A deep dive into the August revolution in Bangladesh. And the ramifications and lessons at home in the East End of London.

Subaltern: Refers to those outside the hegemonic power structures, whose voices are often silenced or ignored in the dominant discourse.

In her influential essay “Can the Subaltern Speak?” Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak argued that subaltern groups are often so deeply marginalised that they cannot be heard within the dominant discourse, even when they attempt to speak.

Introduction: Continuation of the discussion at the Dhaka University, Fuller Road Residence.

This two-part analysis explores the August Revolution in Bangladesh and examines its possible repercussions in East London, colloquially known as ‘the Endz’. Part I delves into a theoretical framework underpinning the revolution, while Part II presents empirical evidence and chronicles the events leading to the upheaval of August 2024.

This written piece is dedicated to the memory of Professor Aftab Ahmed. In August 2006, during a lengthy evening discussion at his Dhaka University campus residence, he introduced me to the concept of a Bengali Muslim Subaltern.

The discussion began by examining the apparent animosity towards visible Islamic symbols within Dhaka’s upper echelons, particularly in academic settings. Recognising this tension, the professor urged his students to confront and question these attitudes. He generously opened his home and personal library as a sanctuary for his pupils to engage in open dialogue and conduct research on the subject.

Our intellectual journey that night commenced with Edward Said’s seminal work, “Orientalism,” which progressed through the writings of Ibn Khaldun, and culminated in an exploration of Ibn Taymiyyah’s teachings, in particular his critique of Greek Logic. Sadly, just a month after this enlightening session, in September 2006, Professor Ahmed’s life was cut short when he was murdered in the very home that had served as a haven for scholarly discourse.

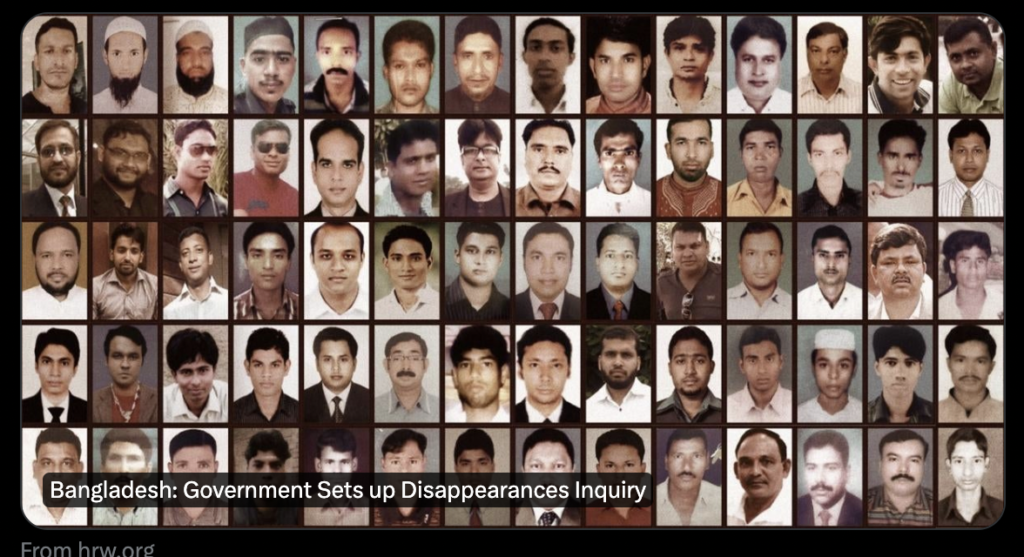

Following Professor Ahmed’s passing, the concept of the Bengal Subaltern persevered through the efforts of a small but dedicated group of intellectuals and activists. These individuals often faced significant opposition, including intense hostility and, in one extreme case, forced abduction by security services.

One prominent figure in this movement is Farhad Mazhar, whose wife, Farida Akhtar, now serves as a cabinet member in the post-August Revolution Government. Mazhar has gained fame within Bangladesh as an environmentalist and advocate for local farmers, particularly known for his campaigns against genetically modified crops promoted by multinational corporations. Internationally, he is recognized for his collaborations and associations with renowned intellectuals such as Gayatri Spivak and Jacques Derrida.

“The present political crisis is the result of the failure of the development policy and reducing the political process into an exercise of mere election. People are demanding the right to be heard, visible and participants in social, political and cultural processes that has been denied to them for the past 42 years.”

Farhad Mazhar, 9th May 2013

Mazhar leveraged his position, over the decades, as a public intellectual to speak out against institutional discrimination targeting marginalised groups that comprise the Bengal Subaltern. Through his persistent efforts, Mazhar has played a crucial role in maintaining the visibility and relevance of the Bengal Subaltern in the public discourse, despite facing considerable challenges from established power structures.

In the years since, I’ve had the opportunity to visit Bangladesh multiple times, engaging with a spectrum of individuals from ordinary citizens to key political and cultural figures, including Farhad Mazhar, both there and in the United Kingdom. These experiences have allowed me to gradually develop the ideas from that pivotal discussion into a cohesive framework. This framework aims to analyse and explain events in Bangladesh, and potentially forecast the nation’s trajectory.

Through this piece, instigated by the discussion with Professor Aftab Ahmed, I hope to offer a primer into the complex socio-political landscape of Bangladesh and its far-reaching implications, even in diaspora communities like East London.

It is a long-form piece divided into seven sections:

1. Nataraja: An Earthquake In Bangladesh, and the River of History Changes Course?

2. An Amodern Analysis: Latour, Ibn Khaldun and the Metaphysics of Identity

3. The Invention of Traditions: Bengal Renaissance vs The Bengal Subaltern

4. Defining the Asabiyyah of the Bengal Subaltern: A Bangla Vernacular Islamicate, Persianate or the Balkans to Bengal Complex?

5. Knowledge Triumphant: Modernity and the Uses of Literacy

6. Navigating the Bengal Subaltern: Various Currents in a Slow Moving River

7. Profane & Sacred Histories: Collapse of a Government or A Collapse of the Old Official National Identity?

1. Nataraja: An Earthquake In Bangladesh, and the River of History Changes Course?

“As he dances, the universe is created and destroyed, only to be reborn in his divine rhythm.”

Shiva Purana

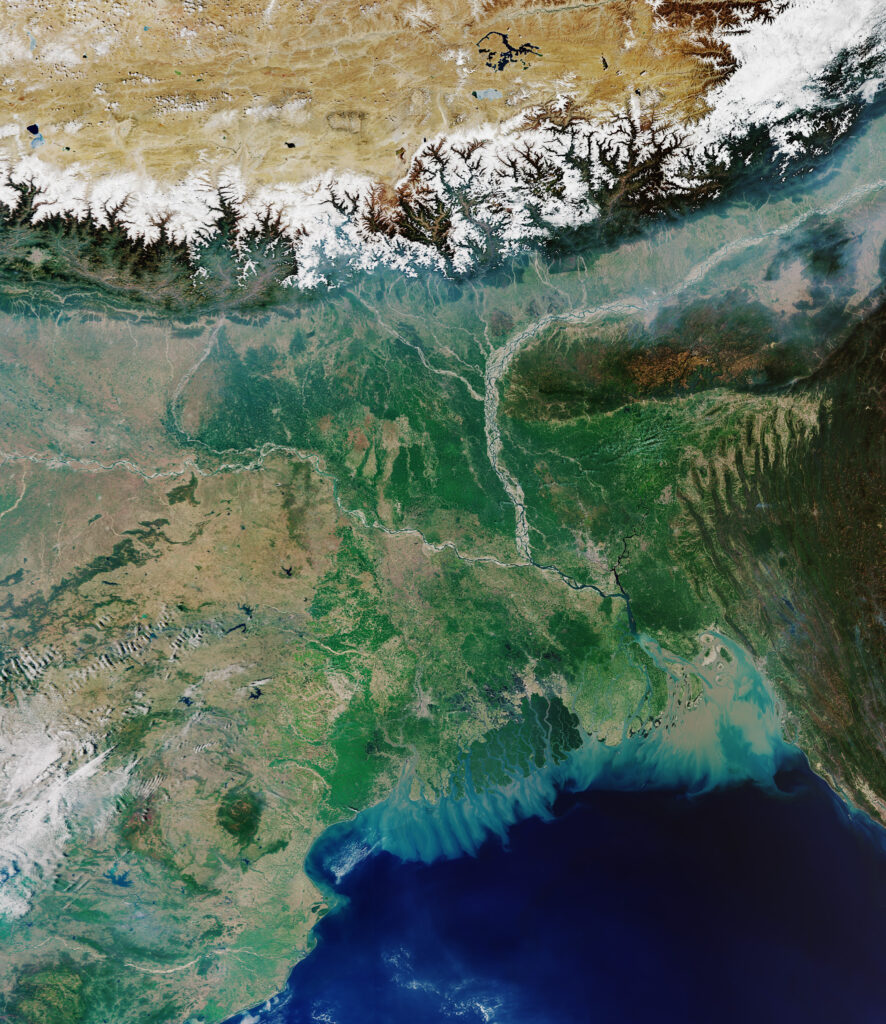

Bangladesh, a South Asian nation, is home to approximately 165 million people within its 147,570 square kilometres, making it one of the world’s most densely populated countries. Life expectancy is 72 years, and the literacy rate is 74%. However, it has one of the youngest populations in the world, with a median age of 27. The country sits at a geological crossroad where tectonic forces collide, where the continental shelf meets the Himalayan mountain range, making it prone to seismic activity. While small quakes are common, major earthquakes can have devastating effects, as outlined in the country’s history.

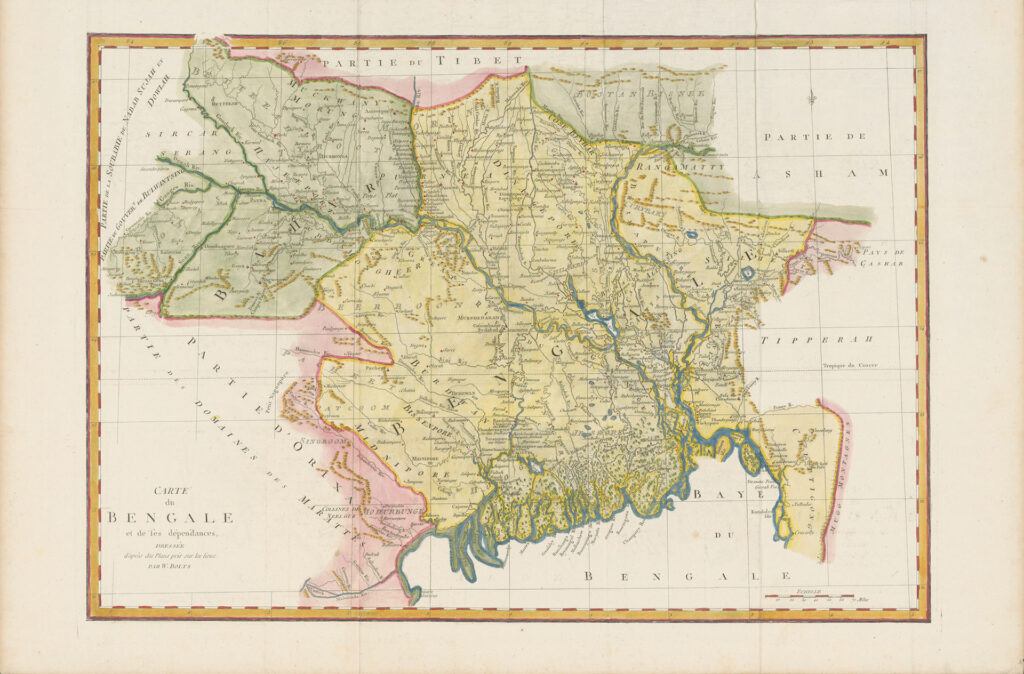

In 1762, five years after the epoch-changing victory of the East India Company, at Plassey, a powerful seismic event struck Bengal, causing such significant changes to the landscape that it altered the course of the mighty Brahmaputra River. Although the Brahmaputra River, joins the Ganges in Bangladesh, discharging into the Bay of Bengal. Its origins are at the foot of the Crystal Mountain, ‘Kailash’ along with the Sutlej River which flows into the Indus River in Pakistan. The source, in Tibet, is both revered by Buddhists and Hindus alike, for Hindus it is the place where Shiva danced and ordered the cosmos out of chaos into the world we inhabit today.

Fast-forward to August 2024, Bangladesh experienced another upheaval, a Nataraja, Dance of Shiva—this time, a political earthquake in the form of a street revolution. In a dramatic turn of events, the masses overthrew one government and welcomed another, led by Nobel laureate and economist Muhammad Yunus. This seismic shift’s impact reached East London, where demonstrators gathered in Altab Ali Park, celebrating the fall of Sheikh Hasina’s government. The revolution resonated in the UK media, even making it to the front page of the prestigious Economist magazine.

Rewind six months, and the headlines told a different story. This stable yet autocratic government had quashed all opposition through brute force and the systematic dismantling of democratic checks and balances. The Economist magazine even dubbed Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina as Asia’s longest-serving autocrat, labelling Bangladesh, as a one party state. This myopia raises more questions than it answers.

So how did seasoned Bangladesh watchers miss this tectonic shift? Since previous analytical frameworks failed to predict the revolution, is it not time for us to reassess these frameworks and adopt new ones?

Is the revolution in Bangladesh more than a change of government, but an overthrow of a narrative? Perhaps a new beginning for hitherto marginalised groups that make up the Bengal Subaltern?

2. An Amodern Analysis of Bangladesh: Latour, Ibn Khaldun and the Metaphysics of Identity

“Deep in the human unconscious is a pervasive need for a logical universe that makes sense. But the real universe is always one step beyond logic.”

Frank Herbert, Dune

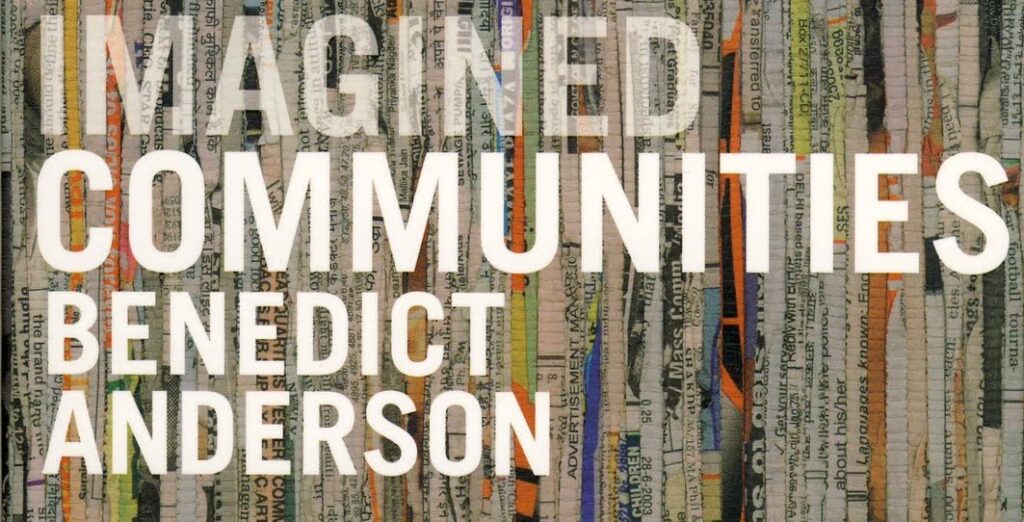

In 1991, French sociologist and philosopher Bruno Latour published his book “We Have Never Been Modern”, challenging the conventional understanding of modernity by arguing that it rests on a false premise— specifically, the rigid separation of subject and object. Instead, he offers shifting networks of relationships. Networks are not based on objective facts, but the result of complex negotiations and controversies, incorporating both human and non-human actors.

“We Have Never Been Modern” by Bruno Latour challenges the traditional distinction between nature and society, arguing that this separation is an artificial construct of modern thought.

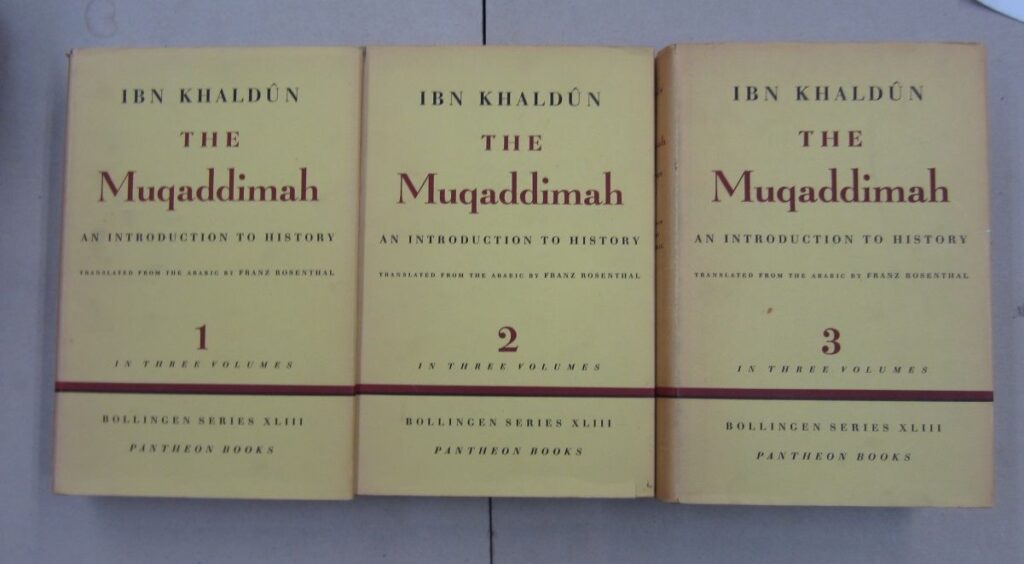

In the context of Bangladesh, anchoring these networks, as suggested by Professor Aftab Ahmed, we must turn to the 14th-century philosopher and historian Ibn Khaldun and his foundational concept of “Asabiyyah”. While often translated as “social cohesion,” a more fitting translation might be “Weltanschauung” or the metaphysics of group identity.

Ibn Khaldun’s Muqaddimah, or Introduction to History, suggests that the fundamental aspects of the human experience remain constant across time. Each generation must grapple with the same core questions that have shaped human identity and understanding throughout history: 1. Ontology: What is this world? 2. Cosmology: Where did it come from? 3. Epistemology: How do we know anything? 4. Soteriology: What do we do while we are here? 5. Eschatology: And finally, where are we going?

The answers to these questions form the foundation of a society’s collective identity, or Asabiyyah, as Ibn Khaldun terms it. This shared worldview is transmitted through informal social structures like family and kinship ties, as well as through formal education systems.

In his work on history, “The Muqaddimah”, Ibn Khaldun employs this framework to analyse historical events and the rise and fall of political entities. Moreover, he proposes that this model can be used to forecast future societal trends and occurrences, offering a tool for understanding both past and potential future developments in politics. Concluding, Ibn Khaldun argues that a stronger Asabiyyah can propel a group to conquer and overthrow an existing political order.

Ibn Khaldun’s ideas have resonated across time, influencing thinkers like Vico during the Enlightenment, Toynbee in the early 20th century, and even Frank Herbert’s “Dune” series in our postmodern era. To understand the recent revolution in Bangladesh, we need to delve into the dynamics of the collective identity of the Hasina government. Taking a leaf out of Edward Bernay’s ‘Propaganda’ enforced through controlled media and state institutions. On the other, the collective identity of the grassroots movement that eventually overthrew it. This requires a deep exploration of the motivations and group identities on both sides.

So what are these group identities?

3. The Invention of Traditions: The Bengal Renaissance vs The Bengal Subaltern

“It is the contrast between the constant change and innovation of the modern world and the attempt to structure at least some parts of social life within it as unchanging and invariant, that makes the ‘invention of tradition’ so interesting for historians of the past two centuries.”

Eric J. Hobsbawm, The Invention of Tradition

The roots of Bangladesh’s dual group identities can be traced back to the British colonial era, beginning with the East India Company’s (EIC) victory at the Battle of Plassey in 1757. Before this conquest, Bengal boasted a higher literacy rate than England itself. However, the East India Company’s subsequent actions drastically altered the region’s educational landscape.

The EIC systematically dismantled the endowments supporting local schools, profiting from their sale. This, coupled with the transformation of Bengal from a manufacturing hub into an extractive economy for raw materials, significantly reduced the need for an educated populace. As a result, the literacy rate plummeted to a mere 3.2%.

Economist and historian J.K. Galbraith highlighted the stark disparity in educational investment, noting that the education budget for the state of New York in the United States exceeded that allocated for the entirety of British India. By the time the British left in 1947, the literacy rate had only marginally improved to 16%, reflecting the limited concessions granted to local elites for access and participation in the colonial system.

This historical context helps explain the development of divergent group identities in what would later become Bangladesh, as access to education and opportunities became increasingly stratified during the colonial period. This led to the creation of divergent traditions and two identities coexisting within the same geographic entity.

On the one hand, you have the formation of the traditions of the mainly urban elite. The historical narrative of this period is dominated by the experiences of Bengal’s urban elites, who grappled with issues of modernity, state formation, and national identity through the Bengal Renaissance. This social, cultural, and intellectual movement spanned from the late 18th to the early 20th century, encompassing the regions of modern-day West Bengal and Bangladesh.

The Bengal Renaissance marked a period of profound transformation across various aspects of society. From literature, art and scientific thought to educational and social reforms. This movement was instrumental in shaping the elite traditions. A tradition firmly rooted in the European Enlightenment, and the adoption of its categories, though with Sanskritise Bengali characteristics.

یوں قتل سے بچّوں کے وہ بدنام نہ ہوتا

افسوس کے فرعون کو کالج کی نہ سُو جھی

‘Yun qatl se bachhon ke woh badnam na hota

Afsos ki Firaun ko college kee na soojhi’Pharaoh would’ve not earned the ill repute of being a murderer of children!

Akbar Allahabadi (1846 – 1921)

Had he just re-oriented the education to his own liking!

Then you have the experience of the vast majority, shut out from economic and educational opportunities provided by British colonialism. In the absence of access to the state-sanctioned high culture, the subaltern classes forged their own vibrant traditions, world views, and modes of self-expression. What Ibn Khaldun would call, Asabiyyah or collective group identity.

These alternative cultural forms became a means of resistance, resilience, and self-affirmation in the face of prolonged marginalisation. Sometimes these subaltern movements faced state violence from a combination of the state and economic actors, such as Titu Mir, who was killed and his movement suppressed through an alliance of landlords and the East India Company in 1831.

The divergent trajectories of the elite Bengal Renaissance and the Bengal Subaltern traditions of the rural poor laid the foundations for the deeply polarised group identities. A dual identity that continues to shape the social and cultural landscape of Bangladesh and its diaspora today.

So what filled the cultural and intellectual void left by the exclusion of the rural poor from the elite-driven Bengal Renaissance?

4. Defining the Asabiyyah of the Bengal Subaltern: A Bangla Vernacular of the Islamicate, Persianate or the Balkans to Bengal Complex?

“I am half-Muslim. I drink wine but don’t eat pork.”

Mirza Ghalib (1797–1869)

This phenomenon of dual collective identities is not unique to Bangladesh but is found in other Muslim countries, predominantly non-Arab and Eurasian. This led academics to debate the terminology for describing Asabiyyah, or group identities that emerged in these polities in the colonial and post-colonial eras.

Many academics, inspired by historian Marshall Hodgson, have adopted the term “Islamicate.” Hodgson introduced this concept to distinguish between the religious aspects of Islam and the broader cultural elements of societies influenced by Islamic civilization.

Marshall Hodgson, renowned for his work on the history of Islamic civilisation and its global context. Born in 1922 and passing away in 1968, Hodgson is best known for his influential three-volume work, ‘The Venture of Islam.’ Hodgson’s work is highly regarded for its analytical depth and its attempt to situate Islamic history within a broader global framework.

Hodgeson’s Islamicate transcends the strictly religious bounds of Islam while sharing its metaphysical foundation. This concept encompasses cultural elements adopted by Muslim groups and individuals, as well as non-Muslims extending beyond purely Islamic practices.

Hodgson introduced the Persianate as a subcategory within the Islamicate, describing a shared cultural landscape that existed before European colonialism. This Persianate sphere stretched from the Balkans and Russia through Turkey, reaching as far as India and Bengal.

“The rise of Persian had more than purely literary consequences: it served to carry a new overall cultural orientation within Islamdom…. Most of the more local languages of high culture that later emerged among Muslims… depended upon Persian wholly or in part for their prime literary inspiration. We may call all these cultural traditions, carried in Persian or reflecting Persian inspiration, ‘Persianate’ by extension.”

Marshall Hodegson – The Venture of Islam: The expansion of Islam in the Middle Periods

Shahab Ahmed was a distinguished scholar of Islamic studies, known for his groundbreaking work on Islamic intellectual history and culture. Born in Singapore in 1966, he pursued his education in the United Kingdom and the United States, earning his Ph.D. from Princeton University. He held academic positions at Harvard University and the American University in Cairo. He passed away in 2015.

In his book “What is Islam?”, Shahab Ahmed offers a critique of Marshall Hodgson’s definition of the Islamicate, proposing instead a more nuanced understanding. He terms it as the “Balkans to Bengal Complex”. Ahmed characterises it as a “hermeneutical engagement,” emphasising its nature as an ongoing process of interpretation and meaning-making. In this context, Asabiyyah can be understood as the outcome of an individual’s continuous interaction with their traditions, texts, and surrounding world, leading to a diverse spectrum of interpretations and practices.

In terms of the impact on the Indian Subcontinent, Richard Eaton’s “India in the Persianate Age: 1000–1765” challenges Eurocentric views of pre-colonial India by examining the profound impact of Persianate culture on the subcontinent. Before British arrival, this cultural framework significantly shaped the region’s history and group identities in many areas, under the Delhi Sultanate and Mughal Empire.

For seven centuries, a dynamic cultural exchange unfolded in the Indian Subcontinent, shaping what Richard Eaton describes as an “Indo-Persian culture.” This framework, far from being exclusive or imposed, invited participation from both Muslims and non-Muslims alike. Eaton emphasises the reciprocal nature of this interaction, which profoundly influenced all participants regardless of their religious background. His analysis reveals a nuanced, multi-layered process of cultural synthesis, challenging overly simplistic views of cultural domination or assimilation.

A good example of this cultural synthesis is the interaction between Sufis and Hidu holy men. According to Eaton, the fusion of Islamic and Hindu spiritual ideas contributed to the development of syncretic practices and devotional movements like Bhakti. This perspective offers a more complex understanding of the region’s rich cultural tapestry, woven through centuries of mutual exchange and adaptation.

Once a dominant group identity, this Asabiyyah was suppressed by British colonial authorities and later marginalised by postcolonial institutions. Instead of fading into obscurity, it adapted to become part of the Bengal subaltern culture. By embracing vernacular forms and adjusting to modern circumstances, it has managed to persist. Consistently challenging Bangladesh’s official narrative and elite-driven identity, rooted in the Bengal Renaissance, offering an alternative perspective from below.

Not spoken of nor given a voice, the Bengal Subaltern is overlooked in the official narrative. However, it is seen and heard throughout the country. What Ahmed describes as the ‘Balkan to Bengal Complex’ or Eaton and Hodgeson describe as the Persiante influences permeate Bangladesh’s cultural landscape. Seamlessly blending with local traditions, to form the Bengal Subaltern.

Who’s national instrument is it anyway or a Persianate shared national instrument? Left: Dotara being played in Samarkand, Uzbekistan. Right: Dotara is celebrated on a stamp in Bangladesh.

In bustling bazaars across the country, aromas of biryani and kebabs mingle with the sweet scent of halwa, all testament to a Persianate culinary heritage. The very language of commerce in these markets—a vibrant mix of Arabic, and Persian, fused with local Bengali dialects. In some places, as night falls and market stalls shutter, the bazaar’s atmosphere transforms. Folk musicians emerge, their melodies carried by the Ektara and Dotara—instruments with Persianate lineage. These artists often perform Ghazals, a poetic form deeply rooted in a Persianate tradition. Their songs, rich with themes of love and longing, draw motifs and inspiration from timeless Persianate narratives like Jami’s “Yusuf and Zulaika” or Rumi’s “Layla and Majnun.”

Given the opposition from powerful state institutions and economic elites, how does the Bengal Subaltern manage to persist and thrive?

Richard M. Eaton’s book “The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204-1760”, challenges the traditional narrative of Islam spreading through military conquest, instead presenting it as a gradual and region-specific process driven by cultural and economic factors. His work highlights the importance of the agrarian frontier in shaping Bengal’s Islamic identity and has significantly influenced the understanding of South Asian history.

5. Knowledge Triumphant: Modernity and the Uses of Literacy

“The man who has knowledge is considered most outstanding among people, Even if he does not occupy a position of nobility among his people. Wherever he settles, he can make a living from his knowledge. A man who possesses knowledge is no stranger anywhere.”

Franz Rosenthal, Knowledge Triumphant: The Concept of Knowledge in Medieval Islam

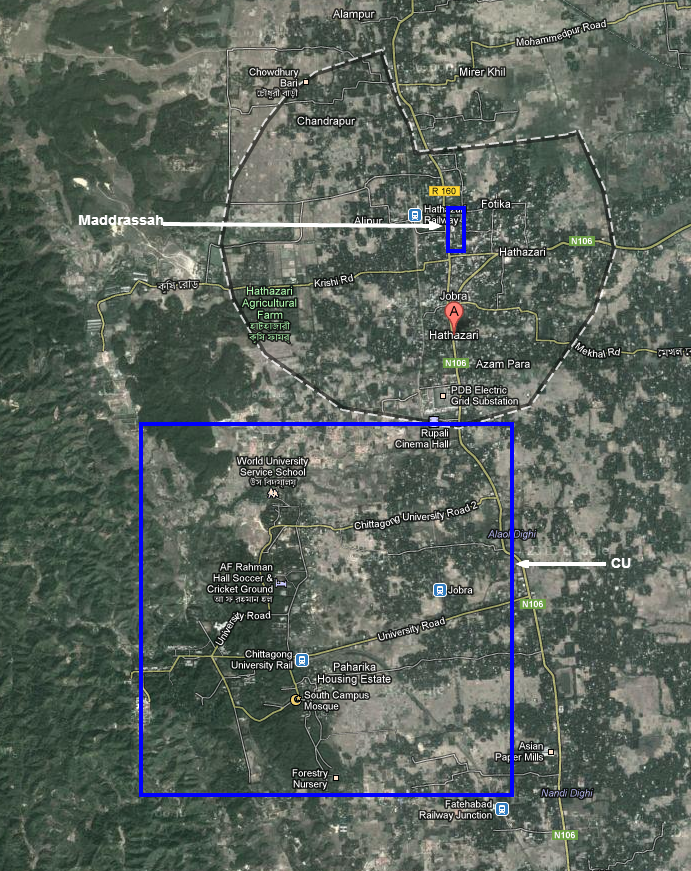

The region of Hathazari, located near the port city of Chittagong, serves as a compelling case study for understanding the formation of the Bengal Subaltern in modern-day Bangladesh. This area sits at the end of the historic Mughal Grand Trunk Road, which stretches from Peshawar and the Khyber Pass, winding its way through major cities like Lahore, Delhi, Lucknow, and Dhaka, before terminating in Chittagong.

The region is dotted with Sufi shrines, the most famous being Shah Amanat and Syed Bostami. A few kilometers away stands the private International Islamic University of Chittagong, established by members of the Islamist group Jamaat-e-Islami. Both of these groups have influenced the Bengal subaltern.

However, at the centre of Hathazari is a seminary, which I believe has had the most influence, in terms of high impact, in the area. This is the Al-Jamiah al-Ahliyyah Dr al-Ulm Muin al-Islam, also known as the Hathazari Madrasah. This Deobandi madrasa, the oldest in Bangladesh, was founded in 1901 and currently serves over 50,000 students. This is remarkable considering the nearby University of Chittagong, which serves only 20,000 students despite occupying a land area fifty times larger. Hathazari is one of tens of thousands of seminaries throughout Bangladesh, outnumbering the number of private and public universities, meeting the demand for literacy unmet by the state.

Outside the purview of the elites, the visual, economic, and cultural fabric of Bangladesh has been developing in a manner that contrasts with the culture propagated by the upper classes. Islamic banks and Sharia-based financial systems have proliferated in provincial towns. A myriad of Islamic learning institutions, ranging from supplementary schools to full-fledged colleges and universities, have stepped in to fill the gap left by the state, throughout the country. This contributed to the advance of literacy rates in the country to 74%, from 16% at the end of the British Raj in 1947.

The most visible example of this Subaltern Bengal is the annual Bishwa Ijtema in Dhaka – the largest gathering of Muslims outside of the Hajj pilgrimage. Attended by millions, many travelling long distances from rural areas to the capital, this event draws significant attention. Recognising the optics and influence of this massive gathering, all major political parties send representatives to be present. This event, organised by the non-state actor Tabligh Jamaat using its extensive grassroots networks, highlights the power and reach of the Subaltern cultural forces in Bangladesh.

Therefore, modern Bangladesh becomes a paradox with two competing cultural forces and identities, uneasily sitting side by side, like two mighty rivers, with different headwaters flowing into the same estuary. Does that mean Bangladesh was in a state of a forever culture war?

6. Navigating the Bengal Subaltern: Various Currents in a Slow Moving River

The answer is no. The Bengal Subaltern is not a hegemonic force vying for political power or seeking to capture governmental institutions. Instead, it functions as a network addressing the needs of those left behind economically, educationally, and culturally by the state. Creating a space for people to voice and make meaning of the traditions they grew up with.

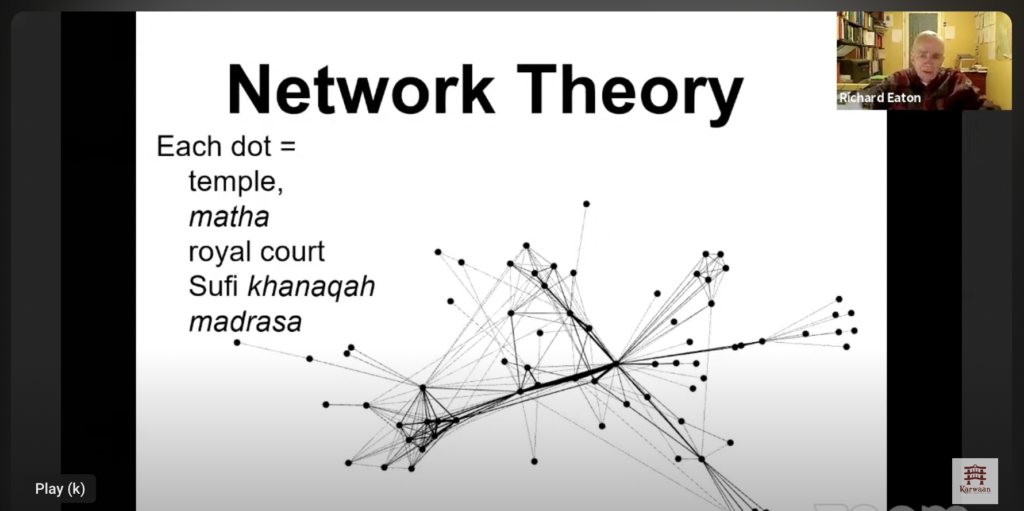

Bruno Latour’s Actor-Network Theory (ANT) provides a useful theoretical framework for understanding the Asabiyyah (group solidarity) of the Bengal Subaltern. Through this lens, the Bengal Subaltern emerges not as a singular movement or institution, but as a complex network of relationships between groups and individuals striving to create meaning in a dynamic world. The historian Richard Eaton uses a derivation of the theory when describing the interconnectedness of India during the Persianate Age.

The Bengal Subaltern encompasses a wide range of interpretations and apparent contradictions, maintaining a shared Asabiyyah or group identity. For instance, certain practices in Sufi shrines might seem at odds with the legalism taught in seminaries, yet they coexist. For example, the Shahjalal shrine in Sylhet, which houses a Deobandi seminary within its complex, exemplifies this coexistence.

Latour’s theory gives us insights into the role of non-human actors in shaping the Asabiyyah of the Bengal Subaltern. In Bangladesh, factors such as high population density, living with the impact of monsoon floods, and the communal nature of rice cultivation foster a culture of tolerance. This has led to the peaceful coexistence of different Asabiyyahs or group identities in modern-day Bangladesh. A good example is the Deobandi Seminary in rural, Sylhet, which houses a Hindu Temple within its grounds. Every year, students and teachers vacate the premises, allowing Hindus to celebrate the birth of a god at the temple.

So what led to the collapse of this coexistence?

“Laboratory Life: The Construction of Scientific Facts” is a seminal book by Bruno Latour and Steve Woolgar, first published in 1979. It laid the groundwork for what would later become Actor-Network Theory, a framework that Latour developed to analyse the relationships between humans, technology, and natural phenomena in the production of knowledge.

7. Profane & Sacred Histories: Collapse of a Government or A Collapse of the Old Official National Identity?

Cosmos and History: The Myth of the Eternal Return by Mircea Eliade. A seminal work in the field of religious studies and comparative mythology. Published in 1959, the book explores the idea that ancient and traditional societies perceived time and history in fundamentally different ways compared to modern, secular perspectives.

“Light does not come from light, but from darkness.”

Mircea Eliade

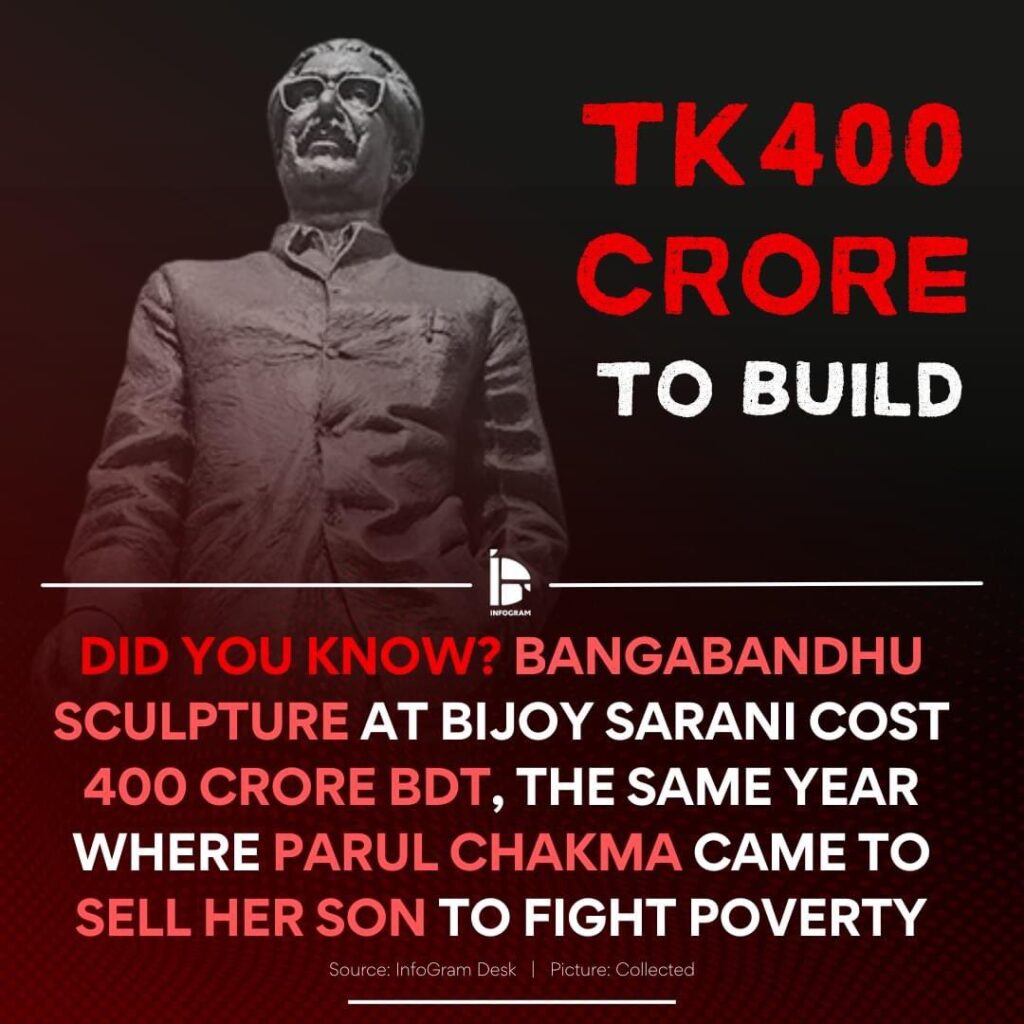

The period from 2009 to 2024, under Sheikh Hasina’s government, saw a gradual erosion of the previously established coexistence. A combination of external pressures and the government’s missteps led to a widespread loss of faith in the official vision of Bangladesh that had been promoted. The events of August 2024 did not just result in the government’s downfall, but also in the collapse of the national narrative that had been cultivated, by Hasina’s Awami League Party since Bangladesh’s independence in 1971.

In the aftermath of what became known as the August Revolution, symbols of the old order, such as statues of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, were removed, and official observances like the holiday marking his death were discontinued. Collective acts not only mark the demise of a government but also a change in the course of the country of Bangladesh.

“The ceaseless practice of class and cultural difference has constantly brutalised the feelings and the sense of social exclusion by the large majority of the population, who are already economically deprived, exploited and forced to survive outside the perimeter of law and justice by a lopsided developmental model.“

Farhad Mazhar, 9th May 2013

The Romanian historian and religious scholar Mircea Eliade, were he alive today, would likely interpret the August Revolution in Bangladesh through his distinctive philosophical lens. Rather than viewing it as an isolated historical event to be understood solely within its immediate context, Eliade might have approached it as part of a broader, archetypal pattern that transcends linear time.

In Eliade’s perspective, the revolution could be seen as an embodiment of cyclical mythic structures deeply rooted in local traditions. Drawing parallels between the revolution and the concept of eternal return, suggesting that it represented a moment of cosmic renewal. He might have interpreted it as part of a grand cycle of creation, preservation, and destruction – akin to the dance of Nataraja in Hindu mythology – followed by rebirth and a new beginning.

As one cycle ends, so another one begins. Following the August Revolution, in an (un)expected turn of events, Muhammad Yunus, the Nobel Laureate known as ‘The Banker to the Poor,’ was asked to assume leadership of the new government. His ascension seems predestined, given his origin, career path and now, trajectory.

Yunus hails from Hathazari, a place that epitomises the Bengal Subaltern experience, near the terminus of the historic Mughal Grand Trunk Road. Dotted with Sufi shrines and overlooked by its Boro Madarsah, or ‘Great Seminary’. It was while teaching economics at the nearby University of Chittagong that he conducted his groundbreaking fieldwork in microcredit among the local villages. Now as Chief Adviser to the Government of Bangladesh, he attempts to plot a new course.

Or, as the Arabic proverb aptly states, “Everything returns to its origins.”

Part II will examine the events and factors contributing to the downfall of Sheikh Hasina’s government and the erosion of the group identity it fostered. This section will also analyse how these developments reverberated through the Bangladeshi diaspora community in East London.

Further Reading

Readings of the Bengal Subalatern

In addition to the books referenced above and in the images:

History of The Muslims of Bengal by Professor Muhammad Mohor Ali

Readings of the Bengal Renaissance:

Exploring the Bengal Renaissance: The “Other” Alternative South Asian Heritage?

Brilliant synthesis. Specially liked this: “. The Bengal Subaltern is not a hegemonic force vying for political power or seeking to capture governmental institutions. Instead, it functions as a network addressing the needs of those left behind economically, educationally, and culturally by the state. Creating a space for people to voice and make meaning of the traditions they grew up with.’