taken root in the Bengali East End. Even in the early years of the immigration, when most of the political leadership professed allegiance to various Marxist groups, there was no developed sense of class consciousness. Many, such as Tasadduk, were themselves in business; popular front politics incorporated restaurant and workshop owners into leftled agitations; and leftist memories of that time can slip into using the term ‘working class’ to include small businessmen. Trade unionism was never a priority.

Link to full paper: https://sarahglynnblog.files.wordpress.com/2017/10/east-end-bengalis-and-the-labour-party.pdf

Recent Comments