Are you interested in delving into the intricate relationship between politics and the lack of social infrastructure in Tower Hamlets? Or where £6 million earmarked for physical infrastructure has gone?

Join us as we unveil the hidden truths behind Tower Hamlets’ political landscape and its impact on the crumbling state of its infrastructure.

“Much of life for many people, even in the heart of the First World, still consists of waiting in a bus shelter with your shopping for a bus that never comes.”

Doreen Massey

Introducing the Tower Hamlets Paradox: Disparities Persist Despite Infrastructure Investment

The London Borough of Tower Hamlets stands as a stark testament to the persisting inequalities within the United Kingdom and, indeed, Western Europe. With per capita income soaring well beyond the £120,000 mark, this borough has emerged as a microcosm of the profound economic disparities that plague our societies. A closer examination reveals that the soaring wealth can be attributed to substantial investments made in the region since the 1980s, most notably exemplified by the thriving financial hub, Canary Wharf, and the advent of the Docklands Light Railway. The most recent addition to this urban rejuvenation is the newly established Whitechapel station, catering to the Elizabeth Line.

Economic theory has long espoused the notion that infrastructure investment plays a pivotal role in fostering social inclusion. By establishing vital links within marginalised communities, such investments bolster accessibility to essential services and work towards reducing inequalities. They strive to ensure that citizens from all walks of life, irrespective of their socio-economic backgrounds, are bestowed with equitable opportunities and unimpeded access to fundamental amenities, education, healthcare, and employment prospects. Furthermore, robust infrastructure acts as a magnet for industries stimulates productivity, and generates employment possibilities, thereby contributing to the overall growth of an economy. It is an indispensable component in the pursuit of prosperous and sustainable societies.

However, amidst the towering edifices and bustling economic activity, a disconcerting reality persists. Astonishingly, more than half of the households in Tower Hamlets that house children suffer from food poverty. A term that encapsulates the woeful inability of individuals or households to procure sufficient nutritious sustenance due to meagre incomes, elevated living costs, and inadequate social welfare support. This predicament has metamorphosed into a pressing concern, necessitating an alarming reliance on food banks and philanthropic assistance. The pernicious consequences of food poverty, extending beyond the physical realm, also encroach upon mental well-being. In response, concerted efforts have been initiated, including the establishment of food banks, school meal programs, and awareness campaigns, all aiming to confront this multifaceted predicament.

The deleterious ramifications of food poverty have been manifested in the form of pronounced health inequalities, a sobering reality that has prompted the Tower Hamlets Council, in the last year, to undertake corrective measures. To address this issue, the council has taken the laudable step of implementing free universal school meals and augmenting funding for food banks. Despite these earnest endeavours, a pertinent question begs to be answered: What has obstructed the allocation of funds for infrastructure improvements under planning gains, and why have such endeavours not yielded the anticipated impact? Before delving into an exploration of these critical queries. It is imperative to gain a comprehensive understanding of the financial resources at the disposal of the Tower Hamlets Council, as they endeavour to uplift the infrastructure and subsequently enhance the lives of its residents.

What are the monies available?: Tower Hamlets’ Development Boom Raises Questions on Community Benefits.

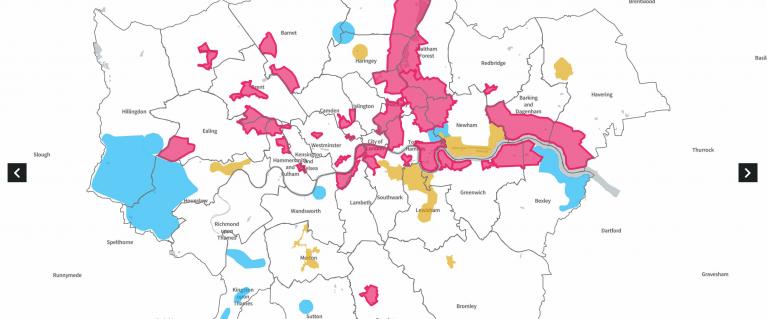

Tower Hamlets and Newham, two prominent London boroughs, have experienced a surge in development in recent years, at one time with an astonishing 50% of all new developments in London, concentrated within their borders. This unprecedented level of growth, exemplified by Newham’s role as the host of the Olympics, provides insight into the magnitude of development witnessed in Tower Hamlets. Remarkably, this pace of development persists, as Tower Hamlets boasts the highest number of Opportunity Areas in the capital.

In the realm of London’s planning and development landscape, Opportunity Areas are designated regions deemed to possess significant potential for transformation and growth. These areas are carefully identified by the Mayor of London and local authorities as locations where substantial enhancements can be made in terms of the economy, society, and the environment.

Opportunity Areas serve as focal points, concentrating resources, policies, and planning efforts to unlock their inherent potential and maximize their contribution to London’s overall expansion. The objectives encompass a wide range of endeavours, including the creation of new residential properties, employment opportunities, improved transportation systems, public spaces, and community amenities. By concentrating efforts in these areas, Opportunity Areas play an integral role in London’s strategic planning framework, guiding the city’s growth in a coordinated and sustainable manner.

However, despite the substantial influx of development and the associated financial resources pouring into the coffers of Tower Hamlets Council, it is disheartening to observe that the local populace has not reaped the anticipated benefits. In fact, the available data from Tower Hamlets indicates that conditions have deteriorated, raising important questions about the allocation and effectiveness of the received funds.

It is crucial to acknowledge that the financial resources generated through the Community Infrastructure Levy (CIL) and Section 106 agreements are mechanisms employed by local authorities in the UK to secure contributions from developers for infrastructure improvements and community benefits. While CIL represents a standardized charge applicable to most developments, Section 106 agreements are individually negotiated, allowing for customized obligations to address the specific impacts of each project.

The Community Infrastructure Levy (CIL) is a charge imposed by UK local authorities on new developments to fund infrastructure projects. It is calculated based on factors like the size and type of the development. The money collected through CIL is used to support the infrastructure needs of growing communities resulting from new developments, including roads, schools, healthcare facilities, parks, and community centres. Local authorities have flexibility in allocating and spending CIL funds, following consultation with the local community and stakeholders.

Section 106 agreements, also known as planning obligations in the UK, are legal agreements between local authorities and developers as part of the planning permission process. These agreements aim to mitigate the impact of new developments by securing financial contributions or other obligations from developers. These contributions, known as Section 106 monies, are negotiated on a case-by-case basis and can be used for various purposes such as affordable housing, education, transportation, open spaces, and healthcare. Section 106 agreements are legally binding and serve to ensure that developers contribute to the necessary infrastructure and community benefits associated with their projects.

While CIL is a standardized charge applied to most developments, Section 106 agreements are negotiated on a case-by-case basis, allowing for more tailored obligations to address the specific impacts of a particular development. Hence, given the scale of developments and the significant financial resources flowing into the coffers of Tower Hamlets Council, it is essential to investigate why the local population has not experienced the expected benefits. The available data suggest that the situation has actually worsened, necessitating a deeper examination of the factors contributing to this outcome.

Dude, where has all the money gone? #£6MillionMissing

In examining the financial details, it is instructive to first explore a tangible illustration, namely the City Fringe Opportunity Area, situated west of Tower Hamlets and encompassing the Weavers, Spitalfields & Banglatown, and Whitechapel wards. Despite assertions of improved infrastructure resulting from escalated development, the area’s residents have not reaped the benefits. Notably, there has been a decline in households with children, exemplified by the closure of one primary school and the precarious situation of two others. Conversations with locals indicate a paucity of public spaces catering to women and children, with a visible reduction observed in the Brick Lane vicinity.

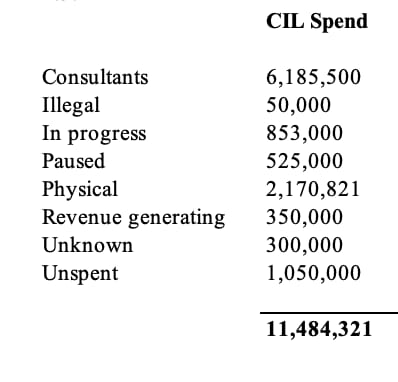

Thus arises the question: why have the funds derived from the area’s new developments not been allocated towards social infrastructure? Scrutiny conducted by Andrew Wood, the former Councillor for Canary Wharf, has exposed a disconcerting reality: the lion’s share of the financial allocation intended for physical infrastructure has been expended on “consultants.”

Collaborating with dedicated community members, I embarked on an extensive investigation into Tower Hamlets Council’s official financial records. This meticulous inquiry sought to ascertain the specific disbursements, beneficiaries, amounts, and timeframes involved. The examined period spanned from 2019 to 2023, with the majority of transactions authorized during the prior mayoral tenure of John Biggs, of the Labour Party. In total, if you include the now-discredited Liveable Streets scheme, this gives us a total of £10 million to consultants. To put things into perspective, that is the approximate total cost to feed every single school child in Tower Hamlets for 5 years.

| Total spend by Tower Hamlets Council (all), presumption from s106 monies including CIL | THCIL Consultants | Total CIL | 2019/20 | 2020/21 | 2021/22 | 2022/23 |

| £1,521,486.57 | Arcadis Consulting (UK) Ltd | £1,453,033.61 | £345,696.75 | £251,080.97 | £286,732.16 | £569,523.73 |

| £97,950.00 | Norman Rourke Pryme Ltd | £67,950.00 | £0.00 | £0.00 | £16,000.00 | £51,950.00 |

| £70,000.00 | THREEDAY GROUP LTD | £57,850.00 | £0.00 | £0.00 | £0.00 | £57,850.00 |

| £88,850.00 | Montagu Evans LLP | £38,950.00 | £0.00 | £33,700.00 | £5,250.00 | £0.00 |

| £34,838.25 | LDA Design Consulting LLP | £34,838.25 | £0.00 | £0.00 | £34,838.25 | £0.00 |

| £898,423.00 | J&L Coster (Drainage) Ltd | £30,050.00 | £0.00 | £0.00 | £30,050.00 | £0.00 |

| £24,530.28 | Ardent Management Limited | £24,530.28 | £24,530.28 | £0.00 | £0.00 | £0.00 |

| £24,290.00 | Applied Wayfinding | £24,290.00 | £0.00 | £22,398.60 | £1,891.40 | £0.00 |

| £75,448.65 | Beckett Rankine Marine Consulting Engineers | £23,587.50 | £0.00 | £0.00 | £0.00 | £23,587.50 |

| £1,035,840.31 | Face Events LTD | £23,500.00 | £0.00 | £0.00 | £23,500.00 | £0.00 |

| £90,990.00 | Knight Architects Limited | £22,000.00 | £0.00 | £22,000.00 | £0.00 | £0.00 |

| £21,070.00 | Colliers International Property Advisers UK LLP | £21,070.00 | £0.00 | £0.00 | £21,070.00 | £0.00 |

| £18,750.00 | Phar Partnerships Ltd | £18,750.00 | £18,750.00 | £0.00 | £0.00 | £0.00 |

| £18,100.00 | Frame Projects Ltd | £18,100.00 | £0.00 | £0.00 | £18,100.00 | £0.00 |

| £150,156.82 | Steer Davies Gleave | £18,000.00 | £0.00 | £0.00 | £0.00 | £18,000.00 |

| £762,428.59 | One Consulting Group | £16,500.00 | £0.00 | £0.00 | £0.00 | £16,500.00 |

| £120,870.07 | Sharpe Pritchard | £8,652.00 | £7,596.00 | £0.00 | £1,056.00 | £0.00 |

| £9,400.00 | Open City Architecture | £5,000.00 | £0.00 | £0.00 | £5,000.00 | £0.00 |

| £258,983.34 | GERALD EVE LLP | £5,000.00 | £0.00 | £5,000.00 | £0.00 | £0.00 |

| £2,700.00 | Social Broadcasts Ltd | £2,700.00 | £0.00 | £0.00 | £1,800.00 | £900.00 |

| £33,908.60 | Docklands Light Railway Limited | £2,218.50 | £0.00 | £0.00 | £0.00 | £2,218.50 |

| £1,800.00 | Europa | £1,800.00 | £0.00 | £0.00 | £0.00 | £1,800.00 |

| £700.00 | Fieldnotes | £700.00 | £0.00 | £0.00 | £700.00 | £0.00 |

| £500.00 | Massey Maddison Limited | £500.00 | £0.00 | £500.00 | £0.00 | £0.00 |

| £500.00 | Benedict O’Looney Architects | £500.00 | £0.00 | £0.00 | £0.00 | £500.00 |

| £474,050.89 | TMP UK Ltd | £401.00 | £0.00 | £401.00 | £0.00 | £0.00 |

| £0.00 | £0.00 | £0.00 | £0.00 | £0.00 | £0.00 | |

| £5,836,565.37 | £1,920,471.14 | £396,573.03 | £335,080.57 | £445,987.81 | £742,829.73 |

Ways Forward: A new set of financial modelling?

Setting aside the pertinent legal concerns surrounding value-for-money obligations tied to Tower Hamlets Council and its former political leadership, a profound structural quandary looms over the council’s approach to infrastructure investments. During my tenure as a councillor, spanning from 2018 to 2022, the absence of open deliberations regarding transparent evaluation criteria for such investments became evident. Instead of relying on sound scientific analysis, decision-making often leaned towards a more nebulous and whimsical process, fixated on expenditure amounts rather than tangible outcomes. This tendency may partially elucidate the council’s overdependence on consultants to validate such financial outlays, which, regrettably, fosters ongoing discussions by the Tower Hamlets Labour Group revolving around spending quantum, rather than the unambiguous benefits yielded by these investments.

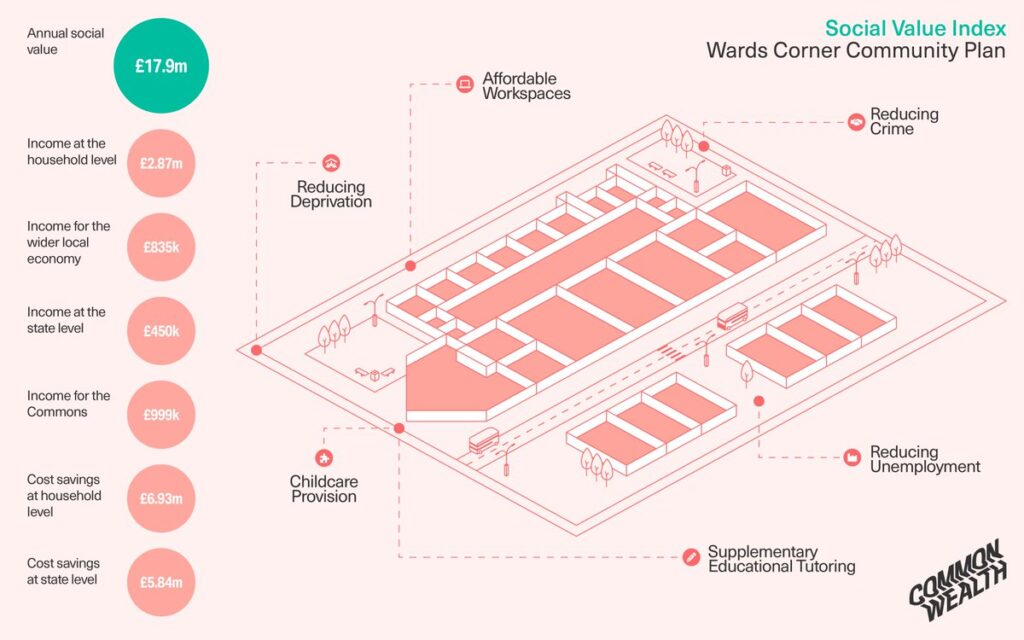

Of particular concern is the lack of strategic direction guiding these investments. Given that the private sector influx, exemplified by novel developments, tends to prioritize bolstering productivity, an unintended by-product emerges a deepening of societal inequalities. In light of this observation, one may reasonably question whether public sector investments, specifically those directed towards social infrastructure, should pivot their focus towards mitigating these disparities.

In a noteworthy display of leadership, Haringey Council, under Labour’s stewardship, has spearheaded progress in this realm. The council astutely commissioned the Common Wealth think tank to devise comprehensive financial models that assess and audit social infrastructure, ‘A Social Value Index’. This approach empowers decision-makers with the tools to make transparent and well-informed judgments pertaining to public infrastructure investments. By instigating a framework that promotes genuine public discourse, as opposed to the insular, clandestine, and exorbitant realm of “consultant’s reports,” Haringey Council has set a commendable precedent.

Applying Doreen Massey in the 21st Century.

Doreen Massey, the esteemed British geographer (1944-2016), left an indelible mark on the field of human geography with her groundbreaking contributions. Renowned for her incisive spatial theory, regional development insights, and unwavering commitment to social justice, Massey’s intellectual legacy continues to reverberate.

Central to Massey’s oeuvre was her conviction that space cannot be divorced from power dynamics; rather, it is irrevocably shaped by them. By illuminating the spatial dimensions of inequality, Massey emphasized the imperative of comprehending space as an inherently non-neutral entity. Her magnum opus, “Space, Place, and Gender” (1994), delved into the intricate interplay between gender, space, and social power, shedding light on the manifold ways in which these factors intersect.

Moreover, Massey directed her scholarly gaze towards the dynamics of global cities, propounding a vision of urban and regional development that championed inclusivity and democracy. Her seminal work, “World City” (2007), advocated for an approach that embraced the diverse populace and fostered an egalitarian society. Throughout her illustrious career, Massey emerged as a resolute advocate for social justice, continually espousing the cause of equality.

Indeed, Massey’s profound insights reverberate far beyond the realm of geography. They resonate with policymakers, planners, and discerning individuals eager to create a fairer, more equitable society. As we engage in transparent financial modelling, we find fertile ground for the application of Massey’s ideas. By dismantling entrenched power relations within the built environment and spatial configuration, we possess the opportunity to mitigate the entrenched inequalities plaguing locales such as Tower Hamlets.

Our paramount objective lies in ensuring that the benefits of public investment in infrastructure cascade to ordinary residents and their families. Gone should be the era where a select few, draped in the ambiguous titles of ‘consultants’ and ‘friends of consultants,’ disproportionately reap the rewards. Instead, Massey’s legacy beckons us to foster a transformative vision that nurtures inclusivity and empowers marginalized communities.

In embracing Massey’s paradigm, we embark on a journey towards a more just and egalitarian society, where power is democratically diffused, and opportunities are genuinely accessible to all. By leveraging her profound understanding of power, space, and social relations, we can forge a path that leads us away from the prevailing quagmire of inequality, towards a future imbued with fairness and prosperity.

“If time is the dimension of change, then space is the dimension of coexisting difference. And that is both a source of nourishment (something that the globalisation gurus seem altogether to have foregone), and a challenge (how negotiate difference, how to address inequality, and so forth).”

Doreen Massey

Further Reading

- Massey, D. B. (1994), Space, place, and gender. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press

- Massey, D. B. (1995), Spatial divisions of labor: Social structures and the geography of production, 2nd edition. New York: Routledge.

- Massey, D. B. (2010), World City, with new Preface: “After the Crash”, July 2010. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Recent Comments