The announcement of a £3.5 million per year funding boost for local voluntary and community sector (VCS) organizations by Tower Hamlets Council has generated significant interest, sparking conversations and debates amongst the community.

In order to fully comprehend the implications of Tower Hamlets Council’s recent funding boost for the Mayor’s Community Grants Programme, it is essential to delve into the context surrounding this development. Additionally, it is crucial to take note of the concerns raised by numerous individuals in the community regarding the potential outcomes of this funding allocation.

A long-form piece full of details covering the following:

- Definition of Technical Terms

- Brief summary of announcement and concerns

- A brief history of Community Grants and Tower Hamlets Council

- Present-day needs and concerns

Definitions

Equalities Act 2010: Is an Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom. With the primary purpose of consolidating, updating and supplementing the numerous prior Acts and Regulations, that formed the basis of anti-discrimination law in mostly England, Scotland, and Wales; some sections also apply to Northern Ireland.

These consisted, primarily, of the Equal Pay Act 1970, the Sex Discrimination Act 1975, the Race Relations Act 1976, the Disability Discrimination Act 1995 and three major statutory instruments protecting discrimination in employment on grounds of religion or belief, sexual orientation and age.

Public Sector Equalities Duty (PSED): The Cabinet Office’s Information Note 1/13, “Public Procurement and the Public Sector Equality Duty”, noted that public authorities needed to have due regard to its duty when planning and undertaking procurement activities. Stating in particular that when contracting out public functions, it would be usual to include contract conditions which specified how equality obligations and objectives were to be complied with.

Due Regard: The duty set out in section 149 requires those public authorities which are subject to it to have due regard to three aims:

- To eliminate unlawful discrimination, harassment, victimisation and any other conduct prohibited under the Act,

- To advance equality of opportunity between people who share a protected characteristic and those who do not, and

- To foster good relations between those who share a protected characteristic and those who do not

Equality Impact Assessment (EqIA): This is a process designed to ensure that a policy, project, or scheme does not unlawfully discriminate against any protected characteristic. The EqIA process aims to prevent discrimination against people who are members of a protected category. The Equality Act 2010 defines 9 protected characteristics:

- Race

- Religion or Belief

- Disability

- Sex

- Gender Reassignment

- Sexual Orientation

- Age

- Marriage or Civil Partnership

- Pregnancy and Maternity

Pork Barrell: The term pork barrel politics usually refers to spending intended to benefit constituents of a politician in return for their political support, either in the form of campaign contributions or votes.

An announcement at the Town Hall and Flashbacks

On April 25th, 2023, Tower Hamlets Council made an exciting announcement: the opening of applications for the Mayor’s Community Grants Programme, along with a £3.5 million per year funding boost for local voluntary and community sector (VCS) organizations. Naturally, this generated a lot of buzz on social media, and I received calls from stakeholders and residents eager to understand the implications of this funding allocation.

One particular call stood out: a journalist reached out to me after being briefed by ‘interested parties’ and doing thorough research. His main concern was whether the Council’s actions would repeat the 2015 testimony made by Deborah Cohen in the Electoral Court.

I did my best to explain the context around the Community Grants Programme and address the journalist’s concerns. I acknowledged the validity of the worries. But I have emphasized that it was too early to tell. Whether the funding boost was merely a fulfilment of the Council’s statutory duty to uphold the Public Sector Equalities Duty (PSED) or whether it signalled a continuation of a political tradition of pork-barrelling.

In order to fully comprehend the implications of Tower Hamlets Council’s recent funding boost for the Mayor’s Community Grants Programme, it is essential to delve into the context surrounding this development. Additionally, it is crucial to take note of the concerns raised by numerous individuals in the community regarding the potential outcomes of this funding allocation.

Below is an explanation of the context as well as the concerns raised by many. First, let us look at the national picture.

History and anatomy of grants to the voluntary sector in Tower Hamlets

Tower Hamlets’ grants to the voluntary and community sector (VCS) in the borough have been a subject of much scrutiny and debate over the past decade. A concise chronicle of this grant’s history encompasses the period commencing prior to Mayor Lufur Rahman’s ascension to office in 2010 and culminates with his recent re-election in 2022, including the Labour administration of John Biggs.

Below is a brief outline of the controversies as well as context.

A. Unclaimed: The impact of poverty on marginalised demographics in accessing public services

A recent report from the charitable organization Trust for London reveals that a staggering 39% of households in Tower Hamlets are living below the poverty line. Poverty is aggravated by the complexity of the benefits system, coupled with a lack of public awareness of available support and the stigma surrounding welfare recipients. Factors that have all contributed to a significant portion of eligible households failing to claim the financial assistance they are entitled to, as outlined in a recent analysis. This unfortunate reality has only exacerbated the poverty crisis in the area, leaving many families struggling to make ends meet.

Policy in Practice has published a recent study revealing that lower-income households in the UK are neglecting to claim benefits and other cash support to which they are entitled. Shockingly, some families could be losing out on up to £4,000 per annum. Nationally, this failure to claim means that UK households are missing out on an enormous £19bn worth of unclaimed welfare benefits each year. The report highlights the systemic issues surrounding the benefits system, which result in a significant proportion of the most vulnerable in society being unable to access vital financial support.

The conundrum of poverty and unclaimed welfare benefits has seen policymakers in local authorities, including Tower Hamlets turn to the Voluntary Community Sector (VCS) as a remedy, investing heavily in such organizations as a means of mitigating financial insecurity. The VCS is seen as a valuable resource in offering social and physical assistance to those seeking financial aid, particularly those trapped in the vicious cycle of poverty.

The underlying rationale is not merely social in nature, but economic as well. The funds disbursed through these programs are considered investments that will eventually produce long-term benefits, including increased income and tax revenues. In this way, the VCS has become a critical element in the struggle against poverty, as well as a crucial tool in the development of sound economic policies that address the challenges of contemporary society.

However, different local authorities have different approaches.

A. Before Lutfur Rahman: Small is Beautiful!

In the realm of poverty reduction, local authorities have two options at their disposal. The commissioning approach entails entrusting a handful of providers with contracts distributed by the council. Alternatively, the micro approach involves a grant system that supports a plethora of smaller groups who possess localized knowledge and intersectional expertise, providing assistance to disadvantaged demographics who have been left behind. Moreover, such an approach not only assists these groups but also advocates on their behalf.

In Tower Hamlets, by a stroke of luck rather than intention, the local council has historically embraced the latter micro approach. This approach aligns with the “Small is Beautiful” philosophy espoused by the esteemed economist Ernst Friedrich “Fritz” Schumacher. Modern-day proponents of this philosophy also prioritize people-centric technical solutions. The current manifestation of this philosophy, known as the Appropriate Technology Movement, involves selecting and implementing small-scale, cost-effective, decentralized, labour-intensive, energy-efficient, environmentally sustainable, and locally autonomous technologies.

When I was chosen as the Labour candidate in Mile End in 2017, preserving this approach was of the utmost importance to me. However, before we delve into that, it is necessary to examine the controversy surrounding grants to the VCS (Voluntary and Community Sector) in Tower Hamlets, prior to the Labour Party’s ascension to power in 2015.

B. Lutfur Rahman, 2010 – 2015: Panorama, Eric Pickles, and the Electoral Court.

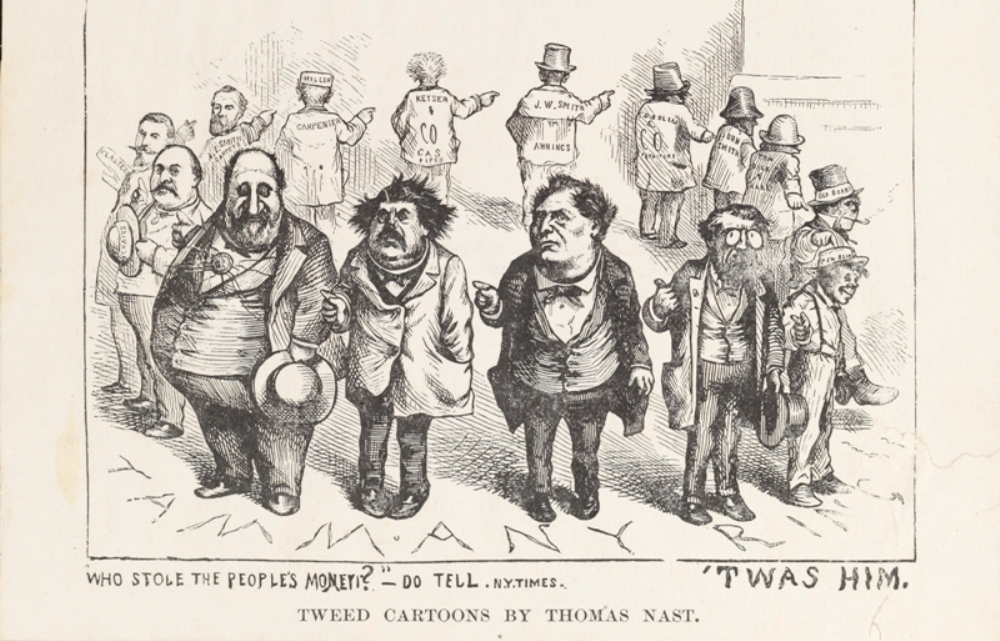

In the lead-up to the 2014 council elections in Tower Hamlets, a Panorama programme aired by the BBC raised serious questions about the fitness of Lutfur Rahman, mayor of the borough, for office. The show alleged that Rahman had used his position to double funding for Bengali/Somali-run charities over the recommendations of council officers, and that he had selected grant recipients with an eye toward electoral gain.

Panorama alleged, that Mayor Rahman increased funding for these organizations by nearly two-and-a-half times, to a total of £3.6m, using council reserves to cover the cost and reducing the amount available for other organizations by 25%. Opponents claimed that Rahman had made the grants in exchange for electoral support.

Following the allegations, The Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy’s CEO, Rob Whiteman, called for transparency in decision-making to avoid questions about the integrity of the process. Following the allegations, Eric Pickles, the then Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government, dispatched Commissioners to run the council.

The 2015 Electoral Court judgement against Lutfur Rahman, relied heavily on the testimony of a former council officer regarding allegations of corrupt practices. Deborah Cohen’s testimony in the eyes of the judge made Mayor Rahman a bad character, allowing the judge to discount any testimony forwarded by Mayor Rahman during the trial.

Rahman’s removal from office prompted a by-election, which was ultimately won by the Labour Party. The new leadership of the council, under Mayor John Biggs, sought to distance itself from Rahman’s administration and implement reforms aimed at restoring public trust in the borough’s governance.

C. Labour Administration, 2015 – 2022: Municipal Neo-liberalism under Mayor John Biggs?

Small is still Beautiful!

After the Panorama revelations in 2014 and the subsequent election of Mayor Rahman. The Secretary of State, Eric Pickles, sent commissioners to Tower Hamlets Council to take control of some of its functions, including grant-making, contract procurement, and selling off valuable council real estate.

When Labour regained power in 2015, the commissioners were still there, and they focused particularly on the grants given by the Council to the Voluntary and Community Sector (VCS) in Tower Hamlets. In 2016, Sajid Javid, the then-Secretary of State, announced that grant-giving powers would be given back to Tower Hamlets Council. By March 2017, full powers were granted to the council.

It was in November 2017 that I was selected as the Labour councillor candidate for Mile End. Shortly after being selected, I learned through informal channels that the Labour administration was considering transitioning to a commissioning system for large contracts to a select few organizations, in an attempt to distance themselves from previous controversies.

With the help of VCS stakeholders, I successfully lobbied for a delay of any such move until after the elections. This gave me the opportunity to add lines to the Labour manifesto for a continuation of the previous approach, which included grant funding for a strong network.

“We will continue to support, through grant funding and commissioning, and partnership with others, a strong network of support, advice, training and community capacity building projects, centres and initiatives. These both help people in poverty, reducing social exclusion, while also providing ladders and opportunities.”

Page 32, Tower Hamlets Labour Manifesto, 2018

Grant Funding or Commissioning?

In May 2018, I was elected as the Labour Councillor for Mile End. Labour had garnered a renewed mandate to govern the council for another four years.

However, controversy swirled around the administration in the wake of our initial budget, reigniting debates surrounding Council Grants to the Voluntary and Community Sector (VCS). In this charged environment, I and a coterie of like-minded councillors valiantly advocated for the preservation of the extant grant allocation scheme, rather than a move towards commissioning. Our impassioned pleas reminded the administration of the salient commitments made in the manifesto.

But our argument was not solely predicated on technical grounds. Rather, we persuasively argued that there would be profound political ramifications arising from any substantive modifications to the existing grant framework. Such alterations would inevitably create winners and losers. In light of this, we stood resolute in our stance against commissioning.

Reassured that there would be no encroachment upon the status quo, we departed the Town Hall, our minds at ease. Yet unbeknownst to us, the Mayor had clandestinely decided to straddle the fence by pursuing a hybrid model of commissioning and grant funding. Fully cognizant of the attendant political fallout, the Mayor appointed an ‘independent assessor’, ostensibly to maintain a veneer of impartiality. Thus did the administration engage in a cynical game of political expediency, pitting winners against losers while attempting to evade accountability for the aftermath. This turn of events had both winners and losers, as well as significant political fallout.

From Pork Barrell to Apartheid?: Political Fallout and heated debates in the Town Hall and High Court

With many political decisions, the allocation of funds to various organizations can have unforeseen consequences. This was certainly the case in a London Borough where a majority of residents identify as being from an ethnic minority. Surprisingly, despite this demographic makeup, most of the organisations that were defunded were BAME-led, with no Somali-led organization receiving any funding.

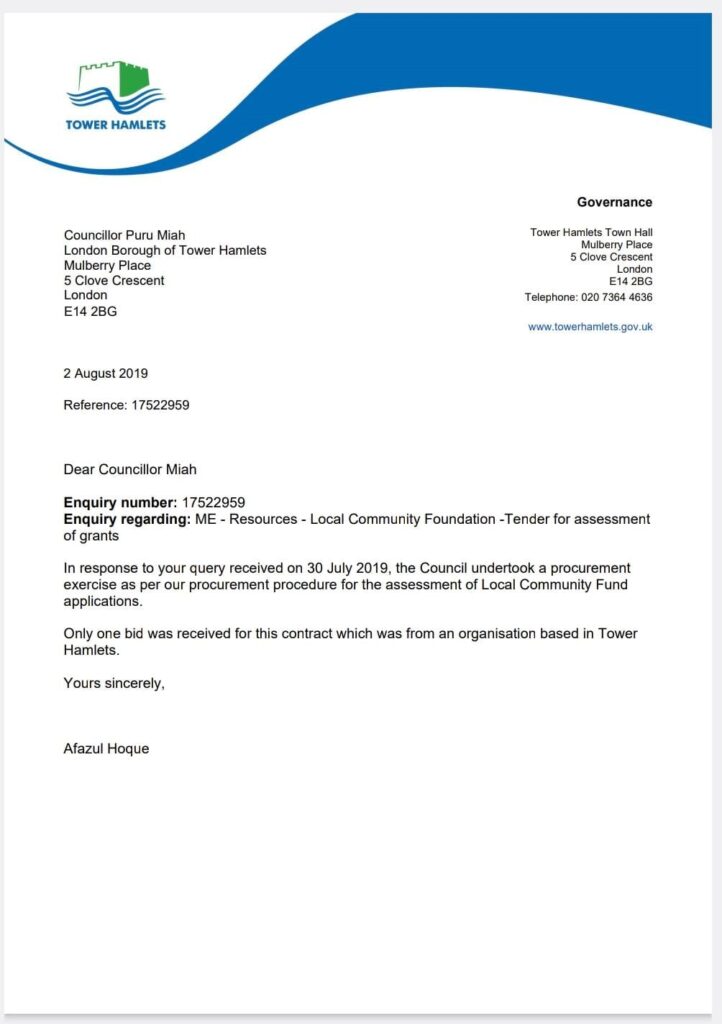

The reasons for this outcome can be traced back to two main factors. The first was the appointment of an ‘independent assessor’ to evaluate grant applications. The assessor, however, lacked any background in dealing with BAME communities, and its leadership and management were non-BAME. Furthermore, only one bid was received for the contract to be the independent assessor of these grants, leaving much to be desired in terms of a competitive bidding process. As a result, small BAME-led organizations with low financial turnovers found themselves unable to compete with larger organizations like the Citizen Advice Bureau of Hackney. Although the assessor treated all applications equally, it did not treat them equitably, leading to an unfair distribution of funds.

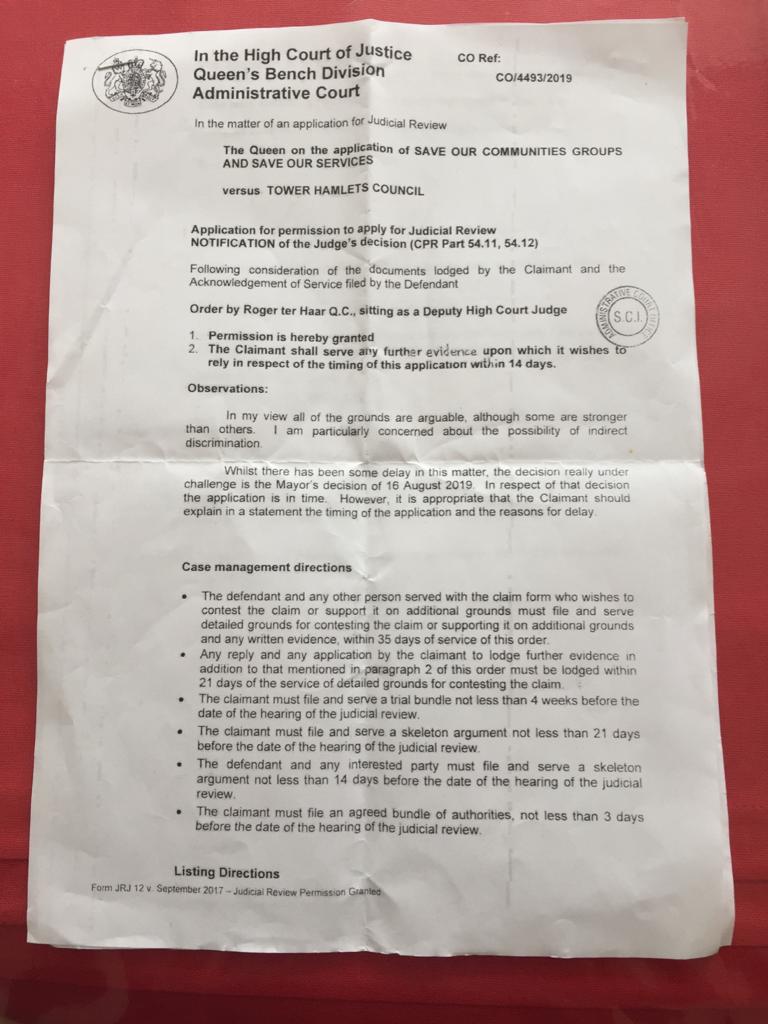

The second factor was the Labour Administration’s failure to address this injustice. Despite a successful call-in to halt the process and review the assessor’s allocations, Mayor Biggs and his administration chose to ignore the issue and pretended that everything was well. This “bury your head in the sand” approach was in stark contrast to the acceptance of an application in the High Court, where a judge found that there was a prima facie case of discrimination. This lack of political responsibility and inaction on the part of the Labour Administration only served to compound the problem.

The result of this flawed decision-making process was a complete reversal of fortunes. Initially, Mayor Rahman was accused of practising pork-barrel politics by awarding grants to BAME lead organizations, the Labour administration was now being accused of practising an apartheid-like process in refusing their applications. This shift in narrative fed into the existing perception of a Labour administration incapable of dealing with multi-racial issues and ultimately led to a crushing defeat in the 2022 elections.

In the end, it was a painful lesson in the importance of understanding the complexities of racial and ethnic diversity and the need for equitable decision-making processes. The consequences of this flawed decision-making process were far-reaching and demonstrated the significant impact that political decisions can have on marginalized communities.

Present-Day Needs vs Present-Day Concerns

Mayor Lutfur Rahman’s recent announcement regarding additional funding for the voluntary and community sector (VCS) in Tower Hamlets has been met with mixed reactions. While it is undoubtedly a step in the right direction, certain caveats must be considered before full-fledged support can be extended. As I elucidated earlier, the benefits of investing in the VCS far outweigh the short-term costs, and any funding directed towards redressing the shortfall faced by groups with protected characteristics, as defined by the Equality Act, is a welcome move.

However, according to the Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy (CIPFA), the process of allocating funds should be conducted in an open and transparent manner. The latest census data ought to serve as an empirical guideline and must be applied to the statutory framework laid out in the Equality Act. Failure to adhere to these standards will inevitably result in allegations and controversy surrounding the grant allocation process led by Mayor Lutfur Rahman. In such an eventuality, it is the most vulnerable members of Tower Hamlet’s society who will be the hardest hit.

The imperative to eradicate political interference from grant-making decisions has become a pressing concern in Tower Hamlets. The allocation of grants ought to be grounded in incontrovertible facts and the demonstrable needs of the communities in question. The spectre of pork barrel politics looms large, particularly in the aftermath of the first Mayor Rahman administration, which was dogged by allegations of such malfeasance. Meanwhile, the previous Labour administration was not immune to allegations of racial discrimination, casting a pall over the grant-making process.

The remedy for such malfeasance is readily apparent: transparency and a rigorous adherence to the facts can allay fears and engender trust in the allocation process. Only by removing the pernicious influence of political machinations and entrenching the principles of fairness and equity can we hope to realize the full potential of grant-making to effect positive social change.

Thus, while the announcement of additional funding is indeed a positive development, it is crucial to tread carefully and ensure that all necessary steps are taken to avoid any potential pitfalls. Only then can we be certain that the interests of the most disadvantaged members of society are adequately safeguarded.

“…the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must”.

Thucydides – ‘The Peloponnesian War’, from the Melian Dialogue

Recent Comments